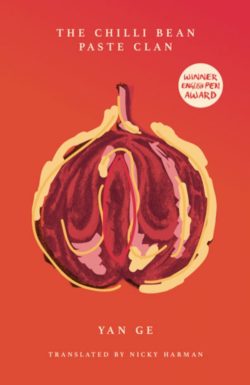

The Chilli Bean Paste Clan by Yan Ge

translated by Nicky Harman

2018, Balestier Press

Publisher's Blurb

Set in a fictional town in West China, this is the story of the Duan-Xue family, owners of the lucrative chilli bean paste factory, and their formidable matriarch. As Gran’s eightieth birthday approaches, her middle-aged children get together to make preparations. Family secrets are revealed and long-time sibling rivalries flare up with renewed vigour. As Shengqiang struggles unsuccessfully to juggle the demands of his mistress and his wife, the biggest surprises of all come from Gran herself……

Winner of English Pen Translates Award

Reading Chinese Network Reviews

Reviewed by Simona Siegel, 5/6/19

What would you do to keep your family together? That was the question that popped into my head after finishing reading this book. The Chilli Bean Paste Clan is not just another soap opera about the Chinese family, it is a very funny yet complex and deep portrait of the life of people living together, that call themselves family, but have no idea about the actions and intentions of the others.

What would you do to keep your family together? That was the question that popped into my head after finishing reading this book. The Chilli Bean Paste Clan is not just another soap opera about the Chinese family, it is a very funny yet complex and deep portrait of the life of people living together, that call themselves family, but have no idea about the actions and intentions of the others.

Nicky Harman has done an amazing job translating the book from Sichuan dialect, which must have been really hard, not only to understand the dialect but also to grasp the small differences and ideas, and translate it. While reading the book I often stopped and thought how it would have been written in the original version. Especially the character of Dad who uses interesting vocabulary for his obscenities and it made me wonder how it was written in the original version.

Reading the book, you can easily get drawn into the story and all the family business. Like a flower, the whole story opens up in front of you and the reader slowly gets to know the family members, their stories, secrets and hidden desires. However, there are lot of characters, so that the list of family members and other people at the beginning of the book with short characteristics is very useful.

There are some interesting points about the story that will make you want to read the book until the very end, even though I found some parts quite slow-paced. The fact that the narrator is a daughter that the reader never meets and never learns more about her, yet she is still present in the story, and it is left for the reader's imagination what has happened to her. Dad is the main character who connects and divides the family. He works in the chilli bean paste factory that belongs to his family. He is not happy with his life, so he seeks adventure in adultery.

All other characters are connected via Dad and influenced by his actions. The highlight of the whole story is supposed to be the huge celebration of the grandmother's 80th birthday. They are a traditional Chinese family from a rural area, where the role of each member of family is strictly decided. Yet, many things get accepted and overlooked in order to keep the family together. However, you can see how the older people get, the less they believe in those structures that bind them. Step by step, each member of the family unveils their struggles and wants to change their life, which complicates the whole story.

By this review I do not plan to spoil the story to the reader, however I must say that even though you can find some Chinese stereotypes, from the drinking parties with hostess, to a child born out of wedlock, the final climax of the story was a very refreshing surprise.

Reviewed by Simona Siegel

Reviewed by Ruth Matanda, 22/1/19

The Chilli Bean Paste Clan is a story about familial relationships and sibling rivalry told through the eyes of Duan Xingxing an omnipotent narrator about whom all we know is that she is in hospital due to a breakdown. We follow the lives of an affluent Chinese family which seems to constantly be under threat of collapsing, from the seemingly impending death of the Duan Xue family’s matriarch May Xue, to the countless extramarital affairs of Xue Shengqiang, a father, husband and, most importantly, a womanizer.

The Chilli Bean Paste Clan is a story about familial relationships and sibling rivalry told through the eyes of Duan Xingxing an omnipotent narrator about whom all we know is that she is in hospital due to a breakdown. We follow the lives of an affluent Chinese family which seems to constantly be under threat of collapsing, from the seemingly impending death of the Duan Xue family’s matriarch May Xue, to the countless extramarital affairs of Xue Shengqiang, a father, husband and, most importantly, a womanizer.

Although the voice of the story is female, we see the story unfold through a male perspective as events unfold from the perspective of Xue Shengqiang and one thing that I did notice is that events are never recounted from the perspective of a female character. However, despite the overall lack of an active female voice or that the portrayal of women is not particularly positive, from the scheming grandmother May Xue to Jasmine, Sheng Qiang’s mistress who appears to embody some of the stereotypical mistress cliches, naive and financially dependent on a man to provide for her; I do not think that the book’s portrayal of women can be considered particularly offensive or as adhering to negative social stereotypes.

In fact one thing which I took away from this book is that ambition and power are genderless as the women are as hungry for power, no matter how little, as the men in their lives and almost all of the characters lead a kind of double life to protect their secrets, everyone is lying and being lied to, there are no moral characters and Yan Ge does a wonderful job of subtly expressing the conflict the power struggle and sibling rivalry causes.

Overall, I think that the book is an amusing read which even when addressing serious issues keeps a light-hearted and humorous tone. The characters are complex, not always easy to understand or sympathise with -- an aspect which I found myself to enjoy.

I recommend the book to anyone who is interested in understanding relationship dynamics and the importance of family in China and how factors such as reputation, wealth and power can lead to the gradual collapse of a clan.

Reviewed by Ruth Matanda

Reviewed by Amy Matthewson, 26/11/18

The Chilli Bean Paste Clan follows Shengqiang, owner of a lucrative chilli bean paste factory and his relationships with his family members, friends, and lovers. The story takes a hard look at the intricacies of relationships and responsibilities within the Duan-Xue family, highlighting both the virtues and flaws of all the characters.

The Chilli Bean Paste Clan follows Shengqiang, owner of a lucrative chilli bean paste factory and his relationships with his family members, friends, and lovers. The story takes a hard look at the intricacies of relationships and responsibilities within the Duan-Xue family, highlighting both the virtues and flaws of all the characters.

The book is narrated by Shengqiang’s daughter, Xingxing, although she never makes an appearance in the story. Xingxing is in a mental hospital but has the position of omnipotent narrator and knows her father’s every thought and sexual activities. Whether the truth of her narrative is accurate is questionable since Xingxing is in a mental hospital, although this is never addressed in the book.

The book is very well written. The characters come to life so vividly that I was immersed in the unfolding events, feeling almost as if I was there, in the middle of all the drama. This was, however, not a positive experience. While there were certainly tender moments of love and support, I found the sense of obligation, control, and manipulation among the family members oppressive.

The family dynamics are farcical and humour is injected in at just the right times to relieve the tension. However, in this era of Trump and the MeToo campaign, I found it difficult to laugh away the misadventures and foibles of Shengqiang. There is much awareness of the long-term effects of sexual harassment that has been highlighted recently and the treatment of the young hostesses by the older men during the drinking engagements made me cringe.

I did not find Shengqiang to be a lovable rascal nor did I find him charming or endearing. His macho grandstanding simply wore me out. The complacency of all the characters in allowing infidelities and thoughtlessness along with reckless and hurtful behaviour to flourish made me feel exhausted. At the end of the book, I felt grateful that I was able to extricate myself from this world.

I wonder if the main purpose of The Chilli Bean Paste Clan was to challenge patriarchy or provide a nuanced story of the complexities of human nature and the societies we create. While I did not enjoy the book, I do feel that the story has a lot to offer in raising questions about morality, social and familial expectations, and what constitutes loving or abusive behaviour.

I appreciated Yan Ge’s strong writing style, ability to bring characters to life, and for not shying away from writing Shengqiang’s thoughts with as much colour as his personality. Nicky Harman did a wonderful job in translating the book.

Reviewed by Amy Matthewson

Reviewed by Stephanie Boote, 29/6/18

One of the interesting things about reading Chinese fiction is that the gender of the author is not always immediately apparent, reading The Chilli Bean Paste Clan was one of those situations for me. On first reading this book, I have to be honest, I thought the author was male and I became increasingly angry with the way it was written. The language used to describe the father figure’s treatment of women, rankled me more and more until I was furious with the author for writing it at all. However, about halfway through reading, at the pinnacle of my annoyance, I found out that Yan Ge is actually a woman. I had the pleasure of meeting Yan Ge a few weeks ago at a conference and when it became clear that I was not the only one who’d had this issue, it brought into light an interesting discussion on gender and authorship.

One of the interesting things about reading Chinese fiction is that the gender of the author is not always immediately apparent, reading The Chilli Bean Paste Clan was one of those situations for me. On first reading this book, I have to be honest, I thought the author was male and I became increasingly angry with the way it was written. The language used to describe the father figure’s treatment of women, rankled me more and more until I was furious with the author for writing it at all. However, about halfway through reading, at the pinnacle of my annoyance, I found out that Yan Ge is actually a woman. I had the pleasure of meeting Yan Ge a few weeks ago at a conference and when it became clear that I was not the only one who’d had this issue, it brought into light an interesting discussion on gender and authorship.

In The Chilli Bean Paste Clan, the most important thematic element is the oppressive family, which affects every aspect of the plot. Throughout the book Shengqiang is desperate to escape the toxic relationships that he has formed with his family, particularly with regards to his intrusive mother, his unhappy marriage and his despised older brother. Despite the many flaws of this man, it is tragic that the only family members he seems to honestly care for are separated from him. His daughter is in a mental institution, his sister lives far away and when he believes he is going to have a second child with his mistress it turns out that she has betrayed him with his driver.

Shengqiang is presented as a man who has the capacity to love but is held back by his bitterness towards the past and the people who are constant reminders of it. Try as he might to forge his own identity he is repeatedly confined by his obligations to the family. This entrapment is reinforced by his daughter, the point of view character. With the exception of being addressed by other characters, Shengqiang is only ever referred to as Dad, his literary identity is therefore unmistakably linked to his place in the family structure. His problematic behaviour and disrespectful treatment of women can thus be interpreted as an outlet for the loathing he bottles up inside.

All of the unspoken internal tension is bound to erupt and I love how Yan Ge builds tension towards this inevitability in her writing. Shengqiang’s inner monologue jarringly juxtaposes his outward shows of filial piety, and his frequent use of money to placate his family members emphasises his inability to solve problems on anything other than a surface level. When you read Shengqiang thinking something as bitter and angry as: “I spent years of my life stirring those vats, I sweated my f-----g guts out, till I finally got to sit behind that desk, and you just come and plonk your arse onto my chair!” only to read that he then “beamed a welcoming smile” and enquires about his brother’s lunch, it is clear that an extremely unhealthy amount of internal tension is being harboured.

Ultimately it is this tension which nearly kills him, suffering a heart attack in the middle of his mother’s birthday party. Throughout the book this party has been a microcosm for the personal problems of the family. A huge outward display of love and respect which masks an equally huge and seething family tension. It is at this point that at last the façade snaps and after several family secrets are revealed Shengqiang’s personal problems take their toll.

However, Shengqiang is not the narrator of this story and therefore it’s conceivable that the events may have been manipulated by his daughter. Xingxing is the only character allowed her own identity. She tells the story with an eerie omnipotence and isn’t referred to by a familial title. I asked Yan Ge if Xingxing being in a mental hospital had a particular significance, as it never influences the plot. Yan Ge asserted that the mental hospital itself was not important but it served to remove Xingxing from the immediate family and that the unreliable narrator trope was a favourite of hers.

Despite this, I can’t help but feel as though the mental institution could still be read as important to the story. Particularly as Xingxing has an uncomfortable amount of knowledge of her father’s private thoughts and doesn’t seem to flinch from graphically describing his sexual activity. Occasionally the reader is told that she knows things because her mother, aunt and grandmother have told her, but she isn’t shown to have actually ever spoken to her father about it. It is possible that the father’s perspective is completely fabricated by Xingxing herself. Having heard how her father treated the women in his life, perhaps she felt the need to justify his behaviour, to provide a story which presented him in a more nuanced light. The mental hospital adds a layer of unease to this story, her detachment and coldness while she describes events which must have been traumatising for a young child to witness, hiding an unexplored layer of personal tension for Xingxing herself. She gives no personal opinions, instead devoting her narrative to explaining her father’s story. It seems to me, that the apple doesn’t fall far from the tree and Shengqiang is not the only character hiding his internal through outward displays of filial piety.

Through her narrative Xingxing attempts to provide closure for her family which may not have been possible had the story been told by someone who was directly involved in the crisis. Her distance enables her to create a detached version of events. Unfortunately, although she is distanced from the story she is not free from the struggles of her family and I think it would’ve been extremely interesting to read perhaps an epilogue of her personal reflection on the story she had told.

In my opinion, there is one way in which the Xingxing’s opinion bleeds into the world of her narrative. Her father’s reactions to the modern world and his symbolic lack of autonomy through travel. Throughout the book Yan Ge’s characters are plagued by indifference to world around them. They haven’t noticed the world changing and suddenly it’s too late, drenching the novel in nostalgia for the past. A particularly powerful scene describes Shengqiang realising that he doesn’t recognise the majority of people on the street anymore and that he has no idea what happened to a lot of them. He has been driven about by his driver for so long that he has forgotten the personal connections he made whilst simply walking down the street. The fact that he has a driver, Zhu Cheng, is also significant as it shows him to be passive, whilst another character is in the literal and narrative driving seat. When it is discovered that Zhu Cheng has been carrying on an affair with Shengqiang’s mistress, the lack of control that Shengqiang has had over his life manifests in this betrayal.

To me it makes sense to read this lack of control as relevant to Xingxing’s experiences. Having been away from home for a long time, it is reasonable to assume that she would react to the changes of her hometown, much the same as her father is described to, with confusion and nostalgia for the past. Furthermore, the lack of personal control embodied by the character of Zhu Cheng, is highly relevant to Xingxing’s own experiences of being controlled and sent away by her family. This lack of self-determination and the pain that must have been caused, is perhaps also expressed in the descriptions of her father’s confused and devastated reactions.

Of course this is speculative, but possible due to the unreliable narrator trope. It’s certainly interesting to contemplate.

Ultimately this book is an unflinching perspective on the life of an extremely dysfunctional family. Whilst I do feel that the ending comes quite abruptly, it does establish that the family are able to form more empathetic bonds and even take more control over their own independence. As I wrote earlier I would have liked to have seen an epilogue of Xingxing’s reflection on the story, or at least more detail about her perspective, but at the end of the day this isn’t her story but that of Shengqiang.

Reviewed by Stephanie Boote

Reviewed by Henry Yunwei Wang, 27/5/18

"A family drama that manages to be both warm and funny, and barbed and irreverent", the talented author, Yan Ge's award-winning novel, which under the title of Sichuan condiment, The Chilli Bean Paste Clan《我们家》, is now available with Nicky Harman's brilliant full English translation. The whole grandiose laundry of dirty linen, with abundant usage of Sichuan dialect, especially swear words and vulgar obscenities, has its setting in a Chinese Western small town, Pingle, the literary Kingdom of Yan Ge.

"A family drama that manages to be both warm and funny, and barbed and irreverent", the talented author, Yan Ge's award-winning novel, which under the title of Sichuan condiment, The Chilli Bean Paste Clan《我们家》, is now available with Nicky Harman's brilliant full English translation. The whole grandiose laundry of dirty linen, with abundant usage of Sichuan dialect, especially swear words and vulgar obscenities, has its setting in a Chinese Western small town, Pingle, the literary Kingdom of Yan Ge.

"Serried ranks of earthenware vats, three or four feet tall and with a girth as big as two arm spans, held a bubbling mixture of broad beans which had been left to go mouldy, to which were added crushed chilli peppers and seasonings like star anise, bay leaves, and great handfuls of salt. As the days went by in the hot sunshine, the chilli peppers fermented, releasing their oil and a smell which was at first fragrant, then sour. Sometimes the sun was so strong that the brick-red paste in the vats boiled up and started to bubble." (pp.18)

With the unique smell of chilli bean paste when reading, there grows tension among the dysfunctional family’s middle-aged siblings, which was triggered by Gran’s eightieth birthday celebration. With the narratorial voice speeding up and slowing down, good dialogues, natural twists and turns, interweave and expand the characters' relationship in the nutshell. A concupiscent and rapacious chilli bean paste mill manager, the dutiful son and capable brother, the Dad, secretly hides his favourite mistress in the same mansion building as his mother and blithely cheats on his wife. A pretty wife, the Mum, who had fallen out of favour with Dad. The peacemaker Aunt and Dad’s most abhorrent elder brother do everything in vain until even, in the end, the matriarch, the icon of the family, is discovered to not really lead a virtuous clan, having had an affair with her son's supervisor old Chen and now it's the turn of her husband to "have a woman outside".

The pitch-perfect, vividly evocative descriptions of family shenanigans, somehow, are just like the process of making chilli bean paste: the stirring bar makes the beans give off liquid sounds and the flaming red chilli oil flow out, releasing an unique aroma and stink. Moreover, the smart, genuine, subtle balance contained in the flawed family relationships, is presented to be a similar mix of chaos, despair, indifference, but also with mildness, tolerance, and comprehension. It is both sides of the coin that ultimately lead the narrator and her relatives to irresistibly love their home, love their family, deeply, but also unsentimentally.

"In Dad’s cell phone, Jasmine Zhong had gone under a variety of guises, all masculine. A few months ago, she had been listed as Zhong Zhong, then for a couple of weeks, it changed to Zhong Jun; recently Dad had decided to keep life simple, and he listed her as just Zhong." (pp.14)

As the well known fact that people who live in Sichuan are born with an optimistic characteristic, also, the slangy phrases and their connotations all vividly form Yan Ge’s unexpected pen portraits: funny, ironic, relaxing, warm. The grinding hardship of life and those painful truths in everyone’s past could be compared to a worn white shirt, you may have to wash it again and again with different attitudes, but you will never be able to throw it away with ease.

Reviewed by Henry Yunwei Wang

Reviewed by Bonnie Cheung, 14/5/18

There were many different factors contributing to my enjoyment of this book which makes it somewhat difficult to pick a specific thing to begin this review with.

There were many different factors contributing to my enjoyment of this book which makes it somewhat difficult to pick a specific thing to begin this review with.

So let’s start with the external aspects of the book which we, as readers, encounter before we even delve into the lives of the characters within the wonderfully woven work.

The book cover is a splendidly bold red colour that makes it almost impossible to ignore, almost like the story itself. Not to mention the differing interpretations a reader may arrive at when confronted with the image on the front cover. While some may know that it is intended to be the shape and design of a chilli bean, I personally thought that the image was of a female organ of sorts. Since sexual interaction was a rather integral part to the plot I never considered the image to be anything else until I was told otherwise.

The next fantastic aspect of the book, which I found very helpful and thoroughly appreciated as I dove into the novel, was the list of characters summarising who they were. As more and more family members and characters were introduced to the story, there were certainly moments where I became a little lost with the transliterated names and had to refer back to the list to remind myself which character was who.

The story predominantly follows the life of the second son and current owner of the chilli bean paste factory. The book flows somewhat seamlessly between the personal thoughts of the narrator, descriptions of times gone by and mostly the events from the beginning of planning the true head of the household’s birthday up to the birthday itself and a little after that.

To say that a lot occurs during that time span would be an understatement, but to avoid accidently dropping spoilers to potential readers, I shall endeavour to keep my comments vague.

Regarding the characters, one thing I truly enjoyed was the humane and totally honest and realistic manner in which interpersonal relationships were displayed. It was fiction, and yet there were times when I had to remind myself that it was a piece of fiction. That this story wasn’t verbatim-real. The characters were relatable and nothing incomprehensibly absurd happened. The events within the book, the exchanges the characters had, the reactions they had to their give situations were completely believable.

For me, I felt that this story embodied the idea of a Chinese family, the importance of reputation and how others perceive you and your family and the estrange way a mother might display her love for her children utterly entrancing. These are all attributes prevalent in many Chinese TV dramas which centre around the theme of family.

I felt that the down-to-earth and sometimes crude language used in the dialogue were honest and true to the personalities of the characters. The effort the author must have gone to in order to give accurate portrayals of these characters through speech was evident and I often found myself falling into the story as though I was there right alongside the characters, participating in their conversations. That to me is one of the best and most important feelings to have as a reader.

I would highly recommend this book to anyone wanting to immerse themselves into a story about family and relationships. What might parents be willing to do in the name of protecting their family and its reputation? What would you be willing to do to reclaim a long-lost love?

Reviewed by Bonnie Cheung

Reviewed by Markéta Glanzová, 30/4/18

The Chilli Bean Paste Clan is a novel written by a Sichuanese writer Yan Ge. The novel was translated by Nicky Harman, whose translation is very fluent and vivid and deals well with the transformation of Sichuanese dialect into English. Nicky Harman was deservedly awarded an English Pen Award for her translation. At the very beginning of the book, there is a list of characters, which is very useful, as it makes it much easier for the reader to understand the story and the relationship between the characters right from the beginning.

The Chilli Bean Paste Clan is a novel written by a Sichuanese writer Yan Ge. The novel was translated by Nicky Harman, whose translation is very fluent and vivid and deals well with the transformation of Sichuanese dialect into English. Nicky Harman was deservedly awarded an English Pen Award for her translation. At the very beginning of the book, there is a list of characters, which is very useful, as it makes it much easier for the reader to understand the story and the relationship between the characters right from the beginning.

The Chilli Bean Paste Clan is a story about a family from Sichuan, which is built around the character of the father. However, the narrator of the story is not the father (as one could expect), instead we can explore the world of the novel through the narration of his daughter. Daughter-narrator brings a breath of fresh air into the story and sometimes makes even the tense scenes funny. She puts together stories, how they were told to her by different members of the family and make one story out of them. However, the main perspective is still of the father, and the reader can even see his thoughts, which is an interesting narration experiment considering the narrator is not the father but the daughter.

Another interesting fact considering the daughter is that she is barely present in the novel and we never learn much information about herself. One of the rare pieces of information we know is that she is in the mental institution. Which raises the question of how trustworthy she is as a narrator (not just because of her mental problems but also because she is interpreting the events, which were told to her by different people). The whole story happens in just a few days but because of lots of flashbacks of the father, we can piece together the whole story of the lives and relationships of the members of Xue-Duan family. The plot circulates around a big family celebration which the siblings organise for their mother's 80th birthday. The celebration brings the whole family together, triggers lots of emotions, and reveals secrets which were meant to stay hidden.

The main character - the father - is the owner of a well prosperous Chilli Bean Paste Company. He is explosive, enjoys drinking and the company of his friends, hates his brother and is cheating on his wife. However, he never loses his temper with grandma, and fulfils all her wishes like a filial son. The readers however have the privilege to access his head and thoughts, so we can sense that sometimes it takes dad lots of effort to behave the way he behaves. And even though he can hardly be considered a positive character, in the end it is not hard for the reader to sympathize with him.

The novel is quite male-centric as everything is focused on the father and we see the world through his perspective. It is quite common that the women are called "stupid cows." However, it would be unfair to consider the male characters in the novel bad and female good. All the characters in the novels have some secrets and no one can clearly be considered good or bad. The life the characters are living could be sometimes called immoral and the family is completely dysfunctional. However, the story doesn´t make any moralising conclusions and it is completely up to the reader to proceed with the story and make some conclusions for him or herself.

Yan Ge created very vivid characters, which are not black and white, but very complex and it would be a mistake for the reader to make fast judgements about them. Yan Ge is serving us the information about the characters piece by piece and makes us re-evaluate the picture we created about the characters every time additional information suddenly pops up. At the beginning most of the readers would probably see father as an immoral, self-centred businessman, who enjoys the company of girls, alcohol and cigarettes way too much; and his mother (the narrator´s grandmother) as a nice and loving old lady. However, as we are getting deeper into the story, we are provided with many different pieces of information (from both past and present) and a new picture of the characters suddenly appears just in front of our eyes.

Father who is a capable businessman and used to giving orders to others, is now shown as a dutiful son, who is not capable of opposing his mother his entire life, being manipulated by her (and other women in general). This also shows his mother in completely different light as a dominant person, insisting on her own truth, not willing to make any compromise. As the story continues, we are getting more familiar with the conditions in the family and the deeper we go under the surface, the clearer it becomes, that the family is far from being perfect. There are some great tensions inside, which make the reader more and more tense while waiting for the firework of emotions to explode.

Reviewed by Markéta Glanzová

Reviewed by Barry Howard, 29/4/18

Chilli bean paste is a staple ingredient of the Sichuanese kitchen, but largely unknown in the West. And just as I guess many home cooks would be unsure of what to do with it, many readers may also struggle with the book’s main character – Dad, the chilli bean paste factory owner. For me he’s a man-child. He brings energy and humour to the story, but his immaturity and irresponsibility raise questions of morality.,

Chilli bean paste is a staple ingredient of the Sichuanese kitchen, but largely unknown in the West. And just as I guess many home cooks would be unsure of what to do with it, many readers may also struggle with the book’s main character – Dad, the chilli bean paste factory owner. For me he’s a man-child. He brings energy and humour to the story, but his immaturity and irresponsibility raise questions of morality.,

We follow Dad and his day to day life as factory owner, father, husband, son and brother. Each role breathes life into him via the narration of his daughter. As an aside we never find out who the daughter is, and the wish to know more about her may disappoint but this is not a story about her. She is a vehicle to portray her father from a familiar, balanced perspective.

I read this book after just having read Yeng Pway Ngon’s Unrest. One of the characters in the book also enjoys sleeping around, but with two important differences. First, that character is challenged to consider if satisfying animal desires equates with human happiness. Second, there is a female reaction – because if women accept extra-marital affairs as ‘men being men’, how compliant are they in the endurance of a patriarchal culture Perhaps Yan Ge’s novel is a statement on how China’s societal development has lagged behind its miraculous economic advance.

Whilst reading, I recalled Zhou Daxin’s (周大新) Sesame Oil Mill (香魂女). A short story that also looks at family relationships in provincial China, post-1978, with the manufacture of a local condiment as the backdrop. Sesame Oil Mill, although written in 1995, is much more overtly feminist. Firstly, the protagonist is a married woman and mother running the family mill. Moreover, she is able to reflect on her own behavior and act radically from a position of power (rather than just abusing it fro personal gain).

By contrast The Chilli Bean Paste Clan is far subtler and so risks leaving readers behind, especially those unfamiliar with China. It’s like dry British humour, when a straight-faced spoken comment delivered with deadly seriousness can have one person earnestly nodding and another cracking up.

And this is a book dependent on humour. At times I found the story slow-moving, but just before it might get boring Dad had me laughing out loud. As a man, you can imagine enjoying his company on an evening out with colleagues or peers. Wit brings you closer to the character, making it less simple to cast him aside as some kind of pantomime villain.

For me, the author challenges the reader to question the patriarchal societies we live in and how we respond to their complexities. Nobody is perfect, we all make mistakes. However, to what extent to we allow, say, infidelity and recklessness to be compensated by for by gregariousness and personal charm? Why might some excuse Dad’s behaviour because at least he wasn’t trying to deny his flaws? And why would we almost certainly react differently in the protagonist was a middle-aged woman instead of a middle-aged man?

Reviewed by Barry Howard

Reviewed by Zahra Raja, 29/4/18

The Chilli Bean Paste Clan tells the story of the Duan family who are a wealthy family and owners of the local chilli-bean paste factory. Set in a fictional town in Sichuan, it has all the makings of a good television drama; a scheming matriarch, an unmarried older brother who has never stopped pining after his first (said scheming matriarch disapproved), an older sister who was married off to a man of higher ranking to improve the family’s standing whom she is now determined to divorce, a younger son (our protagonist) whose fierce rivalry with his brother accounts for much of the comic tension in the book (not to mention his attempts to juggle his wife and mistress whilst attempting to throw his mother an 80th birthday party), an older son who pines over his childhood love, the daughter of the younger son who is apparently in a mental hospital and never makes an appearance herself but is perfectly able to narrate the events of the book and the wife of the younger son who puts up with her husband’s philandering ways because she may well have a lot to lose if she doesn’t (this being a mysterious inheritance). This is by no means an exhaustive list; however, it gives you an idea of just how intricately the plot and its characters are weaved together to make for a colourful, hilarious and often thought-provoking read.

The Chilli Bean Paste Clan tells the story of the Duan family who are a wealthy family and owners of the local chilli-bean paste factory. Set in a fictional town in Sichuan, it has all the makings of a good television drama; a scheming matriarch, an unmarried older brother who has never stopped pining after his first (said scheming matriarch disapproved), an older sister who was married off to a man of higher ranking to improve the family’s standing whom she is now determined to divorce, a younger son (our protagonist) whose fierce rivalry with his brother accounts for much of the comic tension in the book (not to mention his attempts to juggle his wife and mistress whilst attempting to throw his mother an 80th birthday party), an older son who pines over his childhood love, the daughter of the younger son who is apparently in a mental hospital and never makes an appearance herself but is perfectly able to narrate the events of the book and the wife of the younger son who puts up with her husband’s philandering ways because she may well have a lot to lose if she doesn’t (this being a mysterious inheritance). This is by no means an exhaustive list; however, it gives you an idea of just how intricately the plot and its characters are weaved together to make for a colourful, hilarious and often thought-provoking read.

Shengqiang, the youngest son in the family and our protagonist undeniably possesses all the characteristics that should render him unlikeable; boorish with a love for drink, foul-mouthed, thinks nothing of having a mistress and even installs her in the same building as his mother on the floor above. However, we see that despite his many(!) flaws he is not a bad man, to which even his long-suffering wife will admit. He is a filial son despite his mother’s own overbearing and occasionally cruel nature, generous to those he considers his responsibility (often more than they deserve) and respectful to and adoring of his elder sister. His squabbles and petty competitiveness with his elder brother for their mother’s affections will be relatable to anyone with siblings; however, one of the most positive character traits he possesses is his ability to forgive and forgo grudges. These positive traits are not enough to prevent him from getting into frequent trouble, however he always seems to get away with it and overwhelmingly remains a sympathetic character.

As the novel builds up to the climax, we discover the truth of the elusive inheritance, Gran’s carefully constructed image is shaken and an ambulance is required, in true ridiculous fashion. Ridiculous is really the best word to describe the events of this novel and the characters in it, however the use of ‘ridiculous’ is meant in the sense of hilarious ridiculousness rather than its negative counterpart. The narrator also gives us a snapshot into a much calmer future where the respective family members attain their innermost desires and co-exist harmoniously (harmoniously being used in the loosest sense here).

One point of interest is the narrator, Shengqiang’s daughter, who during the timeframe in which the novel is set lives in a mental hospital. We learn very little about her and she never makes a physical appearance; she deliberately remains distant from the story as to not draw attention to herself, and perhaps to showcase some objectivity. All we know is that she has attempted to piece together and make sense of the events leading up to her grandmother’s 80th birthday, though arguably as a narrator she will never be able to record her father’s story without bias (especially considering how sympathetic a character he turned out to be).

The translator, Nicky Harman, did a brilliant job in her translation; I particularly appreciated her choice of which words she kept in Chinese and which she translated to English; for example, Shengqiang often shouts ‘Ai-ya!’ before making an exclamation, and the equivalent translation ‘Good heavens!’ just doesn’t roll off the tongue as well, nor does it fit his character. Little details like this are what really bring the book to life and put flesh to the characters. The story was ridiculous and brilliant, and I will be looking to read more of Yan Ge’s work!

Reviewed by Zahra Raja

Reviewed by Vicki Leigh, 29/4/18

Sometimes you just need a bit of time and considerable distance from a situation in order to write about it, as Dublin-based Yan Ge lays out in her newly translated novel The Chilli Bean Paste Clan. Built around tales in her own backyard, nostalgia meets much drama in this story confined to the ‘four street town’ of Pingle that she states herself that she could not have written if she was still in China.

Sometimes you just need a bit of time and considerable distance from a situation in order to write about it, as Dublin-based Yan Ge lays out in her newly translated novel The Chilli Bean Paste Clan. Built around tales in her own backyard, nostalgia meets much drama in this story confined to the ‘four street town’ of Pingle that she states herself that she could not have written if she was still in China.

Aesthetically speaking, I wasn’t sure if I just have a corrupted mind, or if the front cover was being anatomically suggestive... I found out it was indeed discreetly suggesting something quite early on! Not the kind of cover you want to be reading from when you’re squished up nose to nose with a fellow commuter on the morning train!

However, once the reader gets past the subtly risqué front cover visuals, there is much to discover in this Sichuanese one-horse-town.

Our narrator is Duan Yixing (Xingxing), who the reader never directly meets. Xingxing has had some kind of breakdown that we never truly find out the reason for, but she hints at her family drama succinctly from the opening pages. Xingxing is the narrator, but it is her father Shenqiang who appears to be the true protagonist even though Xingxing is the omnipotent ‘all seeing eye’ of the novel. Dialogue such as ‘How’s Xingxing been lately?’ do make the reader feel like possibly they have accidentally interrupted a private conversation half-way through, however this does add to the layering of this family’s intertwining lives, and ensuing commotion.

Shengqiang leads a bachelor’s life of debauchery whilst married to Anqin, and elements of the heterosexual male gaze are evident throughout. He sums up his shallow misogyny in a terse manner when his eyes happen to fall upon a prior female acquaintance, and surmises ‘that was the thing with women, they got old, fat, and sallow, their looks blasted away’, and this is not even to mention his persistent use of prostitutes (even the same one as his brother! Eww.) This is also a man who enjoys yelling ‘stupid cow!’ during intercourse with his mistress Jasmine, much like in the manner of his father. Charmed, I’m sure.

Comedy ensues at various points, because even a family full of tension, jealousy and nervous breakdowns has to have its comic relief at some point. Shenqiang’s sexual awakening over a vat of chilli oil in his youth is certainly a memorable image in the mind’s eye, and I wonder how that would be pulled off as a movie scene. Later, Shenqiang gets uncharacteristically sentimental, reminiscing on the early honeymoon romance with Anqin, which is poetically written… then suddenly quips his ‘pecker was as dead as a dodo’! Wonderful!

It all takes a histrionic turning point in the final act: slanging matches, long-held secrets bubbling up to the surface, divorces, heart attacks at family parties and all that. Nice to know that even thousands of miles away from Europe, even people in China endure dysfunctional family units too, despite all the rigid Confucian ideals held dear by most. I almost felt like an embarrassed guest at the party, cringing through all the arguing!

Nostalgic yearning for the past within China’s modern juggernaut of the past 30 years or so is explored: ‘Now the [street-food] sellers are white masked and gloved’. Health and safety in China, really? Shenqiang muses that ‘no dirt roads are left in Pingle Town’ after the year 2000, as modernisation truly takes over, and the stalls and pushcarts were driven out, like most good things in the name of ‘Communism with Chinese characteristics’.

In terms of translation, Nicky Harman has done a wonderful job, even if there is a little inconsistency detected between US and UK English: ‘…talks more baloney than a bargirl’ in virtually American English, only to read later on British vocabulary such as ‘little git’. I also wondered unnecessarily what ‘jiuxiang bugs’ were, which I believe could possibly be translated as ‘stinkbugs’, and I also have yet to fully fathom why Aunt Coral’s name is the only name translated into English.

The translation of the title is also intriguing: in other languages we have An Explosive Family in French, and My Dad’s Women in German, however the English title lends a more mysterious, less ‘soap opera-ish’ smokescreen in to the Xue/Duan household’s affairs, which works well.

All in all, an amusing family drama, which was clearly a labour of love for Yan Ge. Through her self-confessed ‘pain and self-loathing’ comes a subtly life-affirming novel which reflects that you can cross all the borders in the world and still find manipulative grandmothers, deep-seated sibling rivalry, and Jeremy Kyle-style showdowns!

Reviewed by Vicki Leigh

Reviewed by Andreea Chirita, 26/4/18

There’s a strong sense of cynicism and rage on behalf of the first person narrator of this novel, Xingxing, who displays nonchalantly the most perverted and intimate instances concerning her defective family life. Xingxing voyeuristically follows the saga of her father’s carpe diem lifestyle, replete with affairs, alcohol, infatuation with money and a healthy predisposition to vulgarity. Xue Shengqiang is also the owner of a chili bean paste factory in Sichuanese village, namely Pingle Town. His high-brow position is granted to him by no one else than his own controlling mother, or ‘Gran’, who is obsessed, in a most Confucian manner, with social status. Gran’s authoritative forces are unleashed in full display around the preparation of her 80’s birthday, when every member of the family, caught up within her oppressive energies, come along with a bunch of debilitating secrets that rock their troubled lives.

There’s a strong sense of cynicism and rage on behalf of the first person narrator of this novel, Xingxing, who displays nonchalantly the most perverted and intimate instances concerning her defective family life. Xingxing voyeuristically follows the saga of her father’s carpe diem lifestyle, replete with affairs, alcohol, infatuation with money and a healthy predisposition to vulgarity. Xue Shengqiang is also the owner of a chili bean paste factory in Sichuanese village, namely Pingle Town. His high-brow position is granted to him by no one else than his own controlling mother, or ‘Gran’, who is obsessed, in a most Confucian manner, with social status. Gran’s authoritative forces are unleashed in full display around the preparation of her 80’s birthday, when every member of the family, caught up within her oppressive energies, come along with a bunch of debilitating secrets that rock their troubled lives.

Xue Shengqiang changes mistresses with enviable rapidity and natural flair, while his brother, a university professor, is frustrating his mother to extremes, for not being able to get a wife at a respectable age. Their sister is caught in continuous masochistic attempts to divorce her husband, while the narrator’s mother blissfully ignores her husband’s rampant transgressions: “Mum knows all about his affair but says not a word. She goes to work, she plays mah-jong, she reads her novels like a dutiful daughter and when she wants to go shopping, she uses dad’s credit cards. No one gossips about them, because, after all, she is the only woman in Pingle Town, who is fortunate enough to have found a husband as rich and as generous as Dad.”

Almost everyone is cheating and is being cheated in this family novel, even the elderly are no exception.

However, author Yan Ge doesn’t make a fuss around the characters’ utter lack of morality. After all, this is the typical story of any affluent Chinese family, caught in the economic turmoil that characterized the 90’s post-Deng economic reforms and the social alienation and ethical breakdown that came along with prosperity. Abnormality is the norm. Sarcasm and cutting irony are thus the key for narrator Xingxing to approach the adultery, the lies and unsolved childhood frustrations of her family members. She summarizes her dad’s life in one simple paragraph that accounts for her cold, sharp and emotionally detached look into his promiscuous life: “As far as Dad was concerned, marrying Mum was a milestone in his life, getting together with Jasmine was another, turning forty was yet another. He was not sure when it happened but at some point he made up his mind to turn over a new leaf and become a reformed character.”

A strange sense and voyeuristic pleasure in the narrator’s account of her father’s straying go beyond mere fury against his illicit double life. She delves into the emotional needs of mistress Jasmine and her loving care for her father with pure tenderness, which I find rather distressing: “Jasmine looked up and leaned her head against Dad’s shoulder. She looked endearingly vulnerable and Dad felt overwhelmed with frustrated desire”. The same incisive naturalistic feeling flabbergasts the reader in the following passage, when another mistress, Baby Girl, teaches Dad how to contain, for better lasting results, his sexual energy. After he learns the few tricks needed “to slowing down” such matters, the narrative voice of his daughter takes over and explains dad’s consequent erotic self-control endeavors with tremendous irony and spectacular cynicism: “Once he learned the knack, he never spilt a drop along the way. In any moment of crisis, when he was having sex (…) he liked to switch his mind to something completely different for a moment, before carrying on as before, delivering the goods with the girl (…)”

The colorful dialogues and Dad’s very frequent interior monologues are also satiated with semi-obscene language. Translator Nicky Harman does a wise job by capturing their local rudeness not by foreignizing the text, but by transferring into English that unmistakable touch of male machoism displayed by most of the contemporary Chinese male authors. Yan Ge consciously tried to conceal her female writer identity by recomposing, with astonishing genuineness, the grotesque farcical expression of Sichuanese cocky slang. Xue Shengqiang is pervasively jealous of his brother whom he erroneously considers to be favored by Gran, to the extent that “even his farts smell sweet”. His Freudian frustrations caused by the sick relation with his domineering mum slip out every now and then in a most straightforward, unrestrained and colorful fashion: “‘Fuck your mother!’ As soon as the words were out, he felt better. He stood over the sink, repeating obsessively: ‘Fuck your mother, I fuck your mother, I fuck your whole family!’ Strangely, it gave him a pleasurable tingling feeling down there, almost as if he wanted to pee, but different.”

As a reader you may feel that the narrative is scattered and lacking focus. Yet, seen through the eyes of a mentally disabled and rebel youngster like Xingxing, it’s only natural that her family’s petty whereabouts can’t make much sense. Her thoughts and recollections are rambling and they mirror her family’s messy conduct. In fact, by the end of the novel, you may realize that the only lucid mind within the narrative is, paradoxically, that of Xingxing. And a lucid mind can only rise above people and display, both caustically and affectionately, their frivolous day-to-day neurosis.

Reviewed by Andreea Chirita

Reviewed by Tamara McCombe, 13/4/18

Author Yan Ge is part of the 八零后 (bālínghòu) generation, the generation, especially young urbanites, born between 1980 and 1989 in Mainland China. Growing up in modern China, in an environment of tremendous economic growth and social change, this generation has been characterized by its optimism for the future, newfound excitement for consumerism and entrepreneurship. In contrast, their parents lived during the Mao Zedong era, experienced famine and political instability and lacked proper education because of the policies set forth under the Cultural Revolution. It is this generational disparity that Yan cynically mocks, illuminating important questions about China's future and its morals.

Author Yan Ge is part of the 八零后 (bālínghòu) generation, the generation, especially young urbanites, born between 1980 and 1989 in Mainland China. Growing up in modern China, in an environment of tremendous economic growth and social change, this generation has been characterized by its optimism for the future, newfound excitement for consumerism and entrepreneurship. In contrast, their parents lived during the Mao Zedong era, experienced famine and political instability and lacked proper education because of the policies set forth under the Cultural Revolution. It is this generational disparity that Yan cynically mocks, illuminating important questions about China's future and its morals.

The Chilli Bean Paste Clan is a sneering and farcical novel concerning the Duan-Xue family, owners of a lucrative chilli bean paste factory and led by a formidable matriarch grandmother who is infatuated with maintaining the family’s face. This concern for face, and maintaining wealth, becomes more and more ironic as each family member’s sordid truth is gradually exposed when grandmother’s children reunite in their hometown to host her an ostentatious eightieth birthday celebration. The pervasive importance hung on face by the Duan-Xues and in Chinese culture is symbolised by the fact Gran is celebrating her 80th birthday. In Chinese culture the number eight symbolises longevity and is pronounced similarly to 发 (fā) meaning ‘to expand’, as in ‘to expand in wealth’ (发 财 fācái).Yan mocks this small town obsession with face, family and wealth right from the novel’s beginning:

“In Dad’s cell phone, Gran was listed as ‘Mother’. From time to time, ‘Mother’ popped up on the screen at peculiarly inappropriate moments. Sometimes it would be during a meeting at the factory…Or when Dad was out drinking with friends…Or, worse still, Dad would be in bed, either with Mom or else some young woman of his acquaintance and, just when things were hotting up, A Sprig of Jasmine would ring out. Dad would feel himself going soft and, when his cell phone proved incontrovertibly that it was Gran, all the fight would go out of him…, he’d pick up the phone, walk out into the corridor, clear his throat and respond: ‘Yes, Mother’.”

Yan Ge’s writing is full of acute comments on human and inter-generational relationships, starkly made through the asides of Shengxiang (representative of the Maoist generation), or ‘Dad’ as the narrator refers to him, and through the commentary of the narrator (representative of the bālínghòu generation). This family saga yields traces of Jonathan Franzen’s ‘Corrections’ - Yan has mentioned in interviews that she became intensely influenced by Franzen’s work whilst a visiting scholar at Duke University. Having grown up in Sichuan and been a long-term resident in the West - Yan currently lives in Dublin and was resident author at the Cross Border Festival as well as having studied in the USA - she is of a generation who is able to view her mother country with the perspective that comes from having distanced herself both physically and psychologically.

Like many translated Chinese novels, Yan provides her text with a foreword. Rather than being a brief biography or polemic like so many Chinese novels in translation contain, hers was an amusing self-deprecating explanation of her writing journey and style. It was a promising start to a book that ultimately disappointed.

For all its interesting observations - the story and characters were the ingredients for a tense and gripping tale - it failed to hook me. Splitting the narration between a mentally disturbed daughter who plays no role in the story who speaks in the first person and the lead protagonist speaking in the third person meant that as a reader I neither became involved with the characters emotionally nor able to observe them from a distance. Is the third person narrator a critical metaphor for the generations after the Maoist era who idolise consumerism and technology? Is the presence of the disturbed first person narrator used to highlight the sins and sexual misdemeanours of elders, a symbol repeated in the prevalence of her uncle’s physical deformity?

Although I personally failed to engage with The Chilli Bean Paste Clan I certainly appreciate the intimate creative partnership between the author and translator Nicky Harman. Yan has drawn comment from Chinese critics for her use of dialect and crude language in her work, rarely can either be directly translated on account of cultural connotations. Fortunately for Harman she was working with an author who has an excellent grasp of English so they could clarify meaning before settling on the translation. Yet for all their hard work some of the choices of translations grated on me. For instance, when referring to each other, author and translator have the men call each other ‘bro’. Although close friends in China refer to each other as ‘brother’, ‘sister’, ‘aunt’ etc this use of the vernacular sits awkwardly with me. It is too much of an Americanism and the middle-aged characters, brought up during the cultural desert in terms of international culture that was the Mao era, are too old to have been exposed to this American show of bonhomie.

Another issue which really distracted me from the novel, which is particular to this edition of the translation from Balestier Press were the numerous typos. These are clearly not the fault of either the author or translator but nonetheless incredibly distracting.

Yan Ge’s writing has garnered prestigious praise. People’s Literature magazine recently chose her as one of China’s twenty future literary masters, and in 2012 she was chosen as Best New Writer by the prestigious Chinese Literature Media Prize. Going by The Chilli Bean Paste Clan alone, Yan shows great promise as a cross-border author, but has still yet to refine her style for maximum impact.

Reviewed by Tamara McCombe

Reviewed by Andy Thomas, 3/4/18

This translation subtly shifts the title from the blank Our Family 我们家 to a title which, if innocent, reminds me only of Alexander McColl Smith, but otherwise introduces, from eating bean paste, eating bean curd (keywords here), especially in the cover picture. The more explicit “c-word” is introduced early to make the point. So I began by looking for patriarchy, oppression, prudery and desire, and relationships with women.

This translation subtly shifts the title from the blank Our Family 我们家 to a title which, if innocent, reminds me only of Alexander McColl Smith, but otherwise introduces, from eating bean paste, eating bean curd (keywords here), especially in the cover picture. The more explicit “c-word” is introduced early to make the point. So I began by looking for patriarchy, oppression, prudery and desire, and relationships with women.

I found desire, but certainly neither patriarchy nor prudery, and a straight heterosexual story line. This is a family bedroom farce narrated by daughter Xingxing, who, we are told, suffers from an unexplained psychiatric malady. Sex runs like chilli oil in this family, where infidelity is their way of life, and the membership ebbs and flows. Established episodes of Chinese history, from Liberation through the Cultural Revolution to the business reforms and changes of the 1980s and 1990s, are scattered like used condoms through this narrative of the family under the matriarch known as Gran. It is her eightieth birthday party which serves as the breathless climax of this novel.

This family’s policy is to alternate the surnames of Gran (Xue) and Grandad (Duan) for their progeny, which suddenly becomes highly relevant to Xingxing’s Dad, Shengqiang, the hero of this novel, if indeed he is a hero. But he reflects that “We men are like the rolling, rebellious waters of the Yangtse River in angry spate. We can get into earth-shaking fights with our womenfolk, we can tear the house half-down but, when push comes to shove, those surging waters have got to subside and flow meekly into the ocean.” It is of course the love of good women which controls the flow, and Dad knows it.

In its casual references to the Party, Red Flag limousines, Dad’s liberal interpretation of the single-child policy, death and ancestors, male drinking parties with hostesses (known as “business dinners”), brothels, new apartment blocks and honorific family titles, this is a very Chinese novel, preserved with Chinese names in an elegant translation by Nicky Harman. I loved the description: “The bridegroom getting out of the Jeep looked like a Kuomintang spy”. But its message is universal. As Gran comments, “…the closer people are to you, the more easily they can hurt you, and the more you have to mind your back…No one is true to you the way your family is true to you, no one.”

And of course the food. It’s not all rice wine, beer and cigarettes, but white rice porridge and fried dough sticks for breakfast, and then chilli bean paste, of course, fish balls, fat pieces of beef, rack of rabbit, cubes of duck’s blood, pig’s arteries, all pop into the pot. Eating dumplings will never be the same again for me after a reference to chilli dumplings that could serve by allegory to sum up this novel, “Sugar sweetened the numbing heat of the Sichuan peppers.” This is a family in heat, but Gran serves the sugar.

Reviewed by Andy Thomas

Reviewed by Kate Costello, 29/3/18

The Chilli Bean Paste Clan is the perfect choice for anyone looking for a lively read. This raucous depiction of the life of the Duan-Xue family centers around chilli bean paste factory head Xue Shengqiang. Yan Ge’s endearing if not entirely sympathetic characters grab you from the first page. Shengqiang is delightfully dysfunctional from the very moment we lay eyes on him. He is a rare literary figure that manages to tear at our heartstrings even while we look down on his reprehensible behavior and laugh at his vanity. Our perverse hero curses, womanizes, schemes, and never manages to find his way to the moral high-ground. Despite his impossible personality and atrocious behavior, Shengqiang’s vulnerability and pure oafishness somehow quell our righteous indignation.

The Chilli Bean Paste Clan is the perfect choice for anyone looking for a lively read. This raucous depiction of the life of the Duan-Xue family centers around chilli bean paste factory head Xue Shengqiang. Yan Ge’s endearing if not entirely sympathetic characters grab you from the first page. Shengqiang is delightfully dysfunctional from the very moment we lay eyes on him. He is a rare literary figure that manages to tear at our heartstrings even while we look down on his reprehensible behavior and laugh at his vanity. Our perverse hero curses, womanizes, schemes, and never manages to find his way to the moral high-ground. Despite his impossible personality and atrocious behavior, Shengqiang’s vulnerability and pure oafishness somehow quell our righteous indignation.

Disguised behind the stories of conniving characters and their wanton excess lies a tender portrayal of family relationships, from bitter sibling rivalries and jealousy to care and love. The boisterous inhabitants of Pingle town weave a web of deceit and deception. They mislead and are misunderstood, but beyond all the scheming and slinking around lies a common sense of humanity. The characters, however clever they think they are, all get to play the fool. No one is spared in this farce, not Shengqiang, not his wife Anqin, and not even Gran.

This puts the reader in an awkward position. Characters are seldom redeemed completely, and they often don’t mature as much as they get further embroiled in their own foibles. Yet I’d encourage potential readers to jump in and enjoy the ride. The Chilli Bean Paste Clan gives us an opportunity to suspend our judgement and relish in the characters’ idiosyncrasies and delectably bad decisions, savor the inopportune consequences of their misguided pride, and take pleasure in their flaws. There is something strangely relatable about Duan-Xue family, one that leaves the reader in a state of introspection.

But this is no moralizing tale. The Chilli Bean Paste Clan pulls no punches, its richly interwoven narrative and exuberant language resulting in a tremendously entertaining read. Yan Ge’s boisterous portrayal of the Duan-Xue family is enriched by a smattering of foul language, from Shengqiang’s penchant for cussing in the bedroom to shrieks of rage at being upstaged by his elder brother. The Chilli Bean Paste Clan negotiates a delicate balance between pleasantly foul and over-indulgent, landing resonantly on the side of the unabashedly comical.

Yan Ge’s colorful Sichuan colloquialisms retain their punch in Nicky Harman’s masterful translation. For any potential reader on the fence, a small peek at Nicky’s translation on the monthly bookclub will do the trick. Nicky’s lively English is tremendously enjoyable, and should be commended for inventiveness in rendering Yan Ge’s ribald humor into a woefully ‘less curse rich’ language.

With Balestier’s publication of The Chilli Bean Paste Clan, Pingle joins the ranks of Mo Yan’s Gaomi township and Han Shaogong’s Maqiao. English readers will enjoy Yan Ge’s frenetic energy in narrating the all too common occurrences of jealousy, posturing, nagging sibling rivalries and romantic relationships gone stale. Yan Ge’s compassionate attitude towards her characters allows us as readers to forgive her characters without glorifying their shortcomings. The Chilli Bean Paste Clan is sharply satirical without being bitter, an exuberant addition to the growing body of novels translated from Chinese.

Reviewed by Kate Costello

Reviewed by Hsiu-chih Sheu, 20/3/18

The Chilli Bean Paste Clan, written by Yan Ge, is a family story set in a small town in Sichuan province, China. When China’s open-door policy started in the 80s, life in the small town changed dramatically. The story features a younger generation of the family as omniscient narrators, which give reader a taste of insider secret to the family’s ups and downs. The Xue family, with its chilli bean paste factory, has moved from rags to riches, and they owe their success mainly to the foresight of their grandma. The story centres on the preparation of a big birthday party for the grandma in a town full of chilli aroma. The grandma that used to play a key role in the success of the family business has now retired, but still occupies a prominent position in the family, in a parallel with the grandma of the “Dream of the Red Chamber.” The matriarch, who anchored the family, kept it together and planed for their future, has become despondent when the course of life ran against her plans.

The Chilli Bean Paste Clan, written by Yan Ge, is a family story set in a small town in Sichuan province, China. When China’s open-door policy started in the 80s, life in the small town changed dramatically. The story features a younger generation of the family as omniscient narrators, which give reader a taste of insider secret to the family’s ups and downs. The Xue family, with its chilli bean paste factory, has moved from rags to riches, and they owe their success mainly to the foresight of their grandma. The story centres on the preparation of a big birthday party for the grandma in a town full of chilli aroma. The grandma that used to play a key role in the success of the family business has now retired, but still occupies a prominent position in the family, in a parallel with the grandma of the “Dream of the Red Chamber.” The matriarch, who anchored the family, kept it together and planed for their future, has become despondent when the course of life ran against her plans.

Shengqiang, the dad of the narrator, is the main protagonist of the story. Now in his 40s, Shengqiang is a successful man running the family business and happily juggling his wife and mistress. All the hardship of his early years as a young apprentice in the factory stirring the vat of chilli bean paste has been relegated to the past. Financial success has made Shengqiang a skirt chaser. He needs a woman to satisfy his physical need and boost his confidence. His life as a factory manager is almost perfect, except when his brother is around. His older brother, Zhiming, has been a pain and has tormented him all his life. Shengqiang has never get over the fact that he had to endure the tough life of an apprentice, while his older brother, Zhiming, is allowed to go to the university.

Zhiming, the older brother, is now a professor who has been the pride of the family and the apple of his mother’s eye. Unlike Shengqiang who is the tomcat on a hot tin roof, Zhiming, looks like a cat asleep. In his 40s, Zhiming is still a bachelor. As a young man, Zhiming was forced by his mother to break up with his sweetheart in order to pursue his academic success. Obedient he was, but distraught. Now as a mature man and a dutiful son, he is home to take charge of his mother’s 80-birthday party and meanwhile secretly orchestrates a big surprise to shock the family. He intends to reclaim what he has missed as a young man.

The sibling rivalry intertwines through the whole story, along with the everyday fighting and reconciliation between husband and wife, mother and sons, mistress and wife. The portrait of a life in a small town is lively and colourful. The English translation reproduces the experience that a Chinese speaker would have had with the original Chinese text. With the use of colloquialism and slang, Nicky Harman catches the spirit of story set in a small town and vividly conjures up the lively voice of the main protagonists. This is an ordinary middle-aged man in a small town, far away from having a refined taste, but full of life and full of ideas to enjoy his life. Readers may not identify with him, but are likely to have a laugh with him.

Reviewed by Hsiu-chih Sheu