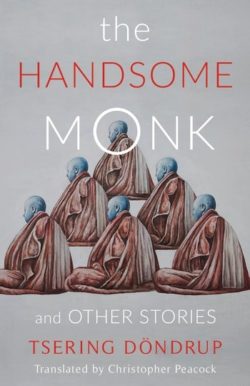

The Handsome Monk, by Tsering Döndrup

translated by Christopher Peacock

Columbia University Press, 2019

Publisher's blurb

Tsering Döndrup is one of the most popular and critically acclaimed authors writing in Tibetan today. In a distinct voice rich in black humor and irony, he describes the lives of Tibetans in contemporary China with wit, empathy, and a passionate sense of  justice. The Handsome Monk and Other Stories brings together short stories from across Tsering Döndrup’s career to create a panorama of Tibetan society.

justice. The Handsome Monk and Other Stories brings together short stories from across Tsering Döndrup’s career to create a panorama of Tibetan society.

With a love for the sparse yet vivid language of traditional Tibetan life, Tsering Döndrup tells tales of hypocritical lamas, crooked officials, violent conflicts, and loyal yaks. His nomad characters find themselves in scenarios that are at once strange and familiar, satirical yet poignant. The stories are set in the fictional county of Tsezhung, where Tsering Döndrup’s characters live their lives against the striking backdrop of Tibet’s natural landscape and go about their daily business to the ever-present rhythms of Tibetan religious life. Tsering Döndrup confronts pressing issues: the corruption of religious institutions; the indignities and injustices of Chinese rule; poverty and social ills such as gambling and alcoholism; and the hardships of a minority group struggling to maintain its identity in the face of overwhelming odds. Ranging in style from playful updates of traditional storytelling techniques to narrative experimentation, Tsering Döndrup’s tales pay tribute to the resilience of Tibetan culture.

Reading Chinese Network Reviews

Reviewed by Bing Wang, 7/4/20

For someone who has never been to Tibet like me, The Handsome Monk and Other Stories by TSERING DÖNDRUP is a satisfactory read. Thanks to Christopher Peacock’s translation, it becomes a reality for us non-Tibetan speakers to have a taste of genuine Tibetan culture. This perfect translation does not deprive the Tibetan essence from TSERING DÖNDRUP’s writings. By contrast, it justifies how witty the author is in mastering humour in his writing.

For someone who has never been to Tibet like me, The Handsome Monk and Other Stories by TSERING DÖNDRUP is a satisfactory read. Thanks to Christopher Peacock’s translation, it becomes a reality for us non-Tibetan speakers to have a taste of genuine Tibetan culture. This perfect translation does not deprive the Tibetan essence from TSERING DÖNDRUP’s writings. By contrast, it justifies how witty the author is in mastering humour in his writing.

Many hold the imagination that Tibet, the sky is often high clear blue and the grass refreshingly green. This may also be true. But the Tibet of TSERING DÖNDRUP is more than just a bland description of natural environment. He writes about the themes which respond to a modernised society including corruption, religion, injustices, and social ills and so on. What interests me is the frequent appearance of the Lord of Death. Although China claims to be an atheist country, the Lord of Death is no stranger. TSERING DÖNDRUP’s creative power manifests through putting a traditional spiritual god in a modern context. He works in a Western-style office, uses a calculator and computers. I am brought closer to him by these items which I also encounter on a daily basis. The worlds TSERING DÖNDRUP offers, be it Hell or Tsezhung County, reflect the transformation of a Tibetan mind after the ‘liberation’ by the People’s Republic.

What I have paid attention to the most is also the humanitarian note woven into the stories. For example in One Mani, the two sworn brothers, Gendün Dargyé and Tsering Samdrup, one is willing to sacrifice while the other is willing to accept. Their encounter with the Lord of Death reminds me of the human relations in this contemporary world. I am also invited to reflect on the material world which gives nothing more valuable than one mani. Again I am moved by the faith of the Tibetan people. This is also the evidence that they are not the same as my people, the Chinese. Surely they are adopting a modernised lifestyle and will continue to have the identity crisis of being a Tibetan or a Chinese or a Tibetan Chinese, their genuine faith in what they believe is able to help them clarify.

TSERING DÖNDRUP, however, handles the interactions between the Tibetans and the central government in a comparatively subtle way. This is in fact a wise move. The less direct the touch on intense political and ethnic conflicts, the more possible it is to create the room for the readers to put things into perspective. For English-speaking readers it is more possible to put more focus on how the Tibetans tackle with political suppression on the education of Tibetan language, and how they may resist the propaganda. For me as a Chinese from the Mainland, however, I understand that people are making different attempts to voice themselves even under strict control. The humour threaded through TSERING DÖNDRUP’s writing may do the trick. So does the Lord of Death.

Reviewed by Bing Wang

Reviewed by Ruth Matanda, 22/7/19

The Handsome Monk is a collection of short stories which bring to light some of the problems which those living in China as an ethnic minority face. The book, written by Tsering Döndrup, a Tibetan-Chinese author explores the different ways in which these minority communities are often affected by issues such as internal community violence, religion and even addiction.

The Handsome Monk is a collection of short stories which bring to light some of the problems which those living in China as an ethnic minority face. The book, written by Tsering Döndrup, a Tibetan-Chinese author explores the different ways in which these minority communities are often affected by issues such as internal community violence, religion and even addiction.

I loved the Tibet which Tsering Döndrup portrayed in the book mainly because it was a Tibet which I personally had never imagined existed. Like many people living in the Western world I had always had a superficial image of Tibet influenced by Western media and films and so in a way I saw The Handsome Monk as being a book where Döndrup subverts the foreign gaze. He challenges the image which many people in the West have of Tibet, an idyllic land filled with remnants of the ancient world full of old traditions and peaceful communities due to its historical ties with Buddhism. This critic of Western bias is presented in the story of "Ralo" where the foreign gaze is explored through the use of the two European tourists whose perception of the place and their interactions with the locals are based on their own preconceived stereotypes, the violent and volatile situation which the characters in the story face are juxtaposed against the idyllic image the tourists have of the community.

The Tibet which the author showcases in each of the stories is one where the majority of people are seen as being morally corrupt and easily susceptible to indulging in negative behaviour, whether it is engaging in lustful actions in stories in The Handsome Monk which revolve around the struggles the holy individual has with abandoning the pleasures of the world to greed in "A Story to Delight the Masses" or in wrath such as that found in tales such as "Revenge" and "Brothers".

One thing which particularly stood out to me is the way in which each of these behaviours were presented as being cyclical, learnt behaviours and tendencies passed down from one generation to another making them difficult to resolve. Stories such as "Revenge" take a closer look at how these communities perpetuate and maintain violence because of traditional customs and beliefs while "Mahjong" is an analysis of how crippling addiction can be to a community.

The book also looks at how external factors affect these communities with the biggest factor being the Chinese government. "The Story of the Moon", for example, was an interesting take on the topic of climate change which is partly driven by the desire of modernisation from the Chinese government, and the author does a great job of highlighting the ways in which the destruction of a land impacts a community. For me I thought that it perfectly encapsulated the core messages of each of the stories, self destruction of communities, of cultures and of the self due to greed and government turning a blind eye to important issues and instead looking at profit, one bad situation becomes replaced by another.

This idea is reinforced in "Black Fox Valley" where we see the result of the greed and corruption; the exploitation of ethnic minorities and forced migration, allowing the government to have control over their land and resources.

I highly enjoyed reading this book and thought each story was one that needed to be told. In the West we often have discourses regarding the changing face of China and the impact its socio-economic development is having on Chinese culture, however very few of us consider how China’s development is also affecting and influencing the development of its ethnic minority communities.

The Handsome Monk portrays a Tibet under development and looks at some of the negative ways this development is changing the culture of the region. The stories themselves can be interpreted as being a microcosm of Tibet, each story is able to stand alone on its own and also be viewed as being connected to the others due to the coherency and the similarities of the themes explored, forming a complete narrative. Tsering Döndrup does a fantastic job with this book, upon completing it, I found myself becoming interested in learning more about the social and political realities of modern day Tibet of the role in which religion plays and how China’s influence in the region is reshaping Tibet’s culture.

Reviewed by Ruth Matanda

Reviewed by Tamara McCombe, 3/4/19

The Handsome Monk is a collection of cautionary tales about the Tibetan minority written by ethnically Mongolian Tsering Döndrup. This was my first reading of a Tibetan author. Although the collection touched on novel themes such as nomadic life and the central importance of Tibetan Buddhism over politics there were certainly common traits to contemporaneous Chinese authors such as the corruption of morality in today’s society. This is perhaps because all aspects of Tibetan society are closely observed and steered by the Chinese government, especially since the 2008 unrest in Tibet. Each story stands alone but there are common characters and themes which reoccur. Two strong themes are the decline in morals maintained, especially by monks, and the destruction by external forces of the environment so intrinsic to traditional Tibetan nomadic life.

The Handsome Monk is a collection of cautionary tales about the Tibetan minority written by ethnically Mongolian Tsering Döndrup. This was my first reading of a Tibetan author. Although the collection touched on novel themes such as nomadic life and the central importance of Tibetan Buddhism over politics there were certainly common traits to contemporaneous Chinese authors such as the corruption of morality in today’s society. This is perhaps because all aspects of Tibetan society are closely observed and steered by the Chinese government, especially since the 2008 unrest in Tibet. Each story stands alone but there are common characters and themes which reoccur. Two strong themes are the decline in morals maintained, especially by monks, and the destruction by external forces of the environment so intrinsic to traditional Tibetan nomadic life.

Regarding the first of these themes, the collection is bitingly critical of the way Tibetan society is evolving under Chinese political influence. Extortionist Buddhist monks collect dry the money off nomads on the auspice of helping the temple whilst they enjoy the ills of alcohol and women, young nomads quickly forget the need to work once their stomachs are full and young officials pander to higher ranking officials for personal gain and protection. However, these actions do not go unpunished. The young official trying to impress his professional superiors by employing sex workers contracts AIDS after an ill-fated night, the nomad who neglects his land and wife loses both and neither of the brothers feuding over family land get what they want. Unfortunately Döndrup’s criticisms are not unfounded. On my own trip to the sacred Potala Palace in Tibet I witnessed monks trading drugs on the monastery’s rooftop and withdrawing cash from ATMs – ‘open deeds’ indeed!

The second of these themes is particularly laid bare in episodes ‘The Story of the Moon’ and ‘Black Fox Valley’. The former sees a grandpa describing the appearance of the now destroyed moon to a disbelieving group of children. The latter recounts a family being relocated by the Chinese government. At first they are delighted with the benevolence they receive but slowly realise they are living in a community built on collapsing buildings and diluted milk. Here, the author makes undeniable reference to the tainted baby milk formula scandals and collapsed schools amid earthquakes, events which both took place in 2008. When the family try to cut their losses and return to their home pasture they discover the Chinese government has caused irreparable change. The disdain of Chinese officialdom and the way that it ignores the individuality of ethnic groups is profoundly displayed by the fact the author does not give any of Chinese official characters names.

Döndrup’s writing appealed to me. The single third person narrator is reminiscent of childhood tales, a welcome revisited style after so much stream of consciousness and first person narratives we see in contemporary literature across the globe. Although some of the writing lacked finesse, the tales were short and sharply made their point. This abruptness only adds layers of farce to the characters and their stories. Döndrup is a refreshing change from the many self-indulgent authors coming out of China. If one is to take him as an ambassador for Tibetan literature, I hope international publishers will support the proliferation of other Tibetan authors. There may well be other rough diamonds waiting for polishing.

Reviewed by Tamara McCombe

Reviewed by Paul Woods, 25/3/19

This is the first book by a Tibetan author that I have had the pleasure to read. It is always rather difficult to review a collection of short stories.

This is the first book by a Tibetan author that I have had the pleasure to read. It is always rather difficult to review a collection of short stories.

The first half of the book is dominated by the rather long ‘Ralo’, a fairly simple narrative concerning the unhappy life of the central character. By contrast, some of the other stories, particularly the shorter ones, have the feel of folk stories or fables. There is often a moral lesson or the reader is left with something to think about. That is not to say that the stories are moralistic or heavy-handed in any kind of didactic sense but the reader does come away pondering about the morality, motivations, and fate of the characters. There are even a couple of stories in which characters interact with the supernatural realm and the forces of karmic Buddhism. Some of these verge on speculative fiction, especially the story in which the Lord of Death sits behind a desk and uses modern technology in his work. In another tale, groups of what can only be described as Buddhist civil servants calculate the merit and decide the fate of the recently deceased. This bringing together of modern technology, efficient management structures, and Buddhist theology made for very interesting and readable stories. See for example, 'A Show to Delight the Masses' and 'One Mani'. In 'The Story of the Moon' we find a Tibetan critique of reckless modernisation located on what seems to be a post-apocalyptic earth.

However, although these stories are quite different from each other, they do have certain elements in common. If there is a dominant motif in this collection, then I think it has to be Tibetan Buddhism. The author does not appear to critique Buddhism itself, but rather hypocritical attitudes among adherents of varying degrees of piety. Indeed, the introduction to the book draws attention to ‘corrupt lamas’. Döndrup is also critical of Chinese communism, although again he is careful to draw attention to failures of practice rather than the ideology itself. This is not a political book.

His representation of his compatriots is interesting. In many of the stories Tibetan people come across as rather down on their luck and to some extent even as victims. 'Black Fox Valley' is the deeply moving story of the naiveté of simple, honest people who agreed to move to a new village in line with state policy and the promise of a better life. It ends in tragedy as they become disillusioned with their ‘ecological village’ and when they try to return to their valley it has become the site of a huge coalmine. The book does not portray Han Chinese negatively but where they do appear they seem to be more urbane and better able to cope with life in this complex and difficult region of China. At the same time, quite a few of the Tibetan characters are rascals and there are several slippery characters, people who always find a way to get what they want. Döndrup does not hold back from commenting on social problems such as gambling, prostitution, excessive drinking, clan warfare, and AIDS. Those who may wish to romanticise Tibet or perhaps see it as the last stronghold of something other worldly and holy might be a little disappointed.

There are quite a few Tibetan words and phrases in the book and it might have been useful to have some of these explained. Non-Chinese speakers may also have appreciated the same for Chinese words. I found the English translation smooth and very easy to read. I also like the fact that certain Tibetan misunderstandings of Chinese were rendered into amusing and awkward English. This is quite an achievement and I commend the translator for it.

All in all, the collection was surprisingly eclectic, not only in terms of the subject material but also the kinds of stories. I have to confess that this first collection of Tibetan short stories displayed more variety and social comment that I anticipated when I first saw the cover. That was a very pleasant surprise and experience.

At the end of the book, although there are many funny and ironic episodes and stories with the pithy flavour of Aesop’s Fables, I came away feeling a little wistful. Tibetan people seem to be struggling and many from traditional, nomadic backgrounds are faced with the gradual erosion or destruction of a way of life they have known for centuries. Urbanisation, modernisation, technology, and yes, the influx of Han Chinese, are bringing many challenges for these people. All cultures are changing and there is no reason why we should expect Tibet’s to be frozen and totally insulated from outside influences. But at the same time this collection of short stories suggests that Tibetans are far from masters of their own fate. Is Döndrup hinting at something about karma here?

Reviewed by Paul Woods

Reviewed by Cat Hanson, 24/3/19

Tibet is often a place represented in mainstream media as fixed in time. An orientalist lens pans over temples nestled in snow-capped peaks. The sound of monks chanting competes with the howling mountain winds buffeting wooden doors against their hinges. This is a place where we see flawed and gritty Hollywood characters come to their senses and see the light. A pocket of the world shielded from the trivial pursuits of the modern age.

Tibet is often a place represented in mainstream media as fixed in time. An orientalist lens pans over temples nestled in snow-capped peaks. The sound of monks chanting competes with the howling mountain winds buffeting wooden doors against their hinges. This is a place where we see flawed and gritty Hollywood characters come to their senses and see the light. A pocket of the world shielded from the trivial pursuits of the modern age.

Really, it’s us – the audience – who need to come to our senses. Tsering Döndrup’s short stories send the orientalist lens clattering to the ground, in what is a valuable opportunity to read stories based on Tibetan identity, relationships, and culture.

Tsering Döndrup depicts a Tibet of tradition and religion existing in the space of the ‘New China’ – bringing with it courthouses and bureaus and officials. This reoccurring bureaucratic presence in the short stories seemed to serve as a reminder of how modern Tibetan literature must now often exist with online spaces regulated by the CCP, alongside the author’s creative choices to name religious figure as Alak Drong (yak) so as to avoid accusations of referring to real figures or places (Introduction, pg 8). The influence on modern Tibetan literature is therefore twofold in historical background and limitations of expression.

The interaction between our Tibetan characters and the new systems emerging around them is introduced piece by piece. Throughout each story, a presence grows stronger, intertwining with characters’ experiences in varying ways. Formerly nomadic families move into newly built housing. Even the moon is a ‘curved sickle.’ (Ralo, 38)

Furthermore, while we read through characters’ experiences existing in ‘New China’, we are often reminded of ethnic identity of ‘Tibetan’ and ‘Chinese’ characters, a commentary on Tibetans’ classification as one of the 56 ethnic minorities in the People’s Republic of China. For example, ‘Students from nomad areas had a bad habit of not coming back on time for the start of the term.’ (Ralo, 30) says one line. The newly-enforced status quo singles out nomad students for non-conformance – the addition of ‘bad’ as a descriptor stuck out for me as this perhaps being an assumption of nomad students’ reputation from observers – who says it’s bad? Why? A distance is not only felt on one side: ‘Chinese rely on writing, Tibetans rely on their word,’as they say.” (Ralo, 45) says our main character as he explains his sudden shock at being told that only a written marriage certificate can prove his union. As noted in the Introduction, ‘virtually no one remains unscathed’ by the author’s satirical takes on cultural practises, materialism, and stereotypes.

My favorite story had to be ‘A Show to Delight the Masses’, translated by Lauran Hartley. The characterization of the Lord of Death as corporate CEO with PSB-like guards fetching newly deceased beings, as well as court proceedings with your personal lha and personal dü (92) acting as your defense and prosecution, really brought forth the setting of the ‘New China.’ We picture spiritual practices and prayers as insurance and savings accounts in One Mani: ‘What’ll we do if the Lord of Death says your mani can’t be transferred to my account? (111) As if prayers are simply another form of currency to barter and trade and deposit. What effect is this new economic era of Reform and Opening Up having

on Tibet? we wonder.

Translator Christopher Peacock leaves in just enough of the original language and dialogue so that we are always reminded of our setting. The translation maintains the pacing and humour of the characters’ interactions and nothing seems clumsily explained. As the reader, you feel confident to picture the settings and characters yourself. It’s a wonderful experience for anyone hoping to expand their concept of modern Tibet.

As mentioned by Christopher Peacock, Tsering Döndrup also doesn’t shy away from showing you the problems of modern Tibet. Characters have their own vices, make mistakes, and monks are hardly devout. However, it is the raw account that makes us sit up and pay attention. This isn’t just more stories of a Tibet existing in a snapshot from time – this is a living, breathing place with amazing and flawed stories.

Reviewed by Cat Hanson

Reviewed by Kevin McGeary, 5/3/19

In China, authors from minority ethnic groups are often forced to write in Chinese to get noticed. That means using a second language, in some cases one from a different family of languages, to tell the story of their own people.

In China, authors from minority ethnic groups are often forced to write in Chinese to get noticed. That means using a second language, in some cases one from a different family of languages, to tell the story of their own people.

In the introduction to The Handsome Monk, a short story collection by Tsering Döndrup, translator Christopher Peacock points out: “Tibetan authors publish through journals and publishers organized under Chinese state practices, and likewise, online literature is largely circulated on websites and platforms hosted in China.” This puts Tibetans in danger of having a shortage of authentic literary voices.

Fortunately, Döndrup, who is originally Mongolian but widely recognised as one of the most important writers in Tibetan of recent decades, has provided a vital and entertaining collection, mostly set in the fictional county of Tsezhung, a rural nomad locale along the real-life Tsechu River in his home region of Malho, Qinghai. Translated brilliantly from the Tibetan by Peacock, the stories humanize the nomadic Tibetan people while satirizing their society as one plagued by gambling, prostitution and religious hypocrisy.

The author is something of a specialist in conjuring up vivid scenes using bodily fluids. “Piss and Pride” is a rather suspenseful story, centring on a retiree who must test his bladder control to the maximum to uphold the dignity of his people. In “Notes of a Volunteer AIDS Worker”, the narrator graphically details how he contracted the disease and what it is doing to his body.

In “Ralo”, the titular character is known for the prodigious amount of snot that he produces. Initially published in the early nineties, this story was later extended to novella length. It is not one of the tighter pieces but contains some very astute satire about how Western tourists see Tibet as “the last unspoilt holy land on Earth”.

The collection is at its strongest when characters are grappling with the moral implications of their own behaviour. Many of these involve the Tibetan people being dominated by the Han and succumbing to the kind of anguished compromises required to survive.

One of the most extraordinary of the stories is “A Show to Delight the Masses”, which carries on the Tibetan tradition of mixing prose and poetry in summing up the life of corrupt official Lozang Gyatso. Much of the narrative unfolds in a sort of celestial rap battle to decide whether the main character is a good person. Since his sins have included urinating in a monk’s mouth, the answer is somewhat self-evident, but the story is no less gripping for it.

Standout lines include: “If you send this man to hell, you’ll have to send the rest/ The eighteen realms will overflow, and that will be a mess”. Unfortunately, Robert Frost’s quote that “poetry is what gets lost in translation” applies, and rhyme and meter often have to be sacrificed for accuracy. It is nonetheless a radical and interesting idea, brilliantly carried through.

In the title story, the eponymous handsome monk Gendün Gyatso encounters Llatso. He gradually goes from seeing indulging the pleasures of the flesh as unthinkable, to acceptable, to an addiction.

Of the shorter pieces, highlights include “Revenge”, which hints at the intractability of the society’s problems. “A Story of the Moon” is an other-worldly fable that expresses Döndrup’s scepticism of technological progress.

The penultimate piece “Black Fox Valley” also satirizes the idea of social progress with the very real issue of Han encroachment on Tibetan culture. A family of nomads are relocated from the idyllic valley to the ominously named Happy Ecological Resettlement Village.

The nomads observe what a hypocritical invention the modern toilet is, and that dung is becoming rarer and being replaced by a much deadlier fuel, coal. After experiencing a family tragedy that echoes something from China’s recent past, the nomads attempt to return to the valley, but may be in for another shock.

Since the unrest of 2008 and the periodic self-immolations of the following years, Tibet has been the subject of a crackdown. Döndrup, with the help of translator Peacock (and Lauran Hartley for the story “A Show to Delight the Masses”) brings a massively readable collection with a real and respectful portrayal of this fascinating land.

Reviewed by Kevin McGeary