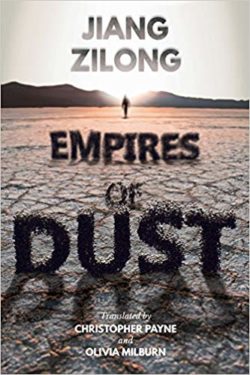

Empires of Dust, by Jiang Zilong

translated by Christopher Payne and Olivia Milburn

translated by Christopher Payne and Olivia Milburn

ACA Publishing, 2019

Publisher's Blurb

Amidst the maelstrom of Communist China’s rocky beginnings, Guojiadian, a tiny hamlet situated on salty ground in the rural northeast where nothing grows, must forge a path through the turbulence - both physical and political - threatening to return the windswept village to the dust from which it emerged.

Amongst the long-suffering village inhabitants lives Guo Cunxian, a man of rare ability trapped in an era of limitations. His quest for a better future for him and his family pits him against the jealousy of his peers, the indifference of his superiors and even the seemingly cursed earth upon which he resides.

In a decades-long journey filled with frustration and false starts, they eventually rise to dizzy heights built upon foundations as stable as the dust beneath their feet and the mud walls which shelter them.

But will their sacrifices along this tortuous path be in vain…?

Reading Chinese Network Reviews

Reviewed by Kevin McGeary, 17/4/19

With a famine, self-inflicted political chaos, and the fastest-growing economy in history, the second half of China’s twentieth century lends itself to the telling of extraordinary stories.

With a famine, self-inflicted political chaos, and the fastest-growing economy in history, the second half of China’s twentieth century lends itself to the telling of extraordinary stories.

One of the most revered literary figures to have portrayed this period in writing is Jiang

Zilong, whose latest novel – his first in over ten years – is a vast tome that spans some four decades of this remarkable period.

Set in the fictional village of Guojiadian, Empires of Dust chronicles the rise and fall of Guo Cunxian, who goes from simple and impoverished youth to respected ‘peasant emperor’. Guo Cunxian embodies both the noble and diabolical characteristics that have facilitated China’s rise.

Early in the novel, having made a relative fortune with one of the few methods available to him (coffin-making), Guo Cunxian resists the highly tempting sexual advances of single mother Sister Liu. By the novel’s midway point, he pulls his mistress Meitang aside for an intimate moment in a cemetery among the burial mounds.

When a young Guo Cunxian is punished by having to do some labour, he secretly enjoys it, musing: “The world became simple when all a man had to do was work. Physical exertion had wiped his mind clean and settled the problems plaguing his heart.” Later on, Guo, like so many other powerful officials and businessmen, is in jail and has no way of escaping the reality of his wrongdoings.

Told with an omniscient narrator, the book dips into the thoughts and feelings of all the major characters, and also contains musings on everything from the nature of cursing to the relationship between sex and marriage. From start to finish, Jiang Zilong’s mastery of scene creation inspires awe.

Guo Cunxian’s first encounter with his beguilingly demure wife Xuezhen, his monologue describing on television and to an audience of powerful officials the rise of Guojiadian, and a scene in which an officer observes that the years have caused Guo’s laugh lines to ‘set in patterns of arrogance and disdain’ are all highlights. On top of this, Jiang Zilong has a particular talent for sex scenes.

The scenes between Guo and Xuezhen, Guo and Meitang, and one in which a man is caught by the father of the girl he is trying to romance, are all highly quotable. A line from another sex scene involving members of the supporting cast, is: “His orgasm tore him from his body, his spirit sailed and then his body slumped, sated and fulfilled”. A lesser writer would be a shoo-in for The Bad Sex Award if they had attempted the same things.

The book’s major flaw is its length. Toward the end, Guo Cunxian is forced to listen to two stories that analogize his rise and foresee his fall. In this sense, Jiang Zilong is a victim of his own success, as the editors of a less eminent author probably would have cut this and other of the more heavy-handed sections.

Also, the front of the book really could have done with a full Cast of Characters section so the reader could occasionally go back and reference who was who. The cast is massive and some characters have names that appear similar at first glance, eg Guo Cunxian, Guo Cunyong, and Guo Cunzhi. When it is published in North America, editors may also need to consider the use of profanities including ‘ponce’ and ‘bollocks’.

In spite of this, Empires of Dust is a sweeping story with lots of valuable things to say about its characters and settings. Human nature never changes, “land is the easiest and most difficult thing to understand”, and politics never alters the fact that society is rife with class divisions.

As an old man, Guo Cunxian is subjected to a police interrogation of such insight and intensity, it is almost as if he is meeting his maker. Much of what the officer says of Guo’s mistakes and misdeeds can also be said of the Communist Party.

Reviewed by Kevin McGeary