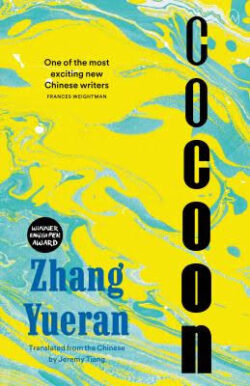

Cocoon, by Zhang Yueran

translated by Jeremy Tiang

(World Editions, 2023)

Publisher's Blurb

Cheng Gong and Li Jiaqi grew up together in a Chinese provincial capital in the 1980s. Now, many years later, the childhood friends reunite and are determined to follow the tracks of their grandparents' generation to the heart of a mystery. What exactly happened during that rainy night in 1967 in the abandoned water tower?

Reading Chinese Network Reviews

Reviewed by Catherine Shipley, 15/7/23

One way in which I consider my feelings about a novel is by noticing the thoughts and images that linger in my mind days or weeks after reading it; when I am immersed in the routines of day-to-day life and am suddenly faced with a vivid scene from the novel, unexpectedly. In the case of Cocoon these images and snippets from the story were largely unsettling ones. I think I was still trying to make sense of what I had read which, although fictional, left me with the distinctive feeling of it having been based on factual events.

One way in which I consider my feelings about a novel is by noticing the thoughts and images that linger in my mind days or weeks after reading it; when I am immersed in the routines of day-to-day life and am suddenly faced with a vivid scene from the novel, unexpectedly. In the case of Cocoon these images and snippets from the story were largely unsettling ones. I think I was still trying to make sense of what I had read which, although fictional, left me with the distinctive feeling of it having been based on factual events.

The story is recounted by two narrators, Li Jiaqi and Cheng Gong. Initially, I found this quite confusing. Li Jiaqi and Cheng Gong are friends who have been apart for a long time and come together to try to make sense of their past. They grew up at a time when, although the Cultural Revolution was over, the heavy toll it took on society was ever-present. One of the main examples of this is in the form of Cheng Gong’s grandfather. He was left in a vegetative state following a ‘Struggle Session’ in which he was physically attacked. He was kept alive by nurses in a hospital room but he was otherwise largely abandoned by his family.

Cheng Gong’s Granny’s attitude is that his grandfather should ‘hurry up and die.’ Cheng Gong’s Auntie does not want to contemplate the possibility of him waking up some day, since she has a job in the hospital which she believes she would lose were Grandad to regain consciousness. Cheng Gong appears to try to make sense of what Grandad’s existence should mean to him, moving between the callous approach of his female relatives to something more empathetic. Of course, it is impossible for Cheng Gong to make sense of his grandfather’s existence when he does not understand the circumstances leading to his grandfather’s death. At one point, Cheng Gong imagines his grandfather entered his vegetative state due to brave actions as a Communist Party member, representing the best interests of the party. He finds this brings him much popularity until someone reveals the truth.

Such trauma forms the foundation on which Cheng Gong and Li Jiaqi go about their lives. They play in an abandoned water tower, known as ‘Dead Man’s Tower,’ among corpses of criminals that are dumped there regularly by the father of a mutual friend. The human remains are used by local universities in dissection classes. Cheng Gong makes the point that even in death ‘they’ can always come and gouge something out of your remains. It leaves the impression that nothing is sacred. One might hope that there would at least be peace or respect for the individual in death but it is not the case. Although the young friends appear to accept their surroundings as normal, Li Jiaqi insists that someone will care about the memories of the dead in the future, indicating that there may be some hope of resisting ambivalence towards such horrors.

Another disturbing event concerned Cheng Gong’s relationship with his mother. She clearly adored him and treated him with the tenderness one would expect of a loving mother towards her child. She was the victim of her husband’s physical abuse, his aggression appearing to have developed during his teenage experiences as a Red Guard in the Cultural Revolution. The violence initially appears to lead Cheng Gong’s mother to seek refuge in her relationship with her son but eventually she abandons him completely. The way this part of the narrative is described is such a shock to read and deeply moving. It is yet another indicator of the deep psychological harm the Cultural Revolution caused and continued to cause to people and their relationships, long after the events themselves had finished.

The lasting impression that I had from the book was of many incidents of casual cruelty, between one person and another, particularly between those who should otherwise have been close and should have had the most loving and supportive of relationships. Nothing appears to be meaningful. People seem emotionally vacant. Their focus is on survival and navigating harsh practicalities. Their human spirit appears to be suppressed, crushed by the weight of recent history. Life goes on but as a functional, almost mechanical act, similarly to how Grandad remains alive. The hope in the novel is the two friends that seek to make sense of the past. The very attempt to consider the past and why things happened the way they did is an act of resistance and a hope that society will not be irreparably damaged by past events.

Reviewed by Catherine Shipley

Reviewed by Mia Chen Ma, 28/6/23

“She’s living for Grandpa and the rest of the clan. They’ve bound her like that retainer she wears, molding her into shape. Even as an adult, she doesn’t dare take it off in case any gaps appear. No gaps between her teeth. No freedom.” (Zhang, Cocoon, p.32)

“She’s living for Grandpa and the rest of the clan. They’ve bound her like that retainer she wears, molding her into shape. Even as an adult, she doesn’t dare take it off in case any gaps appear. No gaps between her teeth. No freedom.” (Zhang, Cocoon, p.32)

Zhang Yueran's novel, Cocoon, is a thought-provoking exploration that delves into the intricacies of a real-life incident from the Cultural Revolution. Based on a story recounted by her father, the book revolves around a neighbor who falls victim to a brutal attack during that tumultuous period and is left in a vegetative state. The discovery of a strategically placed nail embedded in his forehead adds a chilling layer of mystery, as the identity of the perpetrator and their motive remain elusive.

This haunting incident becomes an indelible part of Zhang's father's memory, influencing his writing, yet it is a story he cannot publish due to its politically sensitive nature. Growing up, Zhang herself becomes increasingly fascinated by the complex relationship between the victim and the perpetrator, entangled in the horror of this crime. These lingering questions form the basis of Cocoon, an experimental narrative that seeks to uncover possible answers.

At the core of the novel lies the intergenerational impact of historical events, with a particular focus on the enduring consequences of the Cultural Revolution on contemporary Chinese society. Through alternating monologues by the main characters, Li Jiaqi and Cheng Gong, Zhang masterfully excavates family memories and reflects on the struggle to break free from constraints while yearning for a sense of belonging. The paradoxical nature of clinging to delusional family glory adds depth to the narrative, leaving readers to ponder the next steps for younger generations. Cocoon provides detailed depictions of the consequences on parent-child relationships, family dynamics, and emotional well-being, underscoring the long-term effects of unaddressed historical trauma. Zhang skillfully explores the importance of proper reconciliation and understanding to heal the wounds inflicted by the past.

Personally, my bilingual reading experience of Cocoon has deeply resonated with me, prompting me to position myself within the inherited historical trauma. Reading the Chinese version first and then the English translation, I felt a stronger emotional connection to the original text, partly due to my native language and my personal experiences intertwined with the depicted scenes. The Chinese version evoked a sensory experience, evoking vivid memories and a sense of being an integral part of the ongoing impact of the Cultural Revolution. While the English translation is equally brilliant, I did not feel the same level of attachment, raising questions about the unique historical and social context and what Walter Benjamin terms as the "aura" that the original Chinese text possesses, which is challenging to replicate in translation.

Through the opportunity to engage with Zhang herself during the residential weekend, I was able to share in the emotional turbulence of the novel. I wholeheartedly recommend Cocoon to anyone seeking to rediscover clues and answers about the present by delving into the past. It is a captivating and thought-provoking work that invites readers to reflect on the complexities of history and its ongoing reverberations in our lives.

Reviewed by Mia Chen Ma

Reviewed by Trina Garnett, 18/6/23

The premise of Cocoon is deceptively simple: a conversation that takes place during one snowy night between two people who were once childhood friends. By the end of the night, they will have solved a crime that has plagued both their families for decades... but this doesn’t necessarily bring resolution. There are no simple answers here.

The premise of Cocoon is deceptively simple: a conversation that takes place during one snowy night between two people who were once childhood friends. By the end of the night, they will have solved a crime that has plagued both their families for decades... but this doesn’t necessarily bring resolution. There are no simple answers here.

The backdrop to Cocoon is China's Cultural Revolution and its unspoken legacy. Like the author, the two main characters, Li Jiaqi and Cheng Gong, weren’t born at the time of the Revolution, yet they are still affected by secrets kept by those closest to them from that period. The characters might be cocooned from the events, but they aren’t protected from them.

Li Jiaqi has returned to her hometown of Jinan, the capital of Shandong province, to look after her dying grandfather – a renowned doctor and the subject of a documentary. Her childhood friend Cheng Gong is simultaneously preparing to leave Jinan and the home he shares with his Auntie, against her wishes.

Their “conversation” plays out over alternating chapters, switching points of view as they take turns to reminisce and talk about their lives since they last met. The effect is of two interwoven monologues. Although it’s skilfully done, it can be confusing to separate both points of view, perhaps deliberately so. Both characters address each other as “you”; both talk about their “Dad” - although these are two different people - and their grandparents are referred to as Grandad and Grandpa; Grandma and Granny. The distinction between the character names is so subtle it suggests they could be interchangeable. This is not a story of goodies and baddies. Everyone is fallible, even cruel, in their own ways.

Jiaqi’s character is the more interesting of the two narrators and the more relatable. She is also incredibly self-destructive. As Jiaqi’s boyfriend says, "You always see the darker side of life". The story is fabulously dark in places, almost gothic. The settings are bleak to the point of horror – an abandoned water tower, known as Dead Man’s Tower; a once grand mansion now trashed by partygoers; the hospital room where a man lies hovering between life and death for year after year.

It is Cheng Gong’s Granddad who is in a coma in hospital room 317, a victim of the Cultural Revolution. He was left for dead after a “Struggle Session” in which he was tortured, and a nail was driven into his head. Astonishingly his injury is based on a true story. Author Zhang Yueran has spun this macabre detail into a work of fiction. It’s a story that rings truer than if she’d given us a straightforward retelling of events.

Granddad is an artful metaphor for the whole book – a constant reminder that the effects of the Cultural Revolution are ever-present, even when ignored or hushed up. His hospital room becomes the macabre backdrop for all kinds of family occasions and inappropriate activities.

This is a nuanced story about a complicated and traumatic period of history, yet still accessible.

This novel is impossible to categorise, which is one of the reasons I enjoyed it. It’s part crime mystery and family saga, literary fiction and history lesson, and a psychological study of inter-generational trauma. It also feels like a coming-of-age novel, even though both main characters are adults.

Jiaqi and Gong’s conversation is circular - they repeatedly return to past events, revealing more, or different, memories each time as they peel back the layers. They are stuck in the past and it’s left to the reader to decide whether their conversation has helped either of them move on.

Zhang’s language, elegantly translated into English by Jeremy Tiang, is lyrical and even hypnotic. The story is reflective and thought-provoking and one that will stay with you long after you’ve finished reading.

Reviewed by Trina Garnett

Reviewed by Helen Lewis, 13/6/23

Children always know more than you think…

Children always know more than you think…

It is a familiar strategy for parents to seek to shield their children from the adult world, wrapping them up in cotton wool. However, one way or another, the truth will out.

This blistering novel by Zhang Yueran explores the past through the eyes of childhood friends Cheng Gong and Jiaqi. Reunited on a cold winter’s night, they take turns to give their perspective on their shared heritage, the outfall from a cold-blooded murder committed before they were born during the chaos of the Cultural Revolution. As the cocoon of secrecy unravels, layer after layer of trauma is exposed and the secret of Dead Man’s Tower reverberates down through the generations. Try as they might, the adults in the story are powerless to prevent their children from experiencing the impact of their failures. As the saying goes, ‘those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it’.

The Chinese one child policy established during the 1970s is often brushed off by the Western media as resulting in a generation of ‘little emperors’, spoilt children whose every whim is indulged by their affluent parents. A very different picture is painted by Zhang in this novel however – family break-up, isolation, dislocation, absent parents and both physical and emotional poverty. Against a backdrop of grey city streets with snowy pavements, Zhang skilfully peels back the sticking plaster to show a tormented generation, haunted by violence and self-destruction. Like the formaldehyde seeping from Dead Man’s Tower, or Grandad lying in a vegetative state in Room 317, the past refuses to lie down and go to sleep

The gothic atmosphere conjured by Zhang is ideal reading for a cold winter’s night, full of doomed love affairs, spooky buildings and claustrophobic households reminiscent of Bronte’s Wuthering Heights, although here the narrators Cheng Gong and Jiaqi perform a delicate dance, part memoir, part detective work, straining towards the truth but never quite unveiling the whole of the mystery. Cheng Gong is haunted by his ancestors, burning like a cold flame, inciting him to take revenge, whilst his wronged grandfather lies in a hospital bed, a ‘living-dead’ person, suspended between two worlds. And yet he is also a blank canvas for others upon which to project their own realities – zombie, baby, ‘withered orchid’, bread winner, science project, TV biopic and ultimately secret object of devotion. Meanwhile Jiaqi chases the ghost of her own father, absent for much of her childhood, through her romantic encounters with his former pupils and colleagues, striving for connection but unable to find answers to all of her questions.

Zhang’s writing also calls to mind some of the themes of Eileen Chang, who skilfully evoked the class divisions of 20th century Shanghai and Hong Kong by exploring marriages and love affairs across the divide. In Cocoon, the two key narrators are from different sides of the tracks, wilfully ignoring schoolyard prejudices, exploring the forbidden areas of their local area and rejecting the pristine values of Jiaqi’s model-student cousin, Peixuan. Jiaqi’s father marries his sweetheart from his years in the ‘down to the countryside’ movement, who then suffers the consequences of being the ‘bumpkin’, an outsider in a very academic family. He then falls for another impossible bride, the daughter of a man implicated in Grandad’s murder, defending her from local bullies but then becoming trapped with her in caring for her mother, another ‘locked in’ victim of the Cultural Revolution.

Cocoon is certainly not classic detective fiction, but would definitely appeal to those who enjoy Scandi noir. It is quintessentially Chinese whilst at the same time eloquently exploring themes which are relatable across international boundaries. A haunting elegy for a bewildered generation.

Reviewed by Helen Lewis

Reviewed by Michelle Deeter, 2/6/23

While Cocoon is an intriguing book, it is also a depressing read. It can be a little slow and readers need to pay attention to be able to fit all the pieces together. But as long as readers know that the book zeroes in on character development at the expense of a pacey plot, they can still enjoy the book overall.

While Cocoon is an intriguing book, it is also a depressing read. It can be a little slow and readers need to pay attention to be able to fit all the pieces together. But as long as readers know that the book zeroes in on character development at the expense of a pacey plot, they can still enjoy the book overall.

The book is set in a provincial capital in the north of China where life is harsh. It follows the Li family and the Cheng family, and shifts back and forth between the grandfather generation (of the 1950s and 1960s) and the younger generation of the 1980s. Self-destructive Li Jiaqi comes back to her hometown as a result of her mother’s persistent nagging. Ostensibly she returns to take care of her grandfather, but instead of considering his needs, she tests how long he can go without soiling himself. It seems that Southern Courtyard, the grand house, is just another place where she can crash while she figures out her next move. She meets Cheng Gong, her school friend, and they have a long conversation at Southern Courtyard, where Jiaqi’s grandfather is dying. They wallow in their memories, and as Jiaqi says, “my memory would rather cling to the suffering” so much of the focus is on the violent and abusive family members who raised them and their parents. Rather than hiding their misdeeds, Jiaqi and Cheng Gong are frank about the bad decisions they made in their lives.

Jiaqi has a mean streak and says incredibly hurtful things to the people who are close to her, including her own mother and Cheng Gong, who is supposed to be her best friend. Cheng Gong was bullied as a child and had every intention of leaving the town but then somehow ends up stuck there for decades. He can be unkind, but compared to his violent father he is rather placid. Both Li Jiaqi and Cheng Gong admit that they would not be friends if it weren’t for the funny set of circumstances that brought them together.

Even though the book covers memories that are nothing like my own childhood, I am able to relate to the main characters. I guess we all know someone like Peixuan, who is so perfect at everything that we wish she would make a mistake every once in a while. We all know someone like Cheng Gong’s auntie, who should have the small town left years ago but stayed around until her life became mundane and disappointing. Jiaqi will do anything to get her father to love her, and I think I understand that sentiment. The memories that relate to the Cultural Revolution are gruelling, and it turns out there is a deep, hidden reason why so many people told young Cheng Gong not to hang around Jiaqi. Again, these memories do not relate to my personal experience, but they provide a motivation for various family members to act the way that they do.

The translation is excellent. Certain turns of phrase, such as “soberness is a barrier that exists to be smashed,” make me jump with joy. The dialogue is believable, helping to shape the character’s personalities. Cheng Gong’s granny says some appalling things to Cheng Gong when he first arrives in their house, but because everything she says is appalling, it becomes totally believable.

In short, don’t read this book because you want to learn more about Chinese history. The historical aspects are not showcased in this book, they merely serve as a quiet backdrop. Instead, read this book because you want to read something intense and somewhat grim but ultimately worth your trouble. The character development is excellent and the way the people seem to take pleasure in remembering sad times and tormenting each other is ultimately compelling.

Reviewed by Michelle Deeter

Reviewed by Angus Stewart, 24/5/23

I’ve read quite a lot of translated Chinese fiction that you might call “literary” – that is, realist rather than speculative (but not afraid, in some cases, of a dash of magical realism), more open to a free play of cause and effect than constrained by genre conventions (on balance, at least), and perceived as being more ‘worthy’ of accolades (and subsidy, perhaps) than popular works.

I’ve read quite a lot of translated Chinese fiction that you might call “literary” – that is, realist rather than speculative (but not afraid, in some cases, of a dash of magical realism), more open to a free play of cause and effect than constrained by genre conventions (on balance, at least), and perceived as being more ‘worthy’ of accolades (and subsidy, perhaps) than popular works.

A lot of that fiction deals with one or several of the various traumatic and transformative stages of Chinese history. Colonisation might be in there, and so might the civil or anti-Japanese wars. The Cultural Revolution may also feature, and this stands out, because in Chinese fiction the Cultural Revolution is the only real political failure of Mao Zedong’s premiership that (certain) authors can depict (in certain ways) without getting blacklisted.

Zhang Yueran’s Cocoon is literary and it does deal with the Cultural Revolution, but in a way that my readings haven’t shown me before. This author is younger than the other big names famous for scrawling upon the scars of ’66-’77. Zhang Yueran is decidedly not, let’s say, Jia Pingwa. She was born in the 80s, and that’s why the zone in which she dramatises this topic is the aftermath. Cocoon is a dual bildungsroman (weighty words for a weighty work) about two children who slowly transform into adults amid the fog and shadow cast over their families by one terrible incident that was engendered and permitted by the lawless and vindictive decade that preceded their entry into the world.

While working my way through the layers of Cocoon, I wasn’t always thinking about the Cultural Revolution. Far from it. The story depicts many other mesmerising and painful things: slices of life from northern China in the reform era, shades of mental illness (though never named as such) pushing characters to alcohol and adultery, delusion and dishonesty, doomed love, directionless love, denied love, dependence, suspicion, reconciliation, mystery… but, as the author herself has emphasised, it all ties back to an unnameable trauma that was inflicted at length, endured, and then pushed under the rug. Even though authors like Jia and Zhang are willing (and able, for now) to write in some fashion about the cultural revolution, society at large isn’t – and the government presiding over that society is in no rush to facilitate the conversation.

I am breaking my own rules here – I prefer not to let red or anti-red politics (or even national questions and allegories) dominate my dialogues (monologues in this case) about Chinese lit. So let it be known that in Cocoon we have a serious artwork that is moody and mournful and sensitive to just how easily our fears and longings and hatreds can leave us resigned to dying alone, buried under snow. We have, it might be argued, a novel built around a mystery – but nobody hired the detective in time, and in any case, nobody’s paying. In a better world, the dueling narrators of Cocoon, beautiful Li Jiaqi and solemn Cheng Gong, would have become star-crossed lovers, with reason, justice, and history’s healing hand on their side. Good luck finding that better world.

Reviewed by Angus Stewart

Reviewed by Zahra Raja, 22/5/23

Cocoon is the story of two friends, Li Jiaqi and Cheng Gong, who after 18 years apart reunite to unpick the traumas of their past. Through the course of the novel and their alternating narratives, we learn about how a crime committed during the Cultural Revolution ties them inextricably together and leaves an indelible impression on them, despite being of the generation directly afterwards. The author Zhang Yueran is also of this generation, and I was fortunate enough to be able to hear her speak on how her own experiences had bled into the book; given that the PRC is unlikely to ever allow this topic to be freely discussed, the resulting wounds will remain open and continue to fester for decades to come.

Cocoon is the story of two friends, Li Jiaqi and Cheng Gong, who after 18 years apart reunite to unpick the traumas of their past. Through the course of the novel and their alternating narratives, we learn about how a crime committed during the Cultural Revolution ties them inextricably together and leaves an indelible impression on them, despite being of the generation directly afterwards. The author Zhang Yueran is also of this generation, and I was fortunate enough to be able to hear her speak on how her own experiences had bled into the book; given that the PRC is unlikely to ever allow this topic to be freely discussed, the resulting wounds will remain open and continue to fester for decades to come.

The crime in question relates to Cheng Gong’s grandad, who during the Cultural Revolution, had a nail driven through his skull and into his brain, which was not treated quickly enough and led to his comatose state. He never awakens, and thus symbolises the aftermath of the Cultural Revolution; he is simultaneously a channel for inter-generational guilt, a mystery to be solved and a ghost that can never be laid to rest.

While the crime is a key plot point, the focus of the book is more centred around the resulting trauma on Cheng Gong and Jiaqi. Jiaqi notes that “growing up felt like making it through the fog and seeing the world clearly…we’d just wrapped that fog around ourselves, each of us spinning it into a cocoon”, which is a fair summary of the attitudes of the two protagonists. Jiaqi in particular wears her trauma like a bulletproof shield, and in so wearing it becomes impervious to any criticism or any inclination of moving on from it. Her actions and views can be viewed as a direct rejection of the Cultural Revolution; she idolises her father, an intellectual (who were denounced during that period) and reviles her mother, an illiterate woman from the countryside (who were lauded as role models). This is in spite of her mother and new stepfather treating her well and her father being irresponsible and absent. She is a frustrating character whose obsession with the past brings about the crumbling of her present; to the extent that she tracks down and sleeps with multiple of her father’s former colleagues in order to feel closer to him, bringing about the end of her engagement to probably the only sane person in the novel.

Cocoon is a fascinating exploration into the aftermath of one of the most catastrophic campaigns in the late 20th century, particularly its far-reaching impact on subsequent generations. Can the ghosts of our pasts ever be laid to rest if a society is not permitted to seek justice and closure? Zhang does not seem to think so, and mentioned during the roundtable discussion that China will not ever be able to lay these ghosts to rest due to state suppression and censorship.

A final note on the masterful translation by Jeremy Tiang – I always enjoy his translations and Cocoon was no different. One thing to point out is that you need to pay attention to keep all the family members straight; in Chinese there are different names for your maternal and paternal sides of the family vs the same names in English which can get confusing but this was made easier by the particularly helpful usage of “Grandpa” vs “Grandad”, “Granny” vs “Grandma”, the more colloquial forms reserved for Cheng Gong’s lower class family and the formal forms for Jiaqi’s elitist grandparents. Overall a great read and thoroughly recommended.

Reviewed by Zahra Raja