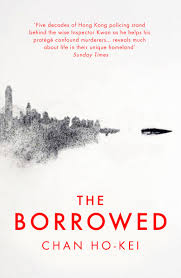

The Borrowed by Chan Ho-kei

translated by Jeremy Tiang

Head of Zeus, 2018

Publisher's Blurb

From award-winning Hong Kong writer Chan Ho-kei, The Borrowed tells the story of Kwan Chun-dok, a Hong Kong detective  whose career spans fifty years of the territory’s history. A deductive powerhouse, Kwan becomes a legend in the force, nicknamed “the Eye of Heaven” by his awe-struck colleagues. Divided into six sections told in reverse chronological order—each of which covers an important case in Kwan’s career and takes place at a pivotal moment in Hong Kong history from the 1960s to the present day—The Borrowed follows Kwan from his experiences during the Leftist Riot in 1967, when a bombing plot threatens many lives; the conflict between the HK Police and ICAC (Independent Commission Against Corruption) in 1977; the Tiananmen Square Massacre in 1989 to the Handover in 1997; and the present day of 2013, when Kwan is called on to solve his final case, the murder of a local billionaire, while Hong Kong increasingly resembles a police state. Along the way we meet Communist rioters, ultra-violent gangsters, stallholders at the city’s many covered markets, pop singers enmeshed in the high-stakes machinery of star-making, and a people always caught in the shifting balance of political power, whether in London or Beijing–all coalescing into a dynamic portrait of this fascinating city.

whose career spans fifty years of the territory’s history. A deductive powerhouse, Kwan becomes a legend in the force, nicknamed “the Eye of Heaven” by his awe-struck colleagues. Divided into six sections told in reverse chronological order—each of which covers an important case in Kwan’s career and takes place at a pivotal moment in Hong Kong history from the 1960s to the present day—The Borrowed follows Kwan from his experiences during the Leftist Riot in 1967, when a bombing plot threatens many lives; the conflict between the HK Police and ICAC (Independent Commission Against Corruption) in 1977; the Tiananmen Square Massacre in 1989 to the Handover in 1997; and the present day of 2013, when Kwan is called on to solve his final case, the murder of a local billionaire, while Hong Kong increasingly resembles a police state. Along the way we meet Communist rioters, ultra-violent gangsters, stallholders at the city’s many covered markets, pop singers enmeshed in the high-stakes machinery of star-making, and a people always caught in the shifting balance of political power, whether in London or Beijing–all coalescing into a dynamic portrait of this fascinating city.

Tracing a broad historical arc, The Borrowed reveals just how closely everything is connected, how history always repeats itself, and how we have come full circle to repeat the political upheaval and societal unrest of the past. It is a gripping, brilliantly constructed novel from a talented new voice.

Reading Chinese Network Reviews

Reviewed by Mia Chen Ma, 10/7/23

Chan Ho-Kei's The Borrowed is an excellent collection of crime novellas. Exploring six gripping cases that span Kwan Chun-dok's remarkable fifty-year career, the anthology takes readers on a captivating journey through Hong Kong's tumultuous history. From the Leftist Riot in 1967 to the 1977 conflict between the HK Police and ICAC (Independent Commission Against Corruption), and encompassing pivotal moments such as the Tiananmen Square Demonstration in 1989 and the Handover in 1997, each story serves as Chan's contemplation of a specific chapter in Hong Kong's history.

Chan Ho-Kei's The Borrowed is an excellent collection of crime novellas. Exploring six gripping cases that span Kwan Chun-dok's remarkable fifty-year career, the anthology takes readers on a captivating journey through Hong Kong's tumultuous history. From the Leftist Riot in 1967 to the 1977 conflict between the HK Police and ICAC (Independent Commission Against Corruption), and encompassing pivotal moments such as the Tiananmen Square Demonstration in 1989 and the Handover in 1997, each story serves as Chan's contemplation of a specific chapter in Hong Kong's history.

It is intriguing to discover that Chan Ho-Kei, a Hong Kong native, has held various roles such as software engineer, scriptwriter, game designer, and comic magazine editor. This diverse experience is interwoven into Chan's unique storytelling, blending mystery, suspense, and Asian cultural elements seamlessly into the narratives.

Among the six stories, my personal favorites are "The Truth Between Black and White (2013)" and "Prisoner's Honour (2003)". In the first story, the core message revolves around the contrast between adhering to rules and pursuing justice. The narrative explores the notion that disregarding unjust rules can be justified if it prevents harm to innocent individuals or hinders the course of justice. As the plot unfolds, secrecy becomes a central element, making the events even more challenging to decipher. The confession of Wing-yee early on raises questions about his involvement in the murder—is he the perpetrator or protecting someone? Intriguingly, the desire to prove our own hypotheses often leads us into further puzzles. The story also delves into the complexities of the typical Asian father-son relationship, adding another layer of understanding to the case. However, the incorporation of cultural elements often plays a vital role in further misleading readers away from the truth.

I particularly like how Chan skilfully presents one interpretation that makes you believe you have solved the case, only to introduce another puzzle soon after. Initially, the author showcases how technological advancements improve the investigative capabilities of individuals. For instance, the comatose detective Kwan utilizes brainwave synchronization to solve cases, highlighting the potential of technology in crime-solving. However, the author takes a sudden turn in the narrative, ruthlessly ridiculing society's blind idolization of technological prowess. This shift challenges the notion that technology alone can solve crimes and exposes the inherent dangers of unquestioning faith in its abilities. Interestingly, the author reveals that manipulating people's blind trust in technology becomes a crucial factor in ensnaring the true culprit. This clever twist demonstrates the author's critique of society's dependence on technology and how it can be exploited for nefarious purposes.

The second story, “Prisoner's Honour (2003)”, showcases Superintendent Kwan's strategic scheming, reminiscent of tactics from Sun Tzu's "The Art of War". Deception takes center stage as the crime scene and sequence of events are manipulated beyond recognition. Inspector Lok, the protagonist, unwittingly becomes part of the plan, highlighting the interconnectedness of the stories within the anthology. The story reflects the importance of deception and strategic manipulation in cracking crime cases, akin to warfare. The key lies in confusing the criminals, like Boss Chor, preventing them from understanding our true intentions. Deception forms the foundation, creating the perception of weakness when we are strong, appearing inactive when we are actively employing our forces, and making the criminals believe we are far away when we are near, and vice versa. Success lies in engaging criminals based on their expectations and confirming their projections, establishing predictable patterns of response while patiently awaiting the opportune moment—the extraordinary event they cannot anticipate. Additionally, Confucian values are intertwined with the characterization of the Hong Kong police force, emphasizing the protection of human life and the significance of the weak, adding depth and moral complexity to the narrative.

Throughout The Borrowed, Chan Ho-Kei weaves an intricate tapestry of crime, history, and human nature. The anthology skilfully incorporates elements of strategy, deception, Confucian values, and Hong Kong's socio-political climate, offering readers a rich and thought-provoking reading experience. It is a must-read for fans of crime fiction and those interested in exploring the intersection of history and mystery. Chan Ho-Kei's storytelling prowess shines through, leaving readers engrossed and eagerly turning the pages until the final revelation.

Reviewed by Mia Chen Ma

Reviewed by Trina Garnett, 18/6/23

It is not surprising to learn that The Borrowed by Chan Ho-Kei was optioned by film director Wong Kar Wei. It feels like it could be a TV series because of its unusual structure. This is a novel in six parts – effectively six novellas, where the common strand is the “genius detective” Inspector Kwan Chun-Dok.

It is not surprising to learn that The Borrowed by Chan Ho-Kei was optioned by film director Wong Kar Wei. It feels like it could be a TV series because of its unusual structure. This is a novel in six parts – effectively six novellas, where the common strand is the “genius detective” Inspector Kwan Chun-Dok.

In the English translation by Jeremy Tiang, the six sections are simply named after a year, which are all key dates in the history of Hong Kong where the novel is set. The years are in reverse chronological order, from 2013 to 1967. In the original, Jeremy has explained, the section headings are in different languages which reflect the changing governance of Hong Kong over time, with two chapter headings in Chinese, two in both English and Chinese, and two in English.

Each section narrates a different crime story in the city, with a changing cast of characters and social setting. If you know Hong Kong well there are more “Easter eggs” for you here too. As the author explains in his Afterword, some of the characters and locations are repeated in different guises, but you’d have to be a local to spot them all and recognise how they’ve changed over the decades.

This is clearly a novelist who likes to play around with structure and puzzles. It is not surprising to learn the author has worked as a software engineer and games designer. Each section is also very different in tone, as if he is also exploring different crime genres with each.

I loved the quirkiness of the opening section – the legendary detective in a coma in the back of the hospital room, apparently dictating “yes” or “no” answers directly from his brain via cutting edge technology. We are in dystopian fiction here, as well as the “locked-room” Agatha Christie-style crime genre, where all the suspects are gathered before the inspector solves the case. Yet it also works as a metaphor – the genius detective present but not conscious as the younger policeman carries out his duties. What kind of policeman will he be – will he, like his mentor, bend the rules for the greater good, or will he follow orders? This is one of the main themes of the book.

It is not immediately obvious to the reader how the novel is constructed, which is disconcerting at first. You could wrongly assume the “main character” is Sonny Lokas he is the main narrator and the first person we meet. But this is the peak of his story arc. Starting section two feels like we’re reading a new book.

Because of this reverse chronology we don’t get a sense of character development – we are told that Inspector Kwan is a genius detective but we haven’t seen why, so his reputation precedes his actions. In fact the book is mainly made up of his clever deductions rather than actions. We don’t get a sense of Kwan as a rounded character, we don’t see much of his personal life, especially in later years.

And female characters are notable by their absence. I can only think of two in the whole book and both are fairly two-dimensional plot devices: one is a victim motivated by revenge; the other is a “bad mother”.

Overall The Borrowed didn’t work for me as a novel. The structure didn’t help sustain my interest in the characters and I didn’t find anything emotionally gripping enough to keep me hooked.

Reviewed by Trina Garnett

Reviewed by Michelle Deeter, 2/6/23

If you’re looking for a crime novel that drops you right in the middle of Hong Kong, look no further. The setting is vividly portrayed, the stories are well-crafted, and each story has its own twist. Despite surprising me again and again, this book follows the conventional rules about detective fiction that were developed in the Golden Age of Crime Fiction in the 1920s and 1930s. That means that every story, and the book as a whole, has a satisfying ending.

If you’re looking for a crime novel that drops you right in the middle of Hong Kong, look no further. The setting is vividly portrayed, the stories are well-crafted, and each story has its own twist. Despite surprising me again and again, this book follows the conventional rules about detective fiction that were developed in the Golden Age of Crime Fiction in the 1920s and 1930s. That means that every story, and the book as a whole, has a satisfying ending.

The stories go backwards in time, each using a different framing. It starts with a locked room murder in 2013, giving readers who may be unfamiliar with Hong Kong geography and culture an easy place to acclimatize. A funny trick of using a computer to get one of the suspects to confess was delightful, combining a science fiction element with classic whodunnit elements.

The second story involves Inspector Lok being frustrated by a lack of success in a drug raid. This chapter is set in 2003 and the story zooms out to include triads, office politics, and the difficulties of being a team commander when things are not going well. Lok unburdens himself to his mentor, Kwan Chun-dok, saying how frustrating the last few weeks have been. Kwan replies, “If you couldn’t deal with a little setback like this you’d really be unfit to take command.” Lok does his best not to show his disappointment to his subordinates and tells them, “We just ran into a bit of bad luck, we’ll do better next time.” Eventually, Lok sees why his operations have been so unsuccessful, and the advice that Kwan gave him makes more sense. When Lok meets one of the victims of the drug crime he wants to promise that he will help her seek justice, but instead of making an empty promise he says nothing because he “knew that justice consists of actions, not words.”

The third story jump further back, to 1997. This is supposed to take place on Kwan’s last day of service, but it is also set close to the time of the Hong Kong handover, so the important moments in Hong Kong’s history make a subtle appearance of Kwan’s incredibly tiring day. But even though the criminals are frightfully clever, Kwan always gets them in the end. Two storylines that seem unrelated come together and Kwan tricks a criminal to solve the case, to Lok’s surprise.

Then we have three more stories, taking place in 1989, 1977, and finally 1967. Each one introduces new characters, but the stories usually include Kwan which provides some continuity. The magnificent city of Hong Kong is always at the forefront of the story. The scavenger hunt story is a great example of all the tiny little details coming together for the kidnapping and the investigation to be a success.

Overall, I love how people are working as a team to get their answer. Even when some of the advice is fairly predictable (e.g. “Believe in yourself. You were promoted because those above were confident of your abilities. Just trust in yourself, and you’ll be a good leader.”) these parts of the book are part of the charm. These somewhat sappy moments of cop mentor talking to optimistic young cop are part of the crime fiction genre, at least in the books that I have read. The story should begin with a transgression and a chaotic society and it should end with order being brought to society.

More than anything else, I love how Hong Kong is portrayed. Everything, from the names and nicknames of minor characters, down to the number of entrances an old building has, is carefully thought out. The consequences of each character’s actions all fit together to form an excellent plot. It works so well that the book is enjoyable even on the second or third read.

The translation is smooth and keeps the excitement levels high. There are particular lines where a Chinese idiom is used, but it blends in so well, it might pass by without being noticed. For example “they could only treat the symptoms but not the cause” (治标不治本) is a Chinese idiom that might not be regularly used in English but is fairly simple to understand, because the metaphor is crystal clear. The translator was able to keep the metaphor without causing any detriment to the storyline. Another well-known Chinese phrase, 纸包不住火, was rendered as “As the saying goes, you can’t hide fire with paper.” This phrase was only slightly changed from the Chinese and fronted with a “as the saying goes” to signal what type of information was coming next. I really thought this was a cool feature of the book, something that made it feel more authentic without being anthropological or othering. I can tell that the translator has been to Hong Kong because all of the details tally perfectly. It really feels like the reader is in the midst of the action.

This is a book to read and even re-read, especially for anyone who is a fan of classic crime fiction.

Reviewed by Michelle Deeter

Reviewed by Angus Stewart, 24/5/23

Chan Ho-kei is hyper-prolific, and writes across several genres. Go looking for his work in English translation, however, and you’ll find only two books, each filed under one genre: detective fiction. (Hardened online literature sleuths may also dig up a translation of his short story Seeing Ghosts, hosted on this very site.)

Chan Ho-kei is hyper-prolific, and writes across several genres. Go looking for his work in English translation, however, and you’ll find only two books, each filed under one genre: detective fiction. (Hardened online literature sleuths may also dig up a translation of his short story Seeing Ghosts, hosted on this very site.)

The two translated books are Second Sister, and our text-in-question: The Borrowed. Both books (they’re Chan’s only crime novels, funnily enough) rely on the interplay between two sides of a binary commonly employed in East Asian framings of crime fiction: a ‘classic crime’ style that focuses on pure logical puzzlework, and a ‘social’ style that builds out psychology and setting to cast a critical eye over society and its conditions. There’s no wrongdoing in utopia, after all.

Chan Ho-kei’s hometown is Hong Kong, an incredible city but indeed no utopia – not now and not ever, as The Borrowed aptly demonstrates. Fans of The Wire may well find something to relish here, because just as that show cast the city of Baltimore in the 00s as its main character by dedicating each season to a different segment of the beleaguered cityscape and its underworld, The Borrowed paints a picture of Hong Kong that extends through time by tracing the career of a detective backwards through six not-particularly interlinked novella-sized cases. We start in ‘the present’ – more or less – and leapfrog through eras bookmarked by home rule, handover, and British colonial government to end on the eruption of leftist, anticolonial dissent that challenged that government in the 1960s. The book’s translator, Jeremy Tiang, has indicated than the author knows exactly what he is doing in highlighting these particular snapshots of Hong Kong history. Under the eye of the reader, neither crime nor context ought to be exempt from interrogation.

For me, the weak link in The Borrowed is the cast. Nobody feels more than a few inches deep, and our detective – Sonny Lok – is as unbeatable as he is plain. The detective in Second Sister, by comparison, is unbeatable too – but he’s a strange, egotistical, abrasive specimen; and thus a great foil to that novel’s gentler protagonist.

The strong link in The Borrowed is power. Characters here are not ciphers, but envoys for the tidal surge and retreat of massive forces: the triads, the police, the state, the empire, the cultural revolution. Certain players may take the dominant position in Hong Kong and hold it through deadlock, but here we see tension and flux remain at play, as unbanishable laws driving forward the lives and crimes of the city’s ocean of inhabitants.

This version of the story, the abstracted long view, takes on sharper form with each turn of the page. For the first half of The Borrowed, the reader will likely be deriving most of their frisson from the minutia of the crimes and clues that Sonny Lok grapples with. This, combined with the unique texture of Hong Kong constructed between the lines, makes for a reasonably entertaining ride. It’s Chan Ho-kei’s backward flight through the chapters of history, I’d argue, that leaves a trail more worthy of investigation.

Reviewed by Angus Stewart

Reviewed by Zahra Raja, 22/5/23

The Borrowed follows the life of Kwan Chun-Dok, who is a legendary inspector in Hong Kong, with a 100% success rate and genius powers of deduction that he uses to crack cases. The novel spans six cases in reverse chronological order, from his death in the first story in 2013 to a defining moment at the start of his career in the 1960s which shapes his moral philosophy for the rest of his life. Each case is set against during a defining moment in Hong Kong history, from Handover in 1997 to British colonial rule earlier on the century. While these events are generally not the focus of the chapters, they do subtly influence the story, and it was interesting to see the political and social portrait of Hong Kong painted throughout the decades in all its glory and corruption. The title is a reference to Frank Welsh’s A Borrowed Place: The History of Hong Kong which is a history of Hong Kong but focused almost entirely on British interests; Chan clearly wanted to make a point here, and The Borrowed is entirely from Kwan or his protégé Sonny Lok’s perspective, with British characters featuring infrequently and rarely central to the story.

The Borrowed follows the life of Kwan Chun-Dok, who is a legendary inspector in Hong Kong, with a 100% success rate and genius powers of deduction that he uses to crack cases. The novel spans six cases in reverse chronological order, from his death in the first story in 2013 to a defining moment at the start of his career in the 1960s which shapes his moral philosophy for the rest of his life. Each case is set against during a defining moment in Hong Kong history, from Handover in 1997 to British colonial rule earlier on the century. While these events are generally not the focus of the chapters, they do subtly influence the story, and it was interesting to see the political and social portrait of Hong Kong painted throughout the decades in all its glory and corruption. The title is a reference to Frank Welsh’s A Borrowed Place: The History of Hong Kong which is a history of Hong Kong but focused almost entirely on British interests; Chan clearly wanted to make a point here, and The Borrowed is entirely from Kwan or his protégé Sonny Lok’s perspective, with British characters featuring infrequently and rarely central to the story.

While I found it difficult to believe a genius such as Kwan could exist, suspension of disbelief is part of the experience and doesn’t detract from how well the crimes are planned, executed and then solved. The author is very good at leading the trajectory of the crime-solving down a path, and then yanking out the rug from underneath that path, to the point where I started to have trust issues with Kwan’s deductive reasoning in the early part of each case. We see a more human side to Sonny who grows under his mentor’s guidance and suffers with the same imposter syndrome that many readers will relate to, so it is satisfying to see how he develops into a successful detective in his own right.

The final plot twist in the last story (or first chronologically) is particularly good, and brings the stories full circle – Kwan was always a superb policeman, but when faced with the question “are you loyal to the colonial government or to us Hongkongers?”, it is this moment that really shapes his philosophy and attitude to his work for the rest of his life; that ultimately the rules may need be bent sometimes for lives to be saved and for justice to prevail. There is a moment in this section where the final case comes full circle to the first, which makes for a satisfying conclusion. Overall a thoroughly enjoyable read and a great introduction to the world of crime fiction.

Reviewed by Zahra Raja

Reviewed by Catherine Shipley, 22/12/18

There are certain genres of novels that either attract enthusiasts, who hungrily rush from one book to the next, or readers who have stumbled across a book by accident and remain ambivalent towards the genre after reading it. I have always believed detective novels to be such a genre and myself to be the ambivalent (at best) reader. For this reason, I was skeptical about reading The Borrowed.

There are certain genres of novels that either attract enthusiasts, who hungrily rush from one book to the next, or readers who have stumbled across a book by accident and remain ambivalent towards the genre after reading it. I have always believed detective novels to be such a genre and myself to be the ambivalent (at best) reader. For this reason, I was skeptical about reading The Borrowed.

For the first page or two I rushed to assume that I could expect a familiar formula - there would be a crime, page after page of clues and red herrings, until finally, at the end of the book, the crime would be solved and I would attempt to be surprised. The novel would be peppered with lukewarm characters, with the exception of a brilliant, but otherwise nondescript, detective.

A page or two later I was taken aback. Something completely unexpected had happened. Where on earth was this story going to lead? I couldn't possibly imagine. It did not resemble my formula in the slightest.

The Borrowed is a selection of short stories which are related to each other. This offers the reader lots of variety and a chance to view Hong Kong police at work in different contexts.

Most stories feature Superintendent Kwan Chun-dok and his protégé, Sonny Lok. Kwan's crime-solving foresight is somewhat fantastical but that is beside the point. We are swept up by the fast-paced, action-packed narrative and barely have time to digest one event before the next adventure begins.

The Borrowed educated me as much as it entertained me. Although a work of fiction, it happens to provide an interesting insight into different periods of Hong Kong's history, focusing on the Hong Kong police force. Most readers will be aware of the territories handover to the Chinese government in 1997 and the troubles that followed. The Borrowed reminds us that things weren't so rosy under the British either. Talented Hong Kong police officers rising up through the ranks inevitably had to report to white British officers, to whom they had to communicate in English. No matter how long the British had spent in Hong Kong or how many Chinese employees they managed, they didn't learn Cantonese. They remained in a superior position, with no questions raised as to whether a local may be better placed to carry out their work.

One story describes a period of unrest under British rule, during which Hong Kongers could not avoid picking sides between the British and the mainland Chinese. Ultimately, neither side had Hong Kongese interests at heart. They appeared to be the only victims of the inescapable conflict.

As Chan Ho-Kei mentions in the Afterword, each reader will interpret the book in their own way. I was left with a feeling of frustration regarding the identity of Hong Kongese people. They were certainly not British, nor mainland Chinese. They definitely had a unique identity of their own but at every turn seemed to have been prevented from defining it.

I noticed that in addition to the locations mentioned in the novel, some of the crimes appeared to be based on reality. Reading this book, I couldn't help but draw conclusions about Hong Kong; its gangs, its police force and its politics. It was refreshing to be entertained but to be given something (crime-solving aside) to think about at the same time.

Reviewed by Catherine Shipley

Reviewed by Sean Barrs, 11/12/18

The Borrowed is an engaging book that chronicles the life of an extraordinary Hong-Kong based detective by piecing together six novellas, each reporting on an intriguing case, that slowly reveals exactly how talented he is.

The Borrowed is an engaging book that chronicles the life of an extraordinary Hong-Kong based detective by piecing together six novellas, each reporting on an intriguing case, that slowly reveals exactly how talented he is.

By doing so, the book navigates its way through the history of Hong Kong policing. It details how it has changed and developed over the years, by going backwards in time we see how far things have come. And this is a real clever technique, not one I have seen before in fiction. The book begins with its protagonist on death’s door, unable to work senior inspector Kwan Chun-dok can only consult junior detectives through the help of some rather advanced technology that allows him to communicate despite being in a coma. Regardless, he still proves a great help in the case. Not even death can stop him.

As the book goes back in time, we see the inspector in all his glory. He has the skill and intelligence to match either Sherlock Holmes or Hercule Poirot, earning the alias “The Eye of Heaven” because of his intuitive perceptiveness. Like the two great investigators, he is willing to look outside of the law to find his solution when necessary and he is always ahead of his quarry. The reader is not aware of all the facts, but Kwan Chun-dok has already pieced the clues together. What follows is a big reveal at the end of most of the sections. Each part is a little different and each full of mystery and intrigue, and they are all genuinely exciting to read about.

Other than exceling at characterising the detective, and filling the novellas with heaps of suspense, Chan Ho-Kei’s time shifts also provide a social picture of China and the people that have lived there over the decades. This is more than just a thrilling detective drama. The story goes back by fifty years, chronicling the aftermath of communism, poverty and captures the brutality of vicious gangs like the triads. Kwan Chun-dok navigates his way through the social issues as he tries to solve his cases. The book does wonders at capturing the city, a city that is rich in its own culture. And the culture is varied. There is no unifying sense of identity, but a collection of smaller spaces that are linked to the history of China as whole but together help to create part of the present.

Chan Ho-Kei does not tell his story with flowery or glittery prose, he is certainly not a flashy writer, but what he does do is report exactly on the things his characters see, think and smell. It gives a sense of realness to the writing, a sense of realness to the city and the people that inhabit it. He also has natural ear for dialogue and all the clumsiness can come with real speech. Through his words, I feel like I have walked the streets and witnessed how alive and fast Hong Kong can be. And, for me, that’s a real feat of writing. It is totally immersive. The Borrowed will appeal directly to those that like detective novels, and to those that want to learn a little bit more about China.

Reviewed by Sean Barrs