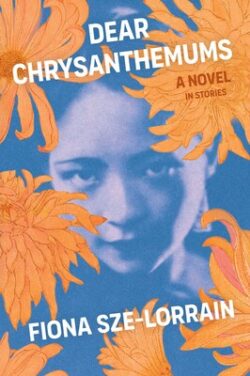

Dear Chrysanthemums, by Fiona Sze-Lorrain

Scribner, 2023

Publisher's Blurb

A startling and vivid debut novel in stories from acclaimed poet and translator Fiona Sze-Lorrain featuring deeply compelling Asian women who reckon with the past, violence, and exile—set in Shanghai, Beijing, Singapore, Paris, and New York.

A startling and vivid debut novel in stories from acclaimed poet and translator Fiona Sze-Lorrain featuring deeply compelling Asian women who reckon with the past, violence, and exile—set in Shanghai, Beijing, Singapore, Paris, and New York.

“Cooking for Madame Chiang,” 1946: Two cooks work for Madame Chiang Kai-shek and prepare a foreign dish craved by their mistress, which becomes a political weapon and leads to their tragic end. “Death at the Wukang Mansion,” 1966: Punished for her extramarital affair, a dancer is transferred to Shanghai during the Cultural Revolution and assigned to an ominous apartment in a building whose other residents often depart in coffins. “The White Piano,” 1996: A budding pianist from New York City settles down in Paris and is assaulted when a mysterious piano arrives from Singapore. “The Invisible Window,” 2016: After their exile following the Tiananmen Square massacre, three women gather in a French cathedral to renew their friendship and reunite in their grief and faith.

Evocative, vivid, disturbing, and written with a masterly ear for language, Dear Chrysanthemums renders a devastating portrait of diasporic life and inhumanity, as well as a tender web of shared memory, artistic expression, and love.

Reading Chinese Network Reviews

Reviewed by Catherine Shipley, 24/2/24

It is challenging to sum up Dear Chrysanthemums. The stories provoke so many thoughts and feelings that it is not be possible to describe them all here. The structure of the novel is unique in that, although it is separated into chapters, each chapter consists of short stories. Each story is clearly dated with the year(s) in which the events took place. The chapters begin with quotations, such as that at the beginning of the novel, ‘Secrets on earth, thunder in heaven.’ I felt that the effect of this and the way in which the stories were told lent a

It is challenging to sum up Dear Chrysanthemums. The stories provoke so many thoughts and feelings that it is not be possible to describe them all here. The structure of the novel is unique in that, although it is separated into chapters, each chapter consists of short stories. Each story is clearly dated with the year(s) in which the events took place. The chapters begin with quotations, such as that at the beginning of the novel, ‘Secrets on earth, thunder in heaven.’ I felt that the effect of this and the way in which the stories were told lent a

poetic feel to the book.

Dear Chrysanthemums recounts the darkness of certain events in modern Chinese history, such as the behaviour of Red Guards during the Cultural Revolution. As readers, we gain an insight into what it may have been like for the characters to have lived through those events. They have painful traumatic experiences and yet they continue to face the practical demands of life, of the necessity of continuing to exist, regardless. Time passes with no regard for the feelings of the characters. It is essential for them to push forward, to move on, which leads the reader questioning how they manage to do so. The stories clearly show that the need to survive will persist in the most challenging of times. Yet they also lead us to consider what is to be done with such history and unresolved feelings. It becomes clear through the stories that simply suppressing the memory of trauma does not resolve anything, instead allowing its impact to manifest in the present day.

An idea that I particularly appreciated in the book was of inanimate objects, such as buildings and furniture, bearing witness to the facts. In ‘Death at the Wukang Mansion’ we learn that the Wukang Mansion, in Shanghai, was built in 1924 by a Hungarian Slovak Architect who was a prisoner of war and landed in Shanghai after fleeing Siberia. This time period is described as ‘the roaring 20’s’ in

Shanghai and Wukang Mansions as ‘fabulous.’ Ironically, Ling, the protagonist, is being held against her will there during the Cultural Revolution, a time at which such foreign influence was viewed negatively. So much so that Ling risks her own safety when she quietly performs ballet to memories of Swan Lake, alone in her room. A building which once represented freedom and openness

signifies the opposite.

In ‘Reading a Table,’ Cloud’s grandfather restores antique tables, leading Cloud to become fascinated with them. He also makes new tables; the care he takes in carving them demonstrates their great importance to him. He believed that, ‘once a table was built and done it must stay. Not just for long, but for a generation, and others to come.’ Cloud was told that she should not fall asleep at the table because she will have dreams that are not hers but that are those of others who have sat at the table. In this story, the table is witness to people and events of the past and carries their impact into the present. It symbolises the desire to forget and the impossibility of forgetting.

In ‘Cooking for Madame Chiang,’ we again observe the banality of horror. Chang’er deliberately injures herself, leaving a nasty scar, to escape capture. At a time when people starved around her, Madame Chiang Kai Shek used milk to wash her face daily. Chang’er is grateful to be granted the opportunity to work for her and, rather than focusing on the injustices before her, she is enchanted

by the milk and the opportunity it may give her to beautify herself and heal her scar.

‘Back to Beijing’ is a heart-wrenching account of a woman writing to her sister repeatedly and yet never receiving a response. She is told that she is losing her mind and is in hospital, yet she refuses to give up getting in touch with her sister.

‘The Invisible Window’ introduces a group of female friends. They managed to escape the horrors of the Tiananmen Square massacre in 1989 and have been living in France for years. They have not been able to escape survivors’ guilt.

In ‘Dear Chrysanthemums,’ Mei’s father was considered to be a member of the bourgeoisie, so when she was young, she was sent down to the countryside in Anhui province. She had to give up music and take on the hard labour of picking chrysanthemums and drying them so they could eventually be sold as tea. We later see her as an elderly woman, with a vase of beautiful chrysanthemums on display next to her. We understand that chrysanthemums can represent beauty or they can represent the torture of being forced to pick them all day long.

From the collection of stories in Dear Chrysanthemums, we discover that an object does not inherently have meaning but rather gains its meaning through the context and time in which that object finds itself. Similarly, a person will have a completely different life depending on the time period and environment they are living in.

Reviewed by Catherine Shipley

Reviewed by Emma Part, 21/2/24

On the 14th February 2024, Fiona Sze-Lorrain came to Leeds to talk about her new book Dear Chrysanthemums. By this point, I was over halfway through the novel myself and really enjoying it, but after hearing her speak I found a new depth to the novel. It was much easier to identify the author’s voice within the work, and I found a lot of things she had to say resonated with me.

On the 14th February 2024, Fiona Sze-Lorrain came to Leeds to talk about her new book Dear Chrysanthemums. By this point, I was over halfway through the novel myself and really enjoying it, but after hearing her speak I found a new depth to the novel. It was much easier to identify the author’s voice within the work, and I found a lot of things she had to say resonated with me.

The structure of this novel is particularly intriguing. It is a novel told ‘in stories’, some of which were written as long as 15 years ago, Fiona revealed. When questioned why she chose this particular structure, she claimed she gets bored easily, and this posed a way to shake things up a bit. It seems as good a reason as any. And this collection is certainly not boring – the short but engaging chapters switch between time zones and time eras from chapter to chapter. I can see why the lack of chronology might be troubling for some, especially those not well versed in Chinese history, but I found this a refreshing approach to Chinese historical fiction, and it was an interesting way to see how historical events impact the future, and how recent happenings link back to the past.

Each time period takes place in a year that ends with the number 6 – a number which in Chinese divination is associated with a smooth life.

“How about six? Can a table have six legs? Or four legs and two hands?”

“No, darling. Six is a divine number. It means a smooth life, a perfect path. Nineteen sixty-six, 1976, 1986… any year ending with 6 is a round year. In Chinese divination, we mortals aren’t supposed to lead a life too perfect to be true.” (p.88)

This smoothness is reflected in the cyclical structure of the novel, whereby the last story links back to the first, and this I felt tied up loose ends nicely. Not that you receive all the answers you want from the ending of this novel – I found it ambiguous, but perhaps deliberately so, you must draw your own conclusions of what might have happened to each of the characters.

Fiona called herself the ‘champion of the understatement’, and I believe this really shines through in this work. These stories are mysterious, each with an unexpected twist that caught me by surprise each time. They seem simple, trivial stories about everyday happenings, but if you look a little deeper, you’ll notice these stories are loaded with social commentary, notes on the female experience and musings on sexuality, all touched on in a subtle, rather authentic way. In a novel that centres around the theme of erasure, the ‘white space’ between the lines, what is left unsaid or just alluded to, is where you’ll find the true story.

The ‘authentic’ feel to the novel could perhaps be a result of the blend of memoir with fiction in places of the novel. Fiona spoke on inspiration she took from real life experiences she has had, and people she has met (such as her music teacher). There is a subtle comedy to this novel that I also really enjoyed.

“Teacher, let me write about you.”

“How -- a book? Fiction or nonfiction?”

“I don’t know… Maybe a play, a film script.”

“Who’s going to play me? Michelle Yeoh or Meryl Streep?” (p.155)

Fiona compared the writing of this book to the process of writing a piece of investigative journalism, whereby she brings people together through their collective memory of a particular historical event or time period. This is a particularly interesting approach to Chinese history, as many events have been forcibly removed from public memories, and thus only exist in a private, shared memory of those who experienced it first-hand.

This theme of preserving memory is also expressed in the strong sense of place that is created throughout the novel. That’s not to say this novel takes place in one specific place – it switches between time zones to travel from France to Shanghai to New York, much like the author herself. But the in-depth descriptions bring life to places like the Wukang Mansion or a French church, and the changing eras allows us to peer into the life of this specific structure, how it is maintained and kept and used. For example, in the first story, ‘Death in Wukang Mansion’, the atmosphere of decay created by the author juxtaposes the image of grandeur the protagonist expects of the Mansion:

‘The corridors were cramped with pots and pans, piles of newspapers and chaotic columns of cardboard boxes. Singlets, blouses and pants were drying on racks and wires that zigzagged haphazardly across one another in midair. The place smelled of charcoal, leek and damp bricks. The odour of ruins jolted Ling out of her imagination, the fabulous Wukang Mansion from the roaring twenties.’ (p.6)

In this way, place and time become their own characters, and they are constantly in dialogue with one another, as a specific building might be held in revere in its later life, or abandoned, despite its once important status. No matter what purpose a specific place served, it is kept alive through its use as literary setting, and in this way the author once again prevents erasure.

Fiona also expressed an interest in objects and their ‘afterlife’, and this I found a rather romantic concept to explore. In The White Piano, the author compares the piano to a pregnant woman:

‘By then it had started to drizzle, and everyone hurried to wrap up the piano with more layers of bedding until it looked like an oversize mummy with a fat belly. In fact, Willow told herself, it seemed like a pregnant woman, blindfolded and kidnapped and hauled up in broad daylight before going into labour or worse, suffering a miscarriage.’ (p.72)

Here, the allusion to a miscarriage emphasises the precious nature of the piano, perhaps because of the importance the protagonist attaches to it. It is an interesting idea to explore – the significance we assign to inanimate objects, to their history and upkeep, and the significance they might hold in the history of our own lives. In Reading a Table, a table is also personified:

“Yeye, can we talk to tables?”

“Of course, dear. Tables have stories to tell us. Sometimes they tell us what we don’t want to hear. You must learn to read them.”

“Read stories or tables?”

“Both. Tables aren’t any different from books – they have faces. Tables are open books. They don’t need words.” (p.88)

The idea of an object’s history being a story invoked a revelation in me. Very rarely do I consider where a chair or table was made, who made it, or how many people have sat on it before me. It is interesting to consider against the backdrop of modern-day over-consumption or throwaway culture, whereby objects are created, destroyed, bought and sold with little thought of its origins, or where it might end up in the future. The grandfather in this story, who builds tables and teaches his grandchildren about their significance, was a very endearing character, and perhaps one of my favourites in the whole novel.

In these stories we meet a host of what one might call ‘unlikeable’ female characters – that’s how Fiona described them. However, I don’t know if I would call them unlikeable. I believe they are subjects of their environments, that they simply react to the conditions around them. Presenting female characters who are sincere and genuine and relatable in literature is very important to me. I feel to suggest a female character must be likeable is almost to suggest that women are not human, that they don’t have bad days or complex emotions. Watching these female characters seek each other out, betray one another, or lift one another back up was one of my favourite parts of the book.

One of the most interesting takes I took from Fiona was her insistence of finding a meaning or purpose in life, over chasing enjoyment. Of course, if you can find both that’s great, but enjoyment cannot simply be learnt, it must be earned. One of the easiest ways to do that is to experience life – talk to people, travel, learn, read, live. Enjoyment can be found in human connections. A novelist expresses a very private part of themselves through their writing, and thus literature for me is a way or learning about human experience from actual humans. It expands my capacity for empathy, as well as providing entertainment. The overwhelming feeling I felt after finishing this book is that is conveyed the human experience, especially the female experience, in a very authentic way. This unfiltered approach landed well with me.

Reviewed by Emma Part