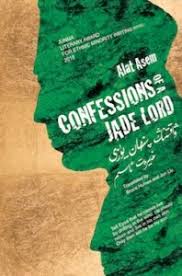

Confessions of a Jade Lord, by Alat Asem

translated by Bruce Humes and Jun Liu

Aurora Publishing LLC, 2017

Publisher's blurb

Confessions of a Jade Lord immerses us in an underworld peopled by gangsters with their penchant for firewater-fueled storytelling and philosophical reverie,appetite for Uyghur delicacies such as lagman hand-pulled noodles and whole roasted  lamb,fierce loyalty to family and aghines, and a willingness to unsheathe their daggers when honour, brotherhood or jade require.

lamb,fierce loyalty to family and aghines, and a willingness to unsheathe their daggers when honour, brotherhood or jade require.

Alat Asem's fiction is a Uyghur universe where Han Chinese rarely figure. His hallmarks are serial womanizers -- real hanzi who piss standing, not squatting -- monikers that belittle, and a hybrid lingo with an odd but appealing Central Asian flavour.

Reading Chinese Network Reviews

Reviewed by Cuilin Sang, 22/12/18

Confessions of a Jade Lord is a story about time. In fact, it is obsessed with time. Its original Chinese title, if literally translated, would be something like "The Secret Face of Time" (时间悄悄的嘴脸). Or, if even more literally, it would be "The Secret Mouth-Face of Time", which probably wouldn’t make much sense in English. “Mouth-face” (嘴脸), a term carrying negative connotations on most occasions, refers to a person’s appearance and behavior especially after he/she has done something despicable. But in this book, “mouth-face” has neutral connotations and is applied to time. The author, Alat Asem, a Uyghur born in Xinjiang, China, who writes in both Chinese and Uyghur, chose to write the story in Chinese and by doing so has enriched the language with “exotic” metaphors, fresh juxtapositions of phrases, and extended connotations for words. Speaking through his protagonist, Eysa, or Eysa ASAP with his moniker, the author dwells on the subject of time extensively. Time is treated as a trickster-like personality, a concrete being, instead of something inconceivable or intangible. The beautifully translated last section, titled “Time’s Eternal Chant”, may offer a glimpse of the author’s impassioned musing on time:

Confessions of a Jade Lord is a story about time. In fact, it is obsessed with time. Its original Chinese title, if literally translated, would be something like "The Secret Face of Time" (时间悄悄的嘴脸). Or, if even more literally, it would be "The Secret Mouth-Face of Time", which probably wouldn’t make much sense in English. “Mouth-face” (嘴脸), a term carrying negative connotations on most occasions, refers to a person’s appearance and behavior especially after he/she has done something despicable. But in this book, “mouth-face” has neutral connotations and is applied to time. The author, Alat Asem, a Uyghur born in Xinjiang, China, who writes in both Chinese and Uyghur, chose to write the story in Chinese and by doing so has enriched the language with “exotic” metaphors, fresh juxtapositions of phrases, and extended connotations for words. Speaking through his protagonist, Eysa, or Eysa ASAP with his moniker, the author dwells on the subject of time extensively. Time is treated as a trickster-like personality, a concrete being, instead of something inconceivable or intangible. The beautifully translated last section, titled “Time’s Eternal Chant”, may offer a glimpse of the author’s impassioned musing on time:

"Myriad are the facets of Time, like a sea of glorious fluttering banderoles. Some triumphant after battle; some true as blood is red; some debauched; some shamelessly wretched, and some silent but expectant. Yet ancient legends have chronicled al things worthy of record."… (p. 281)

Blending aphorism, Uyghur idioms, verbalized adjectives and so many other ingredients, Alat Asem tells a contemporary story in an ancient and timeless voice. The co-translators, Bruce Humes and Jun Liu, have done an amazing job rendering this work written in a Chinese commingling the north-western dialect, the mainstream literary mandarin, and the Uyghur mentality into flawlessly enjoyable English. It’s refreshing and invigorating to see that Chinese language, and, for that matter, English language, have the capacity to collaborate with a literary expression that bears such remarkable and distinctive marks of Uyghur culture. The current English title of the book brings into relief its predominant feature: it is a folkloric, spiritual adventure, a bildungsroman of a middle-aged, religious man in the business of jade trade.

Despite its convoluted storylines, Alat Asem writes emphatically on two psychological and emotional experiences of the protagonist: one is his mother’s death, the other is the tour of his homeland he gives to his friends from Shanghai. The perspective shifts occasionally from the protagonist to other characters who are involved in these experiences, but there is no denying that Eysa is the one most impacted by them. If the three-day fast and soul-searching after his mother’s death make him realize the blessedness of a simple, honest life, then revisiting the breathtaking beauty of nature in his homeland with his friends from Shanghai reawakes his passion for earth and for the harmony between human and nature.

Confessions is fundamentally a story about empathy and forgiveness, perhaps more so about the latter than the former. What differentiates it most from other Chinese-language literary works is perhaps the fact that it deals with these subjects from a religious perspective. It brings hope and certainty to the uncertainties brought by desire in a money-seeking culture. It takes revenge out of human’s hands (literally), and encourages receiving suffering, loss and unfairness with a mind heedful of the presence of Allah.

Regarding the secular social values, Confessions doesn’t provide an easy answer. More than once describing the “real man” (zhenhanzi) as the man “who piss[es] standing, not squatting”, Confessions lauds women’s loyalty to men and men’s true valor as the generosity of the heart. There is an episode about Eysa’s mother Minewer getting confused about the reason why people should vehemently criticize Confucius during the Cultural Revolution, whose ideas about women serving men, after being explained to her, seem only fit and truly understanding of women. As the real pillar of the family, Minewer is depicted as the model of the true women: generous, hard-working, forgiving, accepting, and most importantly, with a mind that knows how to tend their men and livestock.

Another example of values would be the care for non-human life. There are abundant descriptions of food, especially of lamb. The moral predicament of loving animals (his beloved black-headed white lamb, for example) and eating them, the guilt from strangling a sparrow in his childhood, the frequent reflections on life, seem to have reached no obvious reconciliation.

There are, occasionally, discrepancies between the Chinese version from People’s Literary Press (2013) of the book and its English version. In the chapter titled “The Good Doc Travels to Xinjiang”, Eysa’s view on the hierarchical order of the city is omitted in the English version. He insists on bringing his friends from Shanghai to the poor people’s market, for his idea of a real city is one which consists of philosophers, the mayor, businessmen, lackeys, doctors, beggars, police, poor people, thieves, pimps, the rich, the class of leisure, snitchers, and lobbyists. Another example would be the chapter entitled “Hometown, the Heart’s Resting Place”, in the beginning of which Eysa and his “after-hours’ girlfriend” Xeyrigul’s dialogue is shortened, with Eysa’s few lines on men and women missing.

Reviewed by Cuilin Sang

Reviewed by Paul Woods, 20/11/18

This 300-page volume is a full-length novel set in Xinjiang and most of its protagonists are Uyghurs. It is the first piece of fiction written by a Uyghur author that I have read.

This 300-page volume is a full-length novel set in Xinjiang and most of its protagonists are Uyghurs. It is the first piece of fiction written by a Uyghur author that I have read.

The use of ‘lord’ in the title brings obvious parallels with the idea of ‘drug lord’ and it is clear from the outset that while the jade trade is nowhere near as destructive and socially undesirable as that in drugs, it does have a darker side. Many of those involved in it employ dubious methods and consciously site themselves at the edge of criminality. There is an ‘ask no questions’ atmosphere in which jade changes hands and often ends up on China’s rich eastern seaboard.

The story is of Eysa, a Uyghur man who has become rich by dealing in jade and selling it to Uyghur and Han customers in Xinjiang and the rest of China. Eysa has to flee Xinjiang after seriously injuring a competitor in the jade business and decides to ask a Han customer in Shanghai to help him with plastic surgery. The details of the surgery are not clear, but the results are described as a ‘mask’ which means that even close relatives and friends cannot identify Eysa on his return to Xinjiang. I have to say that I did not find the ‘mask’ convincing. It seems not to have been the result of face-altering plastic surgery, yet Eysa was not recognisable to people who had known him since he was a child. For me this was a weak element in the story.

Eysa spends some time there cultivating friends and gathering intelligence on the situation on the ground and in the jade business by pretending to be Mijit, a previously unknown ‘kidney-brother’ of the missing Eysa. After many adventures Eysa decides to have the ‘mask’ removed and asks his doctor friend in Shanghai to do this. Without ever revealing that he and Mijit were one and the same, Eysa works to put right many of his previous misdeeds and make amends for hurt he has caused, including the attack on Xali, his erstwhile competitor in the business.

Eysa’s change of heart is partly caused by his mother’s wisdom and love for him, as well as the realisation that having lots of money but few real friends amounts to a second-class existence. At the end of the story, after much drama, Eysa is reconciled to Xali and even his violent and evil son.

The story is interesting as a first look into the lives and customs of Uyghur people, whom I have only ever come across in China selling lamb kebabs and working in restaurants. While the tale is one of redemption and a man returning to the ways of goodness and righteousness, giving and receiving forgiveness, it also reinforces traditional values and practices.

The characters in the story are strongly gendered. Apart from Eysa’s mother, most of the other female characters take supporting roles; they appear providing food, in the service sector, and in the roles of wives and mistresses. The male characters are primarily rogues, lovable and detestable, enjoying large amounts of strong drink, big chunks of meat, and the company of women, as they jockey for position in the masculine world of the jade trade.

There is a clear distinction between the wisdom of the old and the foolishness of the young. Eysa’s wayward younger brother dies of a drug overdose and Xali’s son wishes to murder Eysa. It is when Eysa looks back over his life and temporary exile in Shanghai and then behind the ‘mask’ that he becomes open to the wisdom of his mother.

There is also an emphasis on harmony. Uyghur characters occasionally quote from Chinese sayings, Eysa’s plastic surgeon friend is Han, and relations between Uyghur and Han are portrayed as pleasant. Between the Uyghurs, the themes of harmony and friendship are evident, and Eysa realises that good interpersonal relationships are better than any amount of money. In addition, mention is made of face, honour, and respect. The author interacts with the secular-religious divide in Xinjiang and pious Muslims are described in positive and moderate terms. It is hard to know how much Alat Asem is describing contemporary Uyghur society and its values and how much he is prescribing and aspiring. The novel won a prize in China and it is thus unlikely that the author would delve into the murky area of Uyghur-Han tensions.

Having only seen pictures of Xinjiang and heard from friends and relatives who have been there, the novel increased my desire to visit the area and learn more about the Uyghur people. The author certainly portrays his people as different from the Han.

The English translation reads well, but while the spelling is American the idiom seems to flip-flop between British and American. The pronunciation guide at the beginning is useful and I enjoyed the sprinkling of Uyghur words throughout the story.

I would recommend the story as a first experience of Uyghur literature and the world from which it springs, but I would hope to see greater depth, complexity, and intrigue in future fictional trips to Xinjiang.

Reviewed by Paul Woods