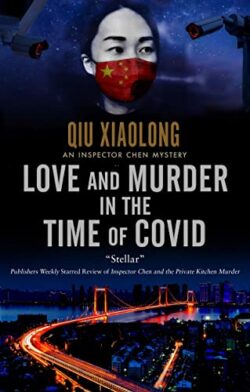

Love and Murder in the Time of Covid, by Qiu Xiaolong

(Severn House, 2023)

Publisher's Blurb

Former chief inspector Chen faces a tricky serial murderer case at the height of the Covid pandemic - and risks everything he has to expose the deadly effects of the Chinese Communist Party's so-called zero Covid policy to the world.

to expose the deadly effects of the Chinese Communist Party's so-called zero Covid policy to the world.

Over two million copies of the Inspector Chen series sold worldwide.

The Covid crisis is at its height in China. Ex-chief inspector Chen Cao is horrified by the way the Chinese Communist Party are using the pandemic as an excuse to put the Chinese people under blanket surveillance and by the soaring number of deaths caused not by Covid, but by the CCP's inhuman 'zero Covid' policy.

Chen is debating whether to translate the 'Wuhan File' - a diary of life during the Wuhan disaster smuggled to him by a close friend - and expose the CCP's secrets to the world when to his surprise he is summoned by a high-level party cadre to help investigate a series of murders near a local Shanghai hospital.

Under pressure from the Party to reach a quick conclusion and help maintain political stability, Chen investigates, aware that he too has been placed under omnipresent, omnipotent surveillance.

And as he works, determined to uncover the truth, no matter what, he risks everything by deciding to translate the Wuhan Files. For one thing is true in China: you must be absolutely loyal to the Party. Otherwise, you are considered absolutely disloyal, and the consequences are dark indeed . . .

Reading Chinese Network Reviews

Reviewed by Mia Chen Ma, 30/6/23

Qiu's Inspector Chen series has always been popular among readers from different cultures. However, his newest novel, Love and Murder in the Time of Covid, is particularly timely and gripping. It is a must-read for anyone seeking to understand how the COVID-19 pandemic has profoundly transformed every aspect of contemporary life.

Qiu's Inspector Chen series has always been popular among readers from different cultures. However, his newest novel, Love and Murder in the Time of Covid, is particularly timely and gripping. It is a must-read for anyone seeking to understand how the COVID-19 pandemic has profoundly transformed every aspect of contemporary life.

During the Leeds residential weekend, Qiu himself revealed that his motivation for writing this novel goes beyond literature or the crime fiction genre. His main objective is to faithfully record an important part of history that should not be forgotten. He emphasizes the significance of comprehending the past and avoiding historical amnesia. Qiu exposes how easily and quickly society tends to forget trauma in its pursuit of normalcy, choosing to bury its own memories. His writing style occasionally adopts the tone of a news report or an analytical piece, further enhancing the documentary-like quality of the story.

The existence of the Wuhan File in the novel, as an authentic record, guides readers to explore the various factors contributing to the disastrous outcomes of the zero-COVID policy. These factors include epidemics, politics, social dynamics, and the distorted ways in which people think and act under immense pressure. Qiu's insightful observations shed light on how these issues are not isolated incidents but rather the result of deep-rooted social and political problems that have developed within the authoritarian system over time.

The concepts of surveillance and self-censorship play a significant role throughout the narrative. Qiu highlights the insidious nature of self-censorship and the mechanisms that lead individuals to withhold sensitive information. He draws parallels between surveillance cameras and the historical bao jia system, illustrating how control has been ingrained in Chinese society for centuries. Qiu's juxtaposition of classical Chinese landscape painting, where blank space speaks in silence, with the notion of self-censorship, creates a compelling metaphor for the hidden constraints individuals face.

However, the portrayal of the female assistant, Jin, raises concerns about gender stereotypes. Depicting Jin as faithful, naive, and innocent, rooted in patriarchal values, feels out of place in the context of the narrative. It detracts from the overall depth and authenticity of the storytelling.

Throughout the story, references to Laozi, Daoism, and Buddhist concepts such as karma add a layer of cultural relevance and inspiration. While this book may not shine in terms of literary quality compared to Qiu's other works, particularly in its portrayal of female characters, which is somewhat unsatisfactory, it holds immense vitality and potential influence as a work documenting the traumas of a significant era.

Reviewed by Mia Chen Ma.

Reviewed by Trina Garnett, 18/6/23

This is the latest in the Inspector Chen series by Qiu Xiaolong – his 13th novel starring the former Chief Inspector who has now retired but still advises the police on certain cases.

This is the latest in the Inspector Chen series by Qiu Xiaolong – his 13th novel starring the former Chief Inspector who has now retired but still advises the police on certain cases.

I was lucky enough to meet the author at the Book Reviewers Network event and he described it as his “most political book so far”. He wanted to write a novel about the pandemic and the impact of the Chinese Communist Party’s zero Covid policy on the people. He said: “If you want to write about a problem of a society, who would be more convenient than a detective?”

It's a subject close to the author’s heart, as you can tell from the book’s dedication: “to all the people that died and suffered in the pandemic, under the CCP’s inhuman zero-Covid policy, and the state surveillance and suppression worse than in 1984. The long, long victim list includes my mentor, Professor Li Wenjun.”

Love and Murder in the Time of Covid is set in the early days of the pandemic. If you’re familiar with the series, you’ll know that Inspector Chen Cao is a detective who loves his poetry (and who likes to quote it frequently!). At the start of the novel Chen is in Shanghai to work on a literary translation of classical Chinese poetry, when he is invited to work on an investigation of a potential serial killer in the city.

As a side project, Inspector Chen is asked by his friend Pang, Vice-Chairman of the Wuhan Writers Association, to help translate and disseminate the Wuhan Files to show what’s really happening in Wuhan – first-hand accounts from people living in Wuhan at the time, shared anonymously on messaging apps to try to bypass the ever-watchful eye of the authorities. The Author’s Note at the start of the book explains that this is a work of fiction, but “all the tragic incidents recorded in the Wuhan Files are real”.

So, after all this preamble, I was excited to read this novel to discover what “really” happened in Wuhan, and the start of a pandemic which touched us all. It’s a noble ambition but sadly, this book did not live up to such an epic promise – and how could it?

The story is set up as a detective story but quickly becomes more of a polemic. There are comparisons throughout to George Orwell’s 1984, which feel bolted on. The references are more general than specific and don’t feel like part of the story. The Wuhan Files are liberally quoted throughout – and these were some of the most interesting parts of the book. They are snippets of people’s lives and tragic events, but they are not full stories in themselves – and not part of this story either.

Chen and his assistant Jin are given relative freedom to go wherever they need to investigate the case, but they are watched by the ever-present Hou, a member of the CCP assigned to escort them everywhere and report back to the party. Hou was the most interesting character for me because it was ambiguous just how loyal he was to the party and how much he’d report back. It was telling that we never found out – nothing put Chen and Jin in enough jeopardy to test this out.

As for the detective side of the story, it is virtually non-existent and hinges on CCTV footage, the most basic of police checks. Given how many references there are to state surveillance in general it’s inconceivable that there wouldn’t be any – yet there is no reference to it for the first half of the book.

Another theme is the “will they/won’t they” relationship between Chen and his assistant Jin. There are oblique references to something that may or may not have happened between them during an encounter in the Yellow Mountains previously. However, it’s not made explicit and we don’t ever see much from Jin’s perspective either. She is portrayed as a capable and smart assistant, yet doesn’t seem to be more than a fantasy character when it comes to Chen contemplating their “relationship”, which makes the storyline feel one-side and outdated.

Chen refers to himself as “bookish” and this is a novel that certainly seems to be packed more with ideas than actions. Ultimately this wasn’t the right vehicle for such an ambitious story… Inspector Chen’s world feels too cosy to be affected by events even so close by – he and his family and friends are never in any real jeopardy and that doesn’t feel authentic.

Reviewed by Trina Garnett

Reviewed by Michelle Deeter, 2/6/23

Qiu Xiaolong’s latest Inspector Chen Cao book is not a page-turning whodunnit and is not a romance novel either, so readers are right if they think the title is a bit misleading. The story is set in the winter of 2019 to 2020, during the outbreak of Covid-19. The virus has already spread from Wuhan to other cities in China and is having a huge impact on all Chinese people. Three murders are committed near Renji Hospital in Shanghai, and Chen is compelled to solve the case even though he is technically on convalescent leave.

Qiu Xiaolong’s latest Inspector Chen Cao book is not a page-turning whodunnit and is not a romance novel either, so readers are right if they think the title is a bit misleading. The story is set in the winter of 2019 to 2020, during the outbreak of Covid-19. The virus has already spread from Wuhan to other cities in China and is having a huge impact on all Chinese people. Three murders are committed near Renji Hospital in Shanghai, and Chen is compelled to solve the case even though he is technically on convalescent leave.

The story has some nice parts. The description of youtiao (fried dough sticks) actually made me hungry, for example. But there were parts that I could not follow, and parts where I was not sure who the target reader was supposed to be. Is the story aimed at children who might not know much about Chinese culture or about Covid? Is the story aimed at adults, given that there are some vaguely romantic scenes in the story? Is the story aimed at people with Chinese heritage who want a record of what happened in a fictional setting? Or is the story just for people who enjoy poetry and literature? Given that every chapter starts with four quotes, and that Chen has a highly improbable ability to solve crimes using dreams and his knowledge of Chinese poetry, I think the latter makes the most sense. It’s not a story for people who enjoy fast-paced fiction.

There were a few parts that actually made me scream at the book. The narrator just told us what being invited to tea means, and then the book mentions it again in conversation on the same page. Repeating this phrase so soon after its introduction, especially in dialogue where it’s less believable, was frustrating and patronizing. Furthermore, some of the exposition was not doing anything for the story and that made me feel like the book was not edited for pacing. The potted history of Renji Hospital seemed forced. If some readers want to learn more about the hospital, they can look that up for themselves.

The phrase “little secretary” is particularly grating. Jin is a grown woman and Inspector Chen frequently reflects on how her insight is helpful to his investigation. Why do we have to keep emphasizing the fake backstory that she is only a little helper who provides sexual favours to Chen? Why does Jin call herself a little secretary when it would be degrading to do so? The book frequently mentions 1984 in an overt comparison of China to an Orwellian dystopia, but that does not mean that Jin and Inspector Chen have to mirror Julia and Winston.

At the end of the day, this book is just trying to do too much. It attempts to chronicle the times of Covid, give readers one last Inspector Chen adventure, increase interest with a serial murder case, explain Chinese culture-specific concepts like neighbourhood committees and medical disputes between healthcare professionals and ordinary Chinese, and re-introduce a potential romance that cannot work for some reason.

The title of the book shows how putting so many different elements into one book does it a disservice. I suspect that Qiu wanted to riff off of Love in the Time of Cholera by Gabriel García Márquez when he chose the title, because the former respects the latter as an author, but the two books are totally different. I cannot guess why the publishers allowed Qiu to pick a title that did not match more closely to the actual themes of the book. The upshot for the reader is a book that does not have a satisfying conclusion.

Reviewed by Michelle Deeter

Reviewed by Angus Stewart, 24/5/23

Qiu Xiaolong has said that Love and Murder in the Time of Covid is his most political and most literary book yet. That’s useful for me to know, because it is the first of his books that I’ve read. Qiu’s Inspector Chen series is now past its dozenth entry, but I suspect that I will be one of many late-entryists, drawn in by the magnetic pull of that ominous final word: Covid.

Qiu Xiaolong has said that Love and Murder in the Time of Covid is his most political and most literary book yet. That’s useful for me to know, because it is the first of his books that I’ve read. Qiu’s Inspector Chen series is now past its dozenth entry, but I suspect that I will be one of many late-entryists, drawn in by the magnetic pull of that ominous final word: Covid.

Chen Cao is – by this point in Qiu’s series – in quasi-exile from official police business, but is called in by the Shanghai municipal government to solve a string of murders. Meanwhile, the plague has arrived from Wuhan and citywide lockdown is imminent, leaving Chen to solve the case more-or-less remotely from an assigned hotel room. He works with subterfuge (and curious ease, it must be said) through various contacts – foremost his secretary.

The political angle in the book is no mystery. Qiu Xiaolong lives in the USA and writes in English, leaving him free to make it abundantly clear that whatever patience he (and the good detective) had with Xi Jinping’s brand of party rule is gone. In this novel, Shanghai’s policy of total technological lockdown often feels like a jump-off point to exposit as many facets of CCP authoritarianism as possible. Xi is never named, but does get referred to as a pig several times. Qiu has said he intended this as a literary reference to 1984. I don’t wish to invalidate the author’s feelings – it’s his homeland, and indeed his hometown – but I definitely would have preferred a few lethally-timed sniper rifle blasts rather than the wild shooting from the hip we get here, especially in a literary genre whose worth is often measured by its precision.

Now, about that secretary. She’s called Jin, she’s much younger than Chen, and across the novel she teeters on the edge of a will-they-won’t-they romance with her boss. Her willingness to comply with everything Chen says left me feeling a little uncomfortable, frankly, though the meditations that their age gap provokes on firstly the dubious patriarchal entanglements of modern Chinese officialdom and secondly the bittersweet curse of time and aging are – I’d say – two of the book’s relative strengths. A little more angst, a little more tension, and I’d have been truly intrigued. Also worth a mention is Chen’s minder from the municipal government, Hou: a genuinely interesting character, whose mental interior and true intentions Qiu never discloses. We cannot know if his grin is pained-yet-genuine, or that of a watchful shark – exactly the sort of figure we need in a novel taking aim more at the Xi-era than the Covid-era.

Qiu adds ‘literariness’ to the mix quite directly, through translations of Tang poetry and quotes from the likes of Immanuel Kant, sage Confucius, and TS Eliot. What these had to do with the story tended to escape me, though less so for the quotes he draws from a fictional ‘Wuhan file’, which sounds not entirely unlike Fang Fang’s explosive Wuhan Diary – a nonfiction text that I’d direct readers curious about Covid and lockdown in China to before this novel, if only because Fang Fang’s account isn’t preceded by twelve other books.

Reviewed by Angus Stewart

Reviewed by Zahra Raja, 22/5/23

The latest instalment in the incredibly popular Inspector Chen series, this novel is set at the height of the pandemic in China and follows Chen as he is forced to solve a serial murder case during the CCP’s zero Covid policy. The killings are causing the CCP to attract unwanted attention and criticism of the way the it is handling the pandemic at large, hence their recruitment of the formerly disgraced Chen as a consultant to the case.

The latest instalment in the incredibly popular Inspector Chen series, this novel is set at the height of the pandemic in China and follows Chen as he is forced to solve a serial murder case during the CCP’s zero Covid policy. The killings are causing the CCP to attract unwanted attention and criticism of the way the it is handling the pandemic at large, hence their recruitment of the formerly disgraced Chen as a consultant to the case.

In the preface, Qiu dedicates the novel to those who died and suffered in the pandemic under this policy, and also acknowledges his debt to the “netizens” who reported on the events during this period, as his novel could not have been written without them. Indeed, as someone who had only been scanning the news during the pandemic, it was a real shock to learn of the depth of suffering that ordinary Chinese people were subjected to under this policy. While there are those that might argue that people would be better off reading The Wuhan Diary in order to get a better understanding of what transpired rather than a work of fiction such as Love and Murder, for those who weren’t glued to the news during the pandemic and came across this novel by chance or as a loyal reader of the Inspector Chen series, it serves as an important first step to understanding the social and political ramifications of the zero Covid policy. Ultimately, it is meant to open the eyes of a Western audience, not a Chinese one.

The novel opens with ex-Chief Inspector Chen (who doubles as a poet and translator in his spare time) having a mild existential crisis and taking trips back into memory lane. We don’t learn why he is now ex-Chief, but this may have been revealed in the previous novel, which I haven’t read. He is approached by an old friend who begs him to translate a document called “The Wuhan File”, which is a diary of life under the zero Covid policy, and the collateral damage wrought as a result. Chen is reluctant initially as he has his mother to think about and he has a healthy dose of self-preservation, attempting to live within the narrow parameters drawn up for him. I found this to be rather refreshing and honest in a main character – we can’t all be the quintessential devil-may-care hero.

Admittedly this doesn’t last very long – it’s not long before he’s approached by a high-level party cadre to investigate a string of murders in a hospital during the height of the zero Covid policy, and given his position back. He naturally does not have a choice in the matter, and subsequently agrees to translate "The Wuhan File" in retaliation as he goes deeper into the case and starts to understand the scale of the cover-up from the authorities. This decision is only cemented when he cracks the case but is forced to cover up the real motives for the killings, which turn out to be retaliation for preventable deaths brought about by the policy.

It is here we fully understand the title; it refers not to Chen and the romance with his secretary Jin, rather to the main perpetrator of the crimes whose wife was refused admittance to several hospitals under the zero Covid policy and died outside the door of the last in front of her husband. The irony is that Jin’s father, who has an asthma attack, is admitted immediately to hospital despite not having a green Covid test, which goes to show just how corrupt the system is in favour of the few elite.

Ultimately, while the crime and the solving of it are important plot points, they almost take a backseat to the horror-scape of China during the zero Covid policy. The most poignant parts of the novel for me were “The Wuhan File” extracts; they brought the horror of the policy to life, with stories of women haemorrhaging babies on hospital doorsteps, a mother and daughter falling to their deaths trying to climb out a window to escape a locked complex to reach hospital and worse. Tragically, all these attempts were doomed to failure without the requisite green Covid test taken within the previous 24 hours.

This novel is an important piece of fiction in memorialising the collateral damage from the zero Covid policy, and as a relatively short read of 200 pages I would encourage anyone wanting to know more to pick it up.

Reviewed by Zahra Raja