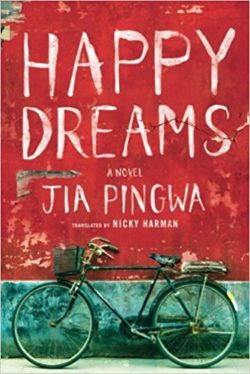

Happy Dreams by Jia Pingwa

translated by Nicky Harman

Amazon Crossing, 2017

Publisher's Blurb

From one of China’s foremost authors, Jia Pingwa’s Happy Dreams is a powerful depiction of life in industrializing contemporary China, in all its humor and pathos, as seen through the eyes of Happy Liu, a charming and clever rural laborer who leaves his home for the gritty, harsh streets of Xi’an in search of better life.

After a disastrous end to a relationship, Hawa “Happy” Liu embarks on a quest to find the recipient of his donated kidney and a life that lives up to his self-given moniker. Traveling from his rural home in Freshwind to the city of Xi’an, Happy brings only an eternally positive attitude, his devoted best friend Wufu, and a pair of high-heeled women’s shoes he hopes to fill with the love of his life.

In Xi’an, Happy and Wufu find jobs as trash pickers sorting through the city’s filth, but Happy refuses to be deterred by inauspicious beginnings. In his eyes, dusty birds become phoenixes, the streets become rivers, and life is what you make of it. When he meets the beautiful Yichun, he imagines she is the one to fill the shoes and his Cinderella-esque dream. But when the harsh city conditions and the crush of societal inequalities take the life of his friend and shake Happy to his soul, he’ll need more than just his unrelenting optimism to hold on to the belief that something better is possible.

Reading Chinese Network Reviews

Reviewed by Cuilin Sang, 19/2/18

In early January of 2005, an investigative news article in Southern Weekly, and a news story on Hongkong-based Phoenix TV captured Chinese audiences’ attention: several migrant workers from Hunan province in central China attempted to board a train without tickets, and, astoundingly, with the corpse of a middle-aged man. The corpse was covered in a quilt, apparently by someone trying to pass it off as a typically clumsy piece of luggage that so many migrant peasant workers would carry on a train. The motive, as revealed later after police questioning, was to bring the body back home for burial. In the village where they came from, to be buried under ground after death was still considered the only proper way to rest in peace permanently. In Chinese it is called rutuwei’an (入土为安 ), literally translated as “to be settled is to be under ground,” a rare luxury almost impossible for a city folk in contemporary China to be allowed to have. And perhaps the most valuable luxury a city folk would be jealous of a “country bumpkin” for.

In early January of 2005, an investigative news article in Southern Weekly, and a news story on Hongkong-based Phoenix TV captured Chinese audiences’ attention: several migrant workers from Hunan province in central China attempted to board a train without tickets, and, astoundingly, with the corpse of a middle-aged man. The corpse was covered in a quilt, apparently by someone trying to pass it off as a typically clumsy piece of luggage that so many migrant peasant workers would carry on a train. The motive, as revealed later after police questioning, was to bring the body back home for burial. In the village where they came from, to be buried under ground after death was still considered the only proper way to rest in peace permanently. In Chinese it is called rutuwei’an (入土为安 ), literally translated as “to be settled is to be under ground,” a rare luxury almost impossible for a city folk in contemporary China to be allowed to have. And perhaps the most valuable luxury a city folk would be jealous of a “country bumpkin” for.

Jia Pingwa’s novel Happy Dreams is partly inspired by this true story, which also inspired a blockbuster movie starring one of the nation’s most popular comedians, Zhao Benshan. The man in the true story, Li Shaowei, who became known to the nation for trying to carry the corpse of his fellow countryman back home, reportedly felt conflicted about his traumatic experience being adapted into an oversimplifying if not misleading comedy confirmative of the mainstream values. Happy Liu, the protagonist in Happy Dreams, on the other hand, is definitely not an oversimplifying version of Li Shaowei. If anything, he might be too complicated. Happy, the first-person narrator in this novel that in many ways could be read as an adult bildungsroman, is a nexus where decades of Jia’s observation and contemplation of peasants and his deep compassion towards them are convoluted. As Jia explains in the afterward, Happy Liu, the self-appointed “city dweller” who voluntarily changed his name from a rather sophisticated, gentlemanly name Shuzhen 书祯 to Gaoxing 高 兴, or Happy, is an old acquaintance of his and has made appearances in his previous novel Qinqiang, or Qin Melody. The tragic experience of the actual corpse-carrier, Li Shaowei, the experiences of Happy Liu, the trash picker that Jia Pingwa knows in real life, and the insecure, unsheltered life of other trash pickers that Jia interviewed in Xi’an, all contribute to the formation of the Happy Liu in Happy Dreams.

Happy, as his name suggests, is a character that is almost hopelessly optimistic. Based on the author’s impression of the real Happy Liu, that is, “a lotus growing out of pond mud,” or “a clean life in a filthy place,” the Happy in the novel is potently capable of creating heterotopias, or the dwelling places for his happiness. His heterotopias are not as overtly fantastical and supernatural as those in the work of the British author China Miéville. Their fantastical and supernatural qualities are implied, even insinuated, under the monolithic surface of the hard-core realism, the most popular and effective literary -ism for the Chinese authors who wish to be the voices of the most pressing social issues. Happy’s heterotopias, embodied in the pagoda, the Chain-Bones Bodhisattva, and even the cat, can feel a bit out of place, at odds with the keynote of realism. In this “city” story, the fantastical, magical and alchemical elements that once worked concertedly and effectively in Jia’s previous work centering on the village life in his hometown Shangluo, such as Qinqiang, have been mostly crowded out, just like the migrant peasant workers picking trash in the city being crowded out of the life they dream to live. The significance and grandeur Happy attempts to attach to the Buddhist objects and images in terms of Yichun, the woman he loves, is too much, disproportional even taking into account the horrid injustice she endures. And the omen the cat bears in terms of his relationship with Yichun seems unduly unrecognized. The heterotopias into which he migrates his happiness are constructed out of his over- and under-interpretation of reality. The discrepancy between his heterotopias and reality is so despairingly gaping that his unrelenting optimism seems to border on delusional thinking, which, as a matter of fact, reflects how trodden and battered his psyche is.

The persistent first-person narration allows Jia to adopt a vivid, occasionally dialectal yet highly literary language. But Jia, who won the first “The Dream of the Red Chamber Award,” has always had an acute sense of the rhythm and the infectiousness of the language. His meticulous attention to detail usually empowers the text with the strength and allure of the more primitively sensual, agrarian life. In Happy Dreams, this attention continues with a deep compassion embedded in the first-person narrator towards the peasants living in the disorientation of a fast-changing, urbanized society. Nicky Harman’s adept translation shows an intimate knowledge of the style and use of language in Jia’s work. Her deft choice of words and tone and her equally meticulous attention to detail not only bridge the semantic, but also the contextual gaps between the two languages.

Reviewed by Cuilin Sang

Reviewed by Tamara McCombe, 12/2/18

For over twenty years Jia Pingwa has been a literary luminary in his native China, but as yet remains relatively unknown in the West, astounding. Happy Dreams is the fourth of Jia’s novels to be translated into English, but like the other translations of his work, a gap of ten years stands between the Chinese and English versions.

For over twenty years Jia Pingwa has been a literary luminary in his native China, but as yet remains relatively unknown in the West, astounding. Happy Dreams is the fourth of Jia’s novels to be translated into English, but like the other translations of his work, a gap of ten years stands between the Chinese and English versions.

Jia’s style draws heavy inspiration from the vernacular novels of the Ming and Qing dynasties (1368–1911 AD) but its historical links are easily lost within the modern realism of his work. In Happy Dreams, Happy Liu and his country bumpkin friend Wufu are trying to make their way in Xi’an as rubbish collectors rather than earning pittance toiling the lands in the countryside. Happy is just like the youthful author stranded in the countryside who during the Cultural Revolution wrote to a friend saying "Every time I see one of our friends going out into the world, I'm jealous. I have a longing to leave. I'm not going to accept fate and go work as a farmer. I know that I have to make something of myself." Happy will not accept the lot of remaining a peasant.

The author grew up in a peasant family in Shaanxi, where all his novels are set and where the protagonists are from. Like the lead in Happy Dreams, Jia moved to Xi’an to find his literal and cultural fortune. Xi’an during the Tang dynasty (c.7th century) was the political and spiritual centre of the Chinese empire, also possibly the largest and most cosmopolitan city in the world. However, in Happy Dreams and Jia’s earlier work Ruined City, Xi’an’s dilapidated and literal dirty side is described in vivid detail. It is Jia’s appreciation of the minutiae within larger themes that characterises his writing style. The vulgar slurping noises of the trash pickers as they consumer their noodles and the explanation of dust on the window sill drifts Jia away from the drama and scandals of the plot. At first these digressions are charming windows into the fictionalised lives of the migrant workers, but gradually leaves the reader with the urge to skip pages to get on with the story. In this sense Happy Dreams is like other classics of Chinese literature — The Water Margin, Journey to the West, The Dream of the Red Chamber, The Scholars – in that it is composed of episodic stories wandering along indifferent to plot progression, yet also makes the story two hundred pages longer than needs be.

Chinese tradition places great significance on names and Happy Dreams is no exception. Wufu for instance can be translated as ‘five riches’ or ‘no riches’ depending on the tones used by the speaker – an ominous hint to what lies in store for this character. The rubbish collectors also roam streets with names such as ‘Prosper Street’ for discarded items which they can turn in for cash. Jia's given name, Píngwá 平娃, literally means 'ordinary child', a name suggested to his parents by a fortune teller following the death of their first born child. He later chose the pen name Píngwā 平凹, a play on his given name. The character 平can mean 'ordinary' or 'flat'; in southern Shaanxi dialect the character 凹for 'concave', and by extension 'uneven', is pronounced wā, similar to wá or 'child' in his given name. The characters for flat and uneven next to each other also imbues the name and consequently the author with the characterisation of evenness or balance. Protagonist Hawa Liu, like the author, adopts a more artistic name, that of ‘Happy Liu’.

Despite the grim living conditions and fates of the rubbish collectors and prostitutes in the novel, Happy Dreams is a novel championing the optimism of those people essential to modern Chinese society and yet who are often looked down on and their appreciation of life’s small pleasures. As Happy muses: “Too bad there wasn’t a [street named] Trash Pickers Lane. Thirteen dynasties had made Xi’an their capital, and each dynasty must have had countless trash pickers, but there was no street that bore their name.”

Happy Dreams is a well-crafted book, seamlessly splicing the portrayal of a section of

contemporary Chinese society with a nostalgic devotion to Chinese literary technique, the

former threatening the latter. Which is why it was inciting to read the author’s afterword

explaining the book’s meanings, its origins and writing progress. If an author has truly done

their job in conveying messages via characterisation, literary technique and plot then no post

script is needed. The translation by Nicky Harman is in American-English in that she uses spellings such as ‘color’ rather than ‘colour’. She does an excellent job of familiarising the

Western reader to the characters by translating their crude language into equivalent Western swear words rather than literally translating the Chinese, yet also keeps the foreignness of the setting by using the pinyin for certain commodities such as foods. I enjoyed Happy Dreams

for its subtleness in style and lack of the bitter scapegoatism so often used by

contemporaneous authors such Xu Xiaobin in Crystal Wedding. The novel was unnecessarily long but this does not distract from the fact that it is a quality read.

Reviewed by Tamara McCombe

Reviewed by Paul Gardner, 17/1/18

Happy Dreams tells the story of two migrants who leave the village of Freshwind to work in Xi’an, one of China’s largest cities. The story is narrated from the viewpoint of Happy, who changes his name from Hawa Liu, to reflect his optimism about the future, when he arrives in the city with his friend Wufu.

Happy Dreams tells the story of two migrants who leave the village of Freshwind to work in Xi’an, one of China’s largest cities. The story is narrated from the viewpoint of Happy, who changes his name from Hawa Liu, to reflect his optimism about the future, when he arrives in the city with his friend Wufu.

Happy is determined to become a true city man, but Wufu yearns for his life back in Freshwind. Happy tries to help Wufu navigate life in the city and to educate his friend out of his peasant ways, telling him that when he eats there should be ‘no squatting on the bench, no smacking your lips, no shouting about how good it is, no swilling tea around your mouth’.

The pair are part of the ‘single biggest migration in China’s history’. As Happy observes, ‘Country folk flock to the city to earn money doing jobs that city folk don’t want to do anymore, the dirty, heavy work’. Around one in three people of working age in China (about 300 million people) are rural migrants who have moved into fast growing, and increasingly prosperous, cities. http://www.clb.org.hk/content/migrant-workers-and-their-children

Together, Happy and Wufu get jobs as trash pickers. Private trash pickers play an essential role in Chinese cities, similar to the rag and bone men, like my own grandfather, who were a common feature of British cities until local councils developed waste collection services in the second half of the twentieth century. Happy and Wufu supplement their income by taking on a number of other roles, including shifting sacks of cement, selling coal and illegal medical waste. When the pair take on their last job, digging a ditch, it turns out that Wufu is in effect digging his own grave. After days of back breaking work, Wufu collapses, and with no money for hospital fees, he dies in a hospital corridor.

Like Yu Hua’s To Live, this book is, in part, about the resilience of the human spirit. Happy, Wufu and their neighbours keep going despite everything life throws at them. After heavy rains, Happy sees some green shoots emerging from the mud at the side of their alley. ‘What a will to live those shoots had’ he thinks, ‘and they were only a lowly form of life!’ For the most part, Happy retains this optimistic outlook throughout the book, despite the many setbacks he endures trying to scrape a living at the bottom of Xi’an’s social pile.

Above all, the book is an attempt to humanise China’s migrant workers. Jia, who came from a poor rural village himself, reflects that if he had not been fortunate enough to gain a place in college, he could easily have found himself working as a trash picker. ‘It grieved me to think of the poverty, low status, loneliness, and discrimination they experienced, having left the land to come to the city’. Happy observes that while out trash picking he is largely ignored by the city’s residents. ‘If I smiled and greeted them, they would walk past as if I weren’t there. As if I were a leaf or a scrap of paper blowing down the street.’

Worse still, the migrants are often treated as being less than human. After Wufu dies, Happy attempts to carry his friend’s body out of Xi’an, just as both men spend much of the book carrying away other people’s rubbish. And that is just how many of those who lived in the city saw them, as simply part of the trash. One of Happy’s neighbours sees another migrant threatening to commit suicide by jumping from a building, a tactic sometimes used to compel employers into paying unpaid wages. However, bystanders goad the man into jumping. Happy’s neighbour observes with despair, ‘He was a migrant worker, and to city folk, it was like watching a performing monkey.’

I started reading this book at the end of 2017, just after the authorities in Beijing started clearing neighbourhoods occupied by poor migrant workers. The residents, who were described by city officials as the ‘low-end population’, were given little or no notice, and no alternative accommodation, despite the freezing weather. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/nov/27/china-ruthless-campaign-evict-beijings-migrant-workers-condemned

Happy tells Wufu that they should not allow themselves to be treated as somehow inferior to the people who lived in the city. In fact, in the book, it is these ‘low end’ people who exhibit humanity and strength of character, while the city folk are often unprincipled and uncaring. Employers cheat migrant workers out of their hard earned cash and city officials are corrupt. The government spends millions beautifying gardens, while neglecting the poor. Prosperous city residents eat themselves sick, while a few streets away migrants battle hunger.

Meanwhile, the community of trash pickers strive hard to make a better life for themselves and look out for each other. Happy attempts to take Wufu’s body back to their village to be buried, rather than being cremated in Xi’an and turning into an ‘unquiet ghost’. ‘Whether he was dead or alive, I couldn’t let him down. That was my belief; that was the rule in Freshwind.’

Jia succeeds in turning the reader’s gaze away from the bright lights of the city, towards the people who provide so many of the city’s essential services. He says that after completing his research for the book, ‘deep in my heart, I loathed and resented the city, resented it on behalf of those trash pickers’. After reading this book, it is difficult not to share that feeling of resentment. However, this is by no means a book of unrelenting misery. Aided by Nicky Harman’s excellent translation, Jia succeeds in his aim of making the story ‘real, and detailed, so that it felt warm and intimate’. For a brief period, we become part of the lives of the trash pickers, and through Happy, Jia succeeds in telling us about their lives with humour and compassion.

Reviewed by Paul Gardner

Reviewed by Cat Hanson, 8/1/18

Happy Liu wants to find his space in China. At the head of the millennium, China is changing. Xi’an has a shiny, newly-constructed Hibiscus Park at 50 yuan per ticket. Red Guard blood-pacts are now faded scars, and Happy Liu has moved from the rural village of Freshwind to one of China’s largest cities.

Happy Liu wants to find his space in China. At the head of the millennium, China is changing. Xi’an has a shiny, newly-constructed Hibiscus Park at 50 yuan per ticket. Red Guard blood-pacts are now faded scars, and Happy Liu has moved from the rural village of Freshwind to one of China’s largest cities.

Accompanied by Wufu, a fellow Freshwind villager, Happy sets off to Xi’an in order to delve into the world of trash-picking - a system of collecting rubbish to later sell to plants or buyers. The ‘trash-pickers’ form a piece of the jigsaw of modern Xi’an - a lattice of characters from landlords to traffic officers. Even Lively Shi makes an appearance in several roles, including beggar and musician.

With an expensive packet of cigarettes and a leather wallet in hand, Happy accepts his new position as a Trash Picker, but not without keeping one eye on what it is to be a ‘city man’. From the beginning, Hawa, who later becomes ‘Happy’, is convinced of a role that must be played to truly fit in in Xi’an, starting firstly with nominative determination. He scolds the rough-around-the-edges Wufu for his loud restaurant antics. A ‘city man’ doesn’t dress like that. A ‘city man’ doesn’t eat like that. Really, as is revealed throughout the story’s dialogue-heavy chapters, there is no ‘city man’ at all - only the vast array of characters that create any city.

The true fate of Wufu, Happy’s right-hand man, is imparted from the book’s opening pages. Despite Happy’s lecturing, we recognise the strong bond between the two. Happy may be on course to find a wife to fill his freshly-polished pair of high heeled shoes, but Wufu is a part of his history and home that he can’t quite shake off.

Nicky Harman’s translation really captures the witty and rapid dialogue. The familiarity between characters sings through the staccato and quick-fire lines - just as the language would be if it fell on comprehending ears. Language-based puns are also smoothly adapted without the need for footnotes - for example, the joke of the character ‘Gules’ becoming ‘Goolies’. Throughout, the translation never warps the storyline or detracts from the rich descriptions of the environment originally written by Jia Pingwa.

In the end, Happy has experienced the twists and turns of city life. Sometimes, his inner instructions to live life as a ‘city man’ pay off. Other times, the city gets the better of him. But with the final fate of Wufu, who was originally so ‘unsuited’ for Xi’an in the eyes of others, it is only he who stays behind, living on forever inside the walls of the city.

Reviewed by Cat Hanson

Reviewed by Joy Qiao, 7/1/18

The 23rd August 2017 witnessed the simultaneous release of Happy Dreams on 14 websites of Amazon worldwide, which enabled readers in 183 countries to get the book as quickly and easily as possible. Also, the book is the only Chinese literary work included in Kindle “First” Project in 2017. Why this day? And Why this book?

The 23rd August 2017 witnessed the simultaneous release of Happy Dreams on 14 websites of Amazon worldwide, which enabled readers in 183 countries to get the book as quickly and easily as possible. Also, the book is the only Chinese literary work included in Kindle “First” Project in 2017. Why this day? And Why this book?

The day was chosen for being the opening day of the 24th Beijing International Book Fair, the world’s second largest book fair, which is a great chance for “going out” of Chinese Culture and literary fiction. Then why this book? Apart from the fact that it comes from the prominent Chinese writer Jia Pingwa, the content of the book is the main attraction for English readers who want to learn about modern China.

In sixty-two chapters, Happy Dreams explores the rapid industrialization of China in the last twenty to thirty years, following the protagonist Happy Li’s move from the small village Freshwind to the bustling capital Xi’an. This in fact is the general way most peasants move to the cities in China. They hope to live a better life in cities and also hope to provide a city foundation for their children and later generations. They strive to live amid a cruel reality, just like Happy Liu and his buddy Wufu. Their love for life is always there. You may find in between the lines the bitter life of these people, or the heartwarming loyalty between friends, or even the class or social inequality. No matter what it may be, it’s the most honest portrayal of real life, and can certainly touch people’s hearts and be enlightening. Just as Jia Pingwa the author wrote in the postscript, “So I made Happy Liu the subject of my novel. He was, after all, unique. Yet he was also typical. He had turned into the man that he was now because the more life weighed on him, the more he knew how to bear difficulties lightly; the more he suffered, the more enjoyment he got out of life.”

Of course, we shouldn’t forget the translator Nicky Harman here. It is she who tries her best to make the novel read easily in English. I can imagine all her efforts in turning those dialects, puns, jokes, even swear-words into English and dealing with assorted other difficulties. Just take the names of the protagonist Happy Liu and a minor character Lively Shi as example. These names are in fact great puns used in the novel. “Happy” in Chinese “gaoxing”, and “Lively” in Chinese “renao”, here not just the names of the two persons, they further transfer the deep meaning — the main characteristics of the two persons and their attitudes toward life. So this translating strategy is superior to the general way of transliterating. Another example of translation impressing me most is that of the swearwords. Nicky tried to turn the Chinese ones into their English equivalent, keeping Jia Pingwa’s style to the utmost degree. For example in describing Lively Shi’s cowardice when he saw the policeman, Happy Liu was so angry that he called him a “stupid fucker”. Maybe there’s one last point I’d like to say—“the lost” in translation. For all the differences in cultures and languages, there must be something lost. In this novel, the flavour of some dialects is not and in fact cannot be fully transferred. What I want to say here is that maybe we should focus more on what we gain rather than what we lose since losing is unavoidable in translation.

Reviewed by Joy Qiao

Reviewed by Andreea Chirita, 5/1/18

When two migrant workers, who are journeying to the big city of Xi’an in search of a better life, have names like Happy Liu and Wufu (Five Happiness), you instinctively know that the expectation of a happy narrative are false, and that the novel will conclude in a dark, comedic tragedy.

When two migrant workers, who are journeying to the big city of Xi’an in search of a better life, have names like Happy Liu and Wufu (Five Happiness), you instinctively know that the expectation of a happy narrative are false, and that the novel will conclude in a dark, comedic tragedy.

The author of Happy Dreams, Jia Pingwa, starts the novel with the depiction of Happy Liu carrying the corpse of his friend to their hometown after an unhappy stint as a trash-picker in the streets of the ancient Chinese capital. Jia elegantly conveys the psychological diversity of his characters - specifically migrant workers- and their unexpected, ingenious, eye-opening ways to understand, cope and adjust to the economic competition that defines contemporary Chinese cities.

For this novel, Jia researched the conditions of migrant workers in Xi’an with anthropological minuteness. The main character and narrator of the story, Happy Liu, has a beautiful mind capable of grasping both his own and his companions’ struggles with love and with survival within the alienating borders of the metropolis. In contrast, Wufu’s rudimentary inner world, which is blunt, unpolished and naïve, serves as a charming counter weight. Wufu is another version of Pigsy from Journey to the West, utterly oblivious of his charming rawness, but in Jia’s novel, he is depicted as a garbage collector who struggles to make ends meet to support his impoverished left-behind wife and three children. A cast of other characters--prostitutes, beggars and construction workers -- populate the novel and collectively voice the crass inequality of the marginalized and the privileged.

Happy Liu narrates the story in a jovial yet heartbreaking prose while being sympathetic to all the characters consumed by the social drama of survival of the fittest. Whether confronting city people or country people, Happy Liu’s benignant and analytical dissections do not spare anyone. In an encounter with a nouveau-riche lady who becomes suspicious of his good intentions, Happy Liu says, “What a bitch, so rude! Why take out your problems on me? You might be pretty, but there are plenty of prettier women out there. You might be rich, but I’ve been to plenty big businessmen’s villas collecting trash. Would you slam the door like that on me if I wasn’t a trash picker?”

Palpable and lively characters evolve through natural dialogues that are laced with grotesque and nativist humor. For example, provincial slang does not get lost in dialogues, which could deprive characters of authenticity. Instead, translator Nicky Herman wonderfully renders the simplicity of characters’ spoken language, which attests to their believable existence and marginalized social background.

Jia’s jovial dialogue pivots around three main themes: money, food, and ghosts. These themes are often displayed in an outburst of grotesque, humorous dialogue: “Wufu had a face permanently creased with worry, like a pig, but when he was taking a crap, his face wrinkled in a smile. (…). He must have eaten a big lunch because he kept farting. Every time Wufu swore at the driver, he squeezed out a fart.”

For contemporary Chinese writers, using the imagery of humors leaking out of characters’ bodies to highlight the anxiety and threat posed by marginalized groups within the ever-changing society is not a recent narrative strategy. Jia’s ‘fecalopolitics’ writing style humanizes the characters, gives them an earthy aura, showcasing their paradoxical local and universal psychological simplicities. Furthermore, the author’s excessive use of scatological aesthetics builds up the chronotopes of wicked social change within China’s new capitalist order and attest to the country’s conversion of human excrement into money.

Among the novel’s sixty-two chapters, I am hard-pressed to find a single chapter that does not involve a characters’ struggle for money and how the lack of it controls their destiny. Wufu, for instance, following his unexpected sickness, cannot afford the luxurious healthcare to extend his life with “thirty yuan per hour”, which results in his death. After he passes away, Happy Liu hands to Wufu’s wife the money he pretends to have have saved for burial, and in a gesture of absolute normalcy, “she licked her finger and counted the bills one by one, then got her brother to count again.” Whenever money is involved, the narrative is at its cynical peak. In the novel, cash is fictional and seemingly beyond reach. Yet when within the reach, money becomes ‘ghost money’ that is burned for the dead.

Money and its ghostly qualities are destined to fuel the desires of the many ghosts that populate Wufu and Happy Liu’s imagination. By the end of the novel, the reader confronts a striking reality: that despite the urban location of the novel, there is no memorable character from the city. This ghostly presence mimics the city dwellers, whose existences are unperceivable and irrelevant in the novel. Even their ‘right’ to rest into the city after death is displaced by Wufu’s lingering ghost, who, unable to return to his native Westwind for burial, is “destined to stay here too. […] Only Wufu, forever an unquiet ghost, hovering above the city streets.”

Jia’s literary vision is meant, in his words, ‘to make people live a beautiful life,’ and it is invigorating to see how his characters’ simple minds, altered morally to diverse degrees, can inspire into the most pretentious and sophisticated readers exactly that: the urge to live beautifully.

Reviewed by Andreea Chirita