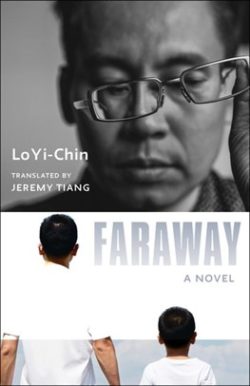

Faraway by Lo Yi-Chin

translated by Jeremy Tiang

(Columbia University Press, 2021)

Publisher's Blurb

In Taiwanese writer Lo Yi-Chin’s Faraway, a fictionalized version of the author finds himself stranded in mainland China attempting to bring his comatose father home. Lo’s father had fled decades ago, abandoning his first family to start a new life in Taiwan. After travel between the two countries becomes politically possible, he returns to visit the son he left behind, only to suffer a stroke. The middle-aged protagonist ventures to China, where he embarks on a protracted struggle with the byzantine hospital regulations while dealing with relatives he barely knows. Meanwhile, back in Taiwan, his wife is about to give birth to their second child. Isolated in a foreign country, Lo mulls over his life, dwelling on his difficult relationship with his father and how becoming a father himself has changed him.

attempting to bring his comatose father home. Lo’s father had fled decades ago, abandoning his first family to start a new life in Taiwan. After travel between the two countries becomes politically possible, he returns to visit the son he left behind, only to suffer a stroke. The middle-aged protagonist ventures to China, where he embarks on a protracted struggle with the byzantine hospital regulations while dealing with relatives he barely knows. Meanwhile, back in Taiwan, his wife is about to give birth to their second child. Isolated in a foreign country, Lo mulls over his life, dwelling on his difficult relationship with his father and how becoming a father himself has changed him.

Faraway is a powerful meditation on the nature of family and the many ways blood can both unite and divide us. Lo’s depiction of family dynamics and fraught politics contains a keen sense of irony and sensitivity to everyday absurdity. He offers a deft portrayal of the rift between China and Taiwan through an intimate view of a father-son relationship that bridges this divide. One of the most celebrated writers in Taiwan, Lo has been greatly influential throughout the Chinese-speaking world, but his work has not previously been translated into English. Jeremy Tiang’s translation captures Lo’s distinctive voice, mordant wit, and nuanced portrayal of Taiwanese culture.

Reading Chinese Network Reviews

Reviewed by Ruth Matanda, 10/3/22

This month’s book was a (moving) novel from Taiwanese author Lo Yi-Chin.

This month’s book was a (moving) novel from Taiwanese author Lo Yi-Chin.

Faraway is a semi-autobiographical novel in which Lo uses a fictionalised version of himself in order to explore the history of his family, particularly his father who fled from the Mainland to Taiwan after the loss of the Nationalist party to the Communist party following the 1949 Chinese Civil War. The book follows the life of the author’s father after fleeing, the reconstruction of his life on the island; remarrying and having a daughter and two sons, one of which we can assume is Lo himself and his eventual return to the mainland where he has a stroke. It’s the events following this which the book focuses on as it explores how Lo’s own life is impacted and ultimately changed by his father’s hospitalisation. We see Lo’s fictionalised self struggle with the rigid hospital procedures and policies, his almost non-existent relationships with estranged relatives and the constant worry he has of his wife back on the island who is due to give birth to their second child.

Whilst the premise may not sound that appealing to many, I found that Faraway is a great book which perfectly encapsulates the feeling of isolation one faces when away from home and the feeling of being a stranger in a place you should feel connected to whether due to ancestral lineage or familial ties.

Lo does a wonderful job of showing the divides that can exist within a family and how these divides shape family dynamics. His portrayal of the strained relationship between his own father can be seen as a wider socio-political commentary on the rift which exists between Taiwan and China with him and his father representing one side each, sharing similarities but also being very much different which leaves either side unable to fully understand the other.

Whilst the book can be sombre at parts as Lo is open about his vulnerabilities, whether that’s being in a country that is foreign to him or pondering on his role as a father which leads to him contemplating his relationship with his own father, I found that there was a hint of optimism and hope embedded in the story, perhaps alluding to the fact that no relationship is ever truly irreparable.

Perhaps my fondness of the book is due to my own personal experience. The novel reminded me of my time in Taiwan, the varied and nuanced perspectives which I encountered from Taiwanese people of all ages and social classes regarding the relationship between Taiwan and China. To me, this book reflects that experience by presenting a more nuanced narrative on the Taiwan-China problem and Lo does it in such a subtle way without being too on the nose or simplifying the topic. Lo manages to humanise people on both sides of the conversation and depoliticises the narrative; the book does not attempt to make readers sympathise more with one side over the other but rather highlights the flawness of humanity and the imperfections which we all have.

I had never heard of Lo before reading this novel but a quick search revealed that he is viewed as one of the most influential Taiwanese writers and this book is a perfect example of why. I was moved by this book and will surely be adding more of Lo’s work to my to-read list.

Reviewed by Ruth Matanda

Reviewed by Tamara McCombe, 10/2/22

Faraway, published in Chinese in 2003, was translated by Jeremy Tiang in 2021 and is the first full-length English translation of Lo Yi-Chin’s work. Lo fans are stunned it has taken over a decade since he first made his name on the Taiwanese literary scene for this to be the case. Due to the sentimentalist realism tradition which pervaded Taiwanese publishing before him, Lo’s tales expose the sordidness of human nature have been an exploding bombs in a flower garden. His fiction has been lavishly accoladed both in his native Taiwan and internationally.

Faraway, published in Chinese in 2003, was translated by Jeremy Tiang in 2021 and is the first full-length English translation of Lo Yi-Chin’s work. Lo fans are stunned it has taken over a decade since he first made his name on the Taiwanese literary scene for this to be the case. Due to the sentimentalist realism tradition which pervaded Taiwanese publishing before him, Lo’s tales expose the sordidness of human nature have been an exploding bombs in a flower garden. His fiction has been lavishly accoladed both in his native Taiwan and internationally.

The word “Kafkaesque” is rarely left unmentioned in any discussion of Lo’s work. Faraway is arguably his most kafkaesque to date. The dominant narrative is of Lo’s fictional struggle with bureaucracy to return his father to Taiwan for medical treatment following Lo senior suffering a stroke while visiting his home town in mainland China – Lo senior fled to Taiwan with the Kuomintang in the late 1940s. The author is embroiled with endless and circular paperwork, faceless agents on the phone and bribe taking doctors in order to secure the return of his father, mother and himself to Taiwan.

What follows this account is a hard-to-follow series of anecdotes experienced by the author in Taiwan. These anecdotes do not follow a linear progression. Instead, the connection is the author’s worsening existential crisis as his reflection blurs into that of the father and country he has no respect for. Whilst on the mainland, Lo is so consumed by the effort to get his father back to Taiwan he fails to take in much of the people and place that surround him. The reader is given a list of events and perfunctory descriptions of the environment. Only once freed from the mainland does he have the mental bandwidth to craft poetic images and realise he is “…a child of Taiwan. When I went to China as it was back then, the experience had some of the novelty and unknowing of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland.”

Laying stark in this account is that it is singularly from the male perspective. Only passing comments and opinions from Lo’s mother who shares the struggle to return Lo senior to Taiwan, Lo senior’s first wife who is confronted by the presence of her younger successor and the author’s wife who remains in Taiwan with their two year old son and facing the prospect of giving birth without her husband’s support. After all, this is a contemplation of the magnetic, attracting and repelling, forces between father and son.

This is a searingly snobbish criticism of the mainland by a Taiwanese. Lo describes the city he is trapped in as a “place where time seems to flow backwards”. This is an ungracious comment, for only in his father’s generation was China ravaged by the civil war which compelled Lo senior to abandon his first wife and son for a better life in Taiwan.

Readers will either love or loathe the author’s literary and popular culture references such as to Kafka, Hayao Miyazaki, Edvard Munch and Stephen Spielberg. Those less familiar with Chinese culture and history may find these waypoints helpful. Others may hold that a more self-confident craftsman would employ artistic inspiration without direct references. Regardless, Lo’s story is an embodiment of mainland Chinese life, burned by bureaucracy, in the early 2000s.

Reviewed by Tamara McCombe