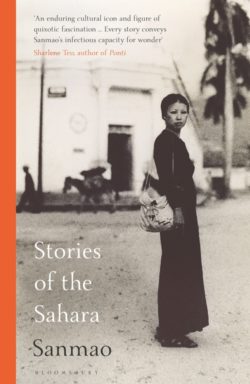

Stories of the Sahara, by Sanmao

translated by Mike Fu

Bloomsbury, 2020

Publisher's Blurb

The book that has captivated millions of Chinese readers, translated into English for the very first time.

Sanmao: author, adventurer, pioneer. Born in China in 1943, she moved from Chongqing to Taiwan, Spain to Germany, the Canary Islands to Central America, and, for several years in the 1970s, to the Sahara.

Stories of the Sahara invites us into Sanmao's extraordinary life in the desert: her experiences of love and loss, freedom and peril, all told with a voice as spirited as it is timeless.

At a period when China was beginning to look beyond its borders, Sanmao fired the imagination of millions and inspired a new generation. With an introduction by Sharlene Teo, author of Ponti, this is an essential collection from one of the twentieth century's most iconic figures.

'Hypnotic . . . A record of one person's fierce refusal to follow a path laid down for her by the rest of the world' Tash Aw, Paris Review Books of the Year

Reading Chinese Network Reviews

Reviewed by Simona Siegel, 25/3/22

Stories of the Sahara is an extraordinary biography written by Taiwanese author and adventurer Sanmao. Before reading the book, the only thing I knew was that it was an autobiographical novel about her years spent in the Sahara. After reading, I feel connected with her on more levels than I could have ever imagined. It is a very intimate story about a remarkable woman and an important period of the history of one interesting part of the world.

Stories of the Sahara is an extraordinary biography written by Taiwanese author and adventurer Sanmao. Before reading the book, the only thing I knew was that it was an autobiographical novel about her years spent in the Sahara. After reading, I feel connected with her on more levels than I could have ever imagined. It is a very intimate story about a remarkable woman and an important period of the history of one interesting part of the world.

The desert is a world in itself. There are two types of people in the world, either they don't care about it at all, or they hear a strange calling compelling them to go and see it. With Sanmao, it was the second. She let her then-partner know that she was about to move to the Sahara for God-knows how long. And he followed her. It was the beginning of the love story, not only between the two of them, but with the Sahara as well.

The book is divided into two parts. The first one is more optimistic, about moving to the Sahara, furnishing the house, the way Sanmao was helping the local people, and her wedding. The second was more raw, with the historical events, fighting, and the hardship of living away from family and friends, among strangers with different habits and mentality. I admired Sanmao on every page, how she endured the hard life, heatwaves, neighbors, and even her new life with her husband. José cannot be forgotten either, it would have been interesting to read his version of the story.

Furthermore, the author, maybe unintentionally, created a very interesting cultural “guidebook” to the Chinese, Taiwanese and Spanish cultures, and the comparison among them. Both main protagonists, Sanmao and José, not only have to face the new Sahrawi culture, but the differences among their own cultures and try to find a compromise. It was very evident around the time of their marriage. A day before, Sanmao just sent a brief telegram to her parents, as she knew they would be finally at peace knowing that she settled down and was being taken care of. After the wedding, she regularly sent letters even to her parents-in-law about their life in the Sahara, even though José didn't mind doing it himself. This could be the impact of the feeling of filial piety, which is so strong in Chinese culture. Or one can argue she was doing it out of boredom. But after reading this book, I think there was never a dull day for them in that wilderness, so that could hardly have been the reason for her to write letters regularly to her in-laws.

One of my favorite chapters was the one about traveling to Spain to spend Christmas with José's family. The way Sanmao was freaking out before going and during the whole stay, I found it rather too much. She saw her mother-in-law as an enemy and herself as the one who had to fight for her husband with his own mother. From a cultural point of view, in many countries a son is the “chosen” one and his wife is “an enemy” in the eyes of a mother-in-law. In traditional Chinese culture, the daughter-in-law was more like a servant, that had to endure the pressure the mother-in-law was putting on her shoulder, and if she wanted to oppose, there was no one she could turn to. So Sanmao saw her trip to Spain in the same way, and this only intensified when she was asked to cook Christmas dinner for the whole family without help from anybody. The author was scared, ready to fight, disappointed with the behavior of her husband, but mostly shocked when her mother-in-law hugged her at the end of the trip, and started to consider her as own daughter. With the words she used, I had the feeling that probably Sanmao wasn't exaggerating when she said she had mixed feelings about her mother-in-law at first.

Last but not least is the topic of food. Without knowing much about the desert, the difficulties of securing water and food in general are obvious. However, for Sanmao it was important to cook for her husband everyday and to serve him nutritional food. So she went to the shop daily (not an easy task), she even made friends with soldiers and started to go to their shop where she could buy cheaper ingredients. She also made friends with a local guy, who was illiterate but trusted her when she was writing down all the things she bought and paid for when she reached the certain amount. And the moments when everyone from José's company got invited to their house and she cooked Chinese food for them - in the middle of the desert - a miracle, at least for me. Cooking, for her, even in such hostile conditions was a priority and way of keeping with her roots even being so far away from family and friends. She learnt how to treat illnesses with wit and the help of Chinese herbs, which was extremely helpful for local people, as well as it helped her to get closer to the Sahrawi culture.

“What attracts me to this place? The wide openness of the earth and sky, the hot sun, the windstorms. There's joy in such a lonely life, there's sorrow. I even love and hate these ignorant people. It's so confusing! I can't quite make sense of it myself (p.319).” I have a similar feeling about one particular country as well. But like Sanmao, and many other people with similar feelings, we will hardly ever become a part of the new country and culture. We can learn the language, we can experience key historical events there in person, but there will always be something invisible that is separating “us” from “them”. Which eventually might be good, because that is how the new “mixture” and the new story are created. And this one about Sanmao and José in the Sahara is certainly amazing.

Reviewed by Simona Siegel

Reviewed by Stephanie Boote, 24/6/21

This collection of short stories in Tales From The Sahara creates a wonderful depiction of Sanmao’s time spent in the desert; I thoroughly enjoyed reading this book. Arriving with the grand expectation of becoming the first female explorer to cross the Sahara desert, she is unselfconscious in describing how this plan failed and the life she made for herself regardless. To me, it is that stubbornness that makes her so appealing as a protagonist. She is initially naïve it’s true -- her plan to cross the Sahara is made having only read one article in the National Geographic -- but you have to admire that she is nothing if not adventurous and confident. She forges connections with the Sahrawi community, builds a beautiful home in the graveyard district and pushes her way through some truly scary, impossible seeming situations (for example: "Night in the Wasteland"). Sanmao doesn’t embark on any daring exhibitions worthy of a review from the National Geographic, but the Sahara is uncomfortable and dangerous and beautiful, and she makes it her home. This is a really interesting read about travel and self-determination from a truly impressive woman.

This collection of short stories in Tales From The Sahara creates a wonderful depiction of Sanmao’s time spent in the desert; I thoroughly enjoyed reading this book. Arriving with the grand expectation of becoming the first female explorer to cross the Sahara desert, she is unselfconscious in describing how this plan failed and the life she made for herself regardless. To me, it is that stubbornness that makes her so appealing as a protagonist. She is initially naïve it’s true -- her plan to cross the Sahara is made having only read one article in the National Geographic -- but you have to admire that she is nothing if not adventurous and confident. She forges connections with the Sahrawi community, builds a beautiful home in the graveyard district and pushes her way through some truly scary, impossible seeming situations (for example: "Night in the Wasteland"). Sanmao doesn’t embark on any daring exhibitions worthy of a review from the National Geographic, but the Sahara is uncomfortable and dangerous and beautiful, and she makes it her home. This is a really interesting read about travel and self-determination from a truly impressive woman.

All at once Sanmao is a shamelessly voyeuristic outsider ("The Desert Bathing Spectacle") and a valued member of a squabbling community ("Nice Neighbours"). I did struggle to read some of her more patronising views on the Sahrawi, although I’m in agreement with her that accepting Child Marriage as a cultural difference is uncomfortable to say the least. Nevertheless, during her time in the desert she doesn’t hesitate to find connection with them and takes on the role of pharmacist and teacher among the women. I do disagree with Sharlene Theo’s statement in the preface that Sanmao has “No compunction” about acting as a local doctor with no medical training. In "Apothecary" she is clearly uncomfortable with her mounting responsibility. Although she does have the best intentions at heart, she is also very aware of her lack of training, mainly using her access to aspirin and multi vitamins as well as her own ingenuity to help them (Who knew nail polish could be so helpful?). The escalating expectations of her skills are stressful to read, they culminate in a dramatic scene where she’s begged to deliver a baby as the mother is unwilling to travel to see a male doctor. While she was willing to do it, it’s clear that this was not because she particularly wanted to, but because it seemed like the only option in a high-stress situation.

Subtly through the arrangement of the collection we see Sanmao’s narrow perspective of self-actualisation through travel expanded, and slowly we see that her developing understanding of the political context of the region will be devastating to her individual plans. I loved the way the stories gradually built a rounded picture of her time in the desert, getting just a bit darker and more widely significant as she adjusts to her surroundings. The first story "A Knife on a Desert Night" contrasts her initial goals with her (reasonable) ignorance, for example when she panics at her first sight of a mirage. Her expectations for her experience shift here and in a defining part of her story she chooses to follow the advice of a friend “There are weird things aplenty in the desert. Take your time discovering it!” From here the reader is taken with her as she explores her surroundings and becomes established there. These early stories are about her personal journey and say as much about who she is and her relationship with her husband Jose as they do about the desert itself.

However, once the earlier stories have shown her just living her life and acclimatising to the desert and Sahrawi culture, the last few grow darker and her reactions come with more understanding and context. This makes the politically and culturally charged events of the final stories, "Crying Camels" and "Lonesome Land", especially harrowing to read because Sanmao emotes a real sense of her familiarity there; the violence is happening to her friends and the politics will drive her away from what has finally become her home. The reader has spent the whole collection gaining such a sense of her becoming settled, but this in turn broadens her perspective, once she is comfortable and has built a network she can’t ignore the cultural shifts taking place. This inevitably leads to tragedy, as without her ignorance of the Sahara she has to acknowledge her fear and the reality that she isn’t safe. This provides us with the context of why she had to leave, despite the fact that she worked so hard to make it her home. Essentially, the initial stories are more about her own self-actualisation, but the last stories are about the events and contemporary culture of the Sahara itself. The organisation of these stories works really well to create this effect gradually.

Sanmao is a fascinating woman and I wish I’d known about her sooner, reading about her death in 1991 having just finished reading these stories was a shock and honestly it made me really sad. Mike Fu does a wonderful job of translating her voice into English and creating a collection which truly does her justice. I wholeheartedly recommend this book.

Reviewed by Stephanie Boote

Reviewed by Riya Shah, 23/6/21

"You do not travel if you are afraid of the unknown. You travel for the unknown, that reveals you within yourself." The words of Swiss adventurer Ella Maillart resonated in my ears incessantly as I read through Sanmao’s adventures in the unfathomable Sahara. The book is a collection of vignettes about her expeditions with the Sahrawis, the indigenous tribe who lived in the deserts for generations and her day-to-day encounters with the Spanish people as she navigates through life with her Spanish husband José María Quero.

"You do not travel if you are afraid of the unknown. You travel for the unknown, that reveals you within yourself." The words of Swiss adventurer Ella Maillart resonated in my ears incessantly as I read through Sanmao’s adventures in the unfathomable Sahara. The book is a collection of vignettes about her expeditions with the Sahrawis, the indigenous tribe who lived in the deserts for generations and her day-to-day encounters with the Spanish people as she navigates through life with her Spanish husband José María Quero.

Sanmao (born Chen Mao Ping) who is often described as the folksy traveller, wandering writer, bohemian expatriate, Taiwanese wayfarer, was a literary cultural icon of the 1970s. Her free-spirited travel writing was like an elixir to the exoticism-starved Chinese-speaking audience, who had just been introduced to the outside world. Her authentic voice offered a fresh perspective of a place that was an exotic, unseen mysterious land. The end of White Terror in Taiwan and the stable times under Deng Xiaoping allowed Sanmao’s writings to be circulated freely and she became an inspiration for women who wished to abandon traditional pathways and live life on their own terms. As described by Sharlene Teo in the foreword of the book, “Sanmao’s free-spirited itinerancy enthralled readers and demonstrated an exciting model of Asian femininity that centred personal agency, resourcefulness and reinvention.”

“When I first arrived in the desert, I desperately wanted to be the first female explorer to cross the Sahara.” The book begins with Sanmao’s solemn wish to conquer the Sahara which sets a warm and spirited tone for the entire collection and takes us through this roller-coaster journey where the reader and Sanmao are trapped in her story and become companions as the lines between fiction and memoir start blurring. Her daily, mundane experiences are filled with numerous vibrant emotions and dramatics. From goats eating her plants, to experiencing married life, to teaching poor local girls, to befriending an African slave, her depictions often transition from the humorous and light-hearted to the serious and dark.

Sanmao’s indomitable spirit and tenacity is depicted time and again in various chapters. In “Night in the Wasteland”, she fights off attackers when Jose is stuck in some quicksand, and in the “Seed of Death”, she wards off a deadly desert spell, hinting at superstitions and indulging in a little folklore prose style. Sanmao doesn’t create a romantic imagery of the desert, and in the chapter entitled “Hearth and Home”, she doesn’t shy away from detailing the difficulties that she faced while trying to adjust in the new, unfamiliar land. She writes, “I found the desert to be truly charming, but the desert didn’t care a jot for me. Which is as it should be. “

Her descriptions of the local Sahrawis hygiene habits and customs are uncensored and portray her truthful reporting style. Though she tried to meddle in the local customs a few times, she soon realized that it was of no avail. Her accounts of the fate of the guerrilla fighters and the conflict between the Spanish government and Sahrawis is honest and straightforward. The theme of isolation or ‘world weariness’ is also perceptible in Sanmao’s writings. In “A Knife on a Desert Night” she writes, “Every day as the sun went down, I’d sit on the roof until the sky was totally dark and feel an immense loneliness, out of nowhere, deep in my heart.” During such rare vulnerable moments, she seamlessly drifts to a confessional tenor.

Sanmao’s prose is breezy and lucid, and much credit needs to be given to Mike Fu who has successfully managed to retain the narrative flow of such a chronologically non-linear and culturally layered book. Stories of the Sahara was an immensely engaging read and the lyrical agility of Sanmao's writing style speaks louder than any fancy prose could.

Reviewed by Riya Shah

Reviewed by Kevin McGeary, 29/5/21

In The Picture of Dorian Gray – one of the most quotable novels ever written – it is claimed that second-rate writers are much more interesting people than first-rate writers. First-rate ones write the poetry they dare not live. Second-rate ones live the poetry they’re not quite good enough to write.

In The Picture of Dorian Gray – one of the most quotable novels ever written – it is claimed that second-rate writers are much more interesting people than first-rate writers. First-rate ones write the poetry they dare not live. Second-rate ones live the poetry they’re not quite good enough to write.

San Mao, perhaps the most quoted Chinese figure of the past century behind Chairman Mao and Lu Xun, was living proof that there are exceptions, top writers could live fascinating lives. In a culture where ‘falling leaves’ are expected to return to their roots, a nomadic lifestyle is a distant dream for most Chinese people, shackled by traditions of filial piety.

Her memoir Stories of the Sahara, a vivid account of intercultural experiences and harsh living conditions in North Africa during the dying days of Spanish colonialism, proved a sensation with China’s exoticism-starved reading public after it was first published in Taiwan in 1976. San Mao’s appeal is described in the foreword by Sharlene Teo as ‘an exciting model of Asian femininity that centred personal agency, resourcefulness and reinvention’.

At one point in her musings, San Mao asks herself: ‘All those hands that I’ve shaken, all those brilliant smiles exchanged, all those boring conversations, how could I just let a wind blow through my skirt and scatter these people into nothingness and indifference?’ Fortunately, she did not let her amazing experiences be forgotten like (as she puts it) ‘pebbles mixed up in the sand’.

Her adventures range from the amusing, to the historical, to the horrifying, to the nail-bitingly suspenseful.

Whereas in the English-speaking world, a common comedic trope is that of men clashing with their mothers-in-law, Chinese literature is awash with women who have difficult relationships with the woman who gave birth to their eventual husband. In the chapter ‘My Great Mother-in-Law’, San Mao prepares to meet the family of her Spanish husband Jose and steels herself for the bottomlessly sophisticated unspoken duels that might ensue with the women in his family.

The book also serves as an important historical document. The action takes place in El Aaiún at a time when tensions between Spanish occupiers and Sahrawi natives were high. Spanish colonialism is particularly embodied by the tragic drunken figure of Sergeant Salva who lost his brother and many comrades to Sahrawi guerrilla fighters.

Much of what she witnessed is vile by the sensibilities of the twenty-first century West, or 1970s China, including the forced marriages of pubescent and pre-pubescent girls. In all this, she was not a participant, but more than just an observer. A chapter titled ‘The Child Bride’ contains the following paragraph:

Abeidy came out with a bloodstained piece of white cloth later. His friends started shouting with lewd excitement. From their perspective, the whole point of the first night of marriage was to openly use force and violence to take a little girl’s virginity. That the ceremony had to conclude in such a way was deplorable and ridiculous. I got up and strode out without saying goodbye to anyone.

The most unputdownable section is one in which Jose is drowning in a quarry and San Mao seeks help from three men who then attempt to rape her. This sadly and unwittingly foreshadows Jose’s eventual death in a diving accident in 1979.

San Mao often carried a camera. At one point she reminisces: ‘It was too bad that we didn’t get a shot of the flamingos. But the beauty of that moment remains in my heart, something I will never in my life forget.’ San Mao’s life ended in 1991 in an apparent suicide, but many of the moments she put in words continue to live in millions of hearts.

The translation by Hubei-born Mike Fu flows as unaffectedly as the Chinese it was originally written in. It could give San Mao a well-earned reputation for one of the most extraordinary literary lives of the twentieth century.

Reviewed by Kevin McGeary

Reviewed by Tamara McCombe, 15/5/21

I have been studying Mandarin for nearly twenty years and reading Chinese fiction (both in the original and English translation) for fifteen, yet have never read anything like Sanmao’s Stories of the Sahara. Many of the works picked by publishers for Occidental readers are hyper-dystopian, angry texts considering the societal overhauls China has experienced since Deng Xiaoping’s ‘Opening Up’ reform period in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Often, female characters are portrayed as weak, subjugated victims and moral decline seeps into every corner. However, this work is a candid reflection by a strong-willed author of her experience of living in the Sahara during the 1970s as the region moved to independence from Spanish colonialization.

I have been studying Mandarin for nearly twenty years and reading Chinese fiction (both in the original and English translation) for fifteen, yet have never read anything like Sanmao’s Stories of the Sahara. Many of the works picked by publishers for Occidental readers are hyper-dystopian, angry texts considering the societal overhauls China has experienced since Deng Xiaoping’s ‘Opening Up’ reform period in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Often, female characters are portrayed as weak, subjugated victims and moral decline seeps into every corner. However, this work is a candid reflection by a strong-willed author of her experience of living in the Sahara during the 1970s as the region moved to independence from Spanish colonialization.

What will immediately strike regular readers of Chinese literature in translation is how fluid Mike Fu’s English translation is; it reads as naturally as though the text was originally penned in English. Sometimes more literal translations from the Chinese original aid the reader to slide into oriental settings but Sanmao’s poetic descriptions are better shared with readers by a translator with a penchant for lyrics – being Chinese, brought up in the US, and an academic at the Parsons School of Design, Fu’s translation shows himself a master of both Chinese and English. His translation is sublime. Fu explains that the translation was a labour of love and homage to Chen Ping (Sanmao was her pen name), a result of meetings with her family and friends and international trips. This dedication to his heroine is a gift to the non-Chinese speaking world, introducing us to an infectiously life-loving soul. Although a well-known name within the Chinese diaspora, it is a shame she is only now more readily known to English audiences.

Stories was originally serialised for Taiwan’s United Daily News. This is quite evident in that each chapter covers disparate topics from how to get on with your in-laws and make a cosy home from few resources, to spontaneous desert shenanigans and portraits of individual characters who strike Sanmao’s intrigue. This could have leant the collected chapters an air of discontinuity; however, they reek more of an intimate epistolary account to a friend where she repeats introductions or descriptions in case the recipient has forgotten characters or setting from previous letters. Those familiar with Alistair Cooke’s reporting will appreciate this author’s skill for capturing the sentiment of a particular time. The reader feels all the more a confidante because Sanmao is at times unapologetically critical of the indigenous community’s traditions and behaviours she perceives to be uncivilised or barbaric, as shared in the stories of child marriage or descriptions of personal hygiene habits.

On the one hand, Stories is an account of a particular place during an historic era. It is also a deeply personal act of self-reflection by the author. She contemplates what within her led her to what many would consider a desperate environment: “I want a taste of many lives…Only then would this journey be worthwhile. Although perhaps a life plain as porridge would never be an option for me.” Her drifter lifestyle provides readers with a glimpse into a woman desperate to escape the expectations (and fear of disappointing) her parents’ post-war generation, and a man she reluctantly marries although is evidently so connected to she risks her life for him.

In our current situations, where we are contemplating our futures as we cautiously consider coming out of enforced physical isolation, it is hard not to warm to Sanmao despite her strident opinions. Like us, she is human, one moment at peace and finding beauty in the stillness of her own company, yet at others deeply fearful of what lurks in the unknown. The word ‘isolation’ arises in every chapter, like a repeated refrain in a song. A beautiful but haunting note drifting through the reader’s consciousness and presaging the author and her companion’s tragic futures – all the more haunting given that neither had insight as to what lay before them.

Reviewed by Tamara McCombe