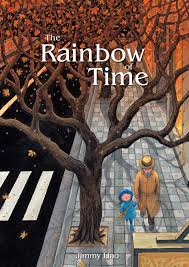

The Rainbow of Time by Jimmy Liao

translated by Wang Xinlin and Andrea Lingenfelter

Balestier Press, 2018

Publisher's Blurb

Her mother’s departure marks the beginning of a lonely young girl’s lifelong love affair with the world of film. One day, she encounters a boy. In parting they promised each other: no matter what happens in future, they will meet again in the movie theatre. Set against the timeless backdrop of classic and familiar European films, so begins a story of three generations of love, loss and faith that will thrust one girl from childhood into the heart of womanhood. As she soon discovers, real life is often far more poignant than the movies…

With full-page illustrations from one of Taiwan’s most evocative and popular illustrators, The Rainbow of Time is a stunning tribute to the power of love, faith and the redemptive magic of films.

Reading Chinese Network Reviews

Reviewed by Cynthia Anderson, 8/1/18

A beautiful graphic novel about love and loss. Jimmy Liao’s The Rainbow of Time is the story of a young girl coming to terms with a mother who has abandoned her. The novel’s gorgeous illustrations, bursting with color and emotion, enriches the reader’s experience of the story.

A beautiful graphic novel about love and loss. Jimmy Liao’s The Rainbow of Time is the story of a young girl coming to terms with a mother who has abandoned her. The novel’s gorgeous illustrations, bursting with color and emotion, enriches the reader’s experience of the story.

Seeking solace in films, the young girl’s father brings his daughter to the cinema after his wife has abandoned them. ‘Mother loved movies more than anything,’ he says, ‘Maybe some day, we will see her in the cinema.’ The illustration covers the entire two pages, on one side is a close up of a dark, hard asphalt street, on the other side the girl and her father walking on a light grey sidewalk under bare trees in an autumnal light on their way to the cinema. Film is not only an escape for the girl and her father, a way to experience indirectly the lives of other people, but it has the potential to keep the darkness away by holding onto hope. ‘I was deeply convinced that one day I would see her [Mother] again at the cinema.’

Blue is the color of hope in The Rainbow of Time. The first time we meet the girl she is dressed in blue and when she’s pictured at the cinema watching films, she and the audience are bathed in a blue light. At night in her room when she dreams, writes in her diary or replays in her mind the most memorable parts of a movie she’s watched, blue is the dominant color. Liao seems to be reminding us that when something painful occurs for which there is no explanation, hope will help us find our way. And yet hope isn’t easy to see. Perhaps that’s why blue is such an important color in this story, for like in the colors of the rainbow, blue is one of the most difficult ones to spot as it blends in with the blue of the sky. But film can give the girl hope. Film helps her dream and imagine the possibility of one day finding her mother in the cinema.

As she becomes a young woman and falls in love with a man who is also passionate about cinema, again she experiences another tragedy without a clear explanation or resolution. Liao’s image here also bleeds across two pages—the girl floats on the surface of the ocean with a blue chair sinking below her into the darkness. ‘I drifted about in a vast, ink-dark ocean while the light grew ever more distant and faint.’ But hope does return and life goes on. She bears a child and meets another man. And by the end of the story, it isn’t clear if the narrator is reunited with her mother in reality or in her dreams, but what is clear is that she has found peace with that tragic experience.

The Rainbow of Time is a book that calls out to be read over and over again, savoring the illustrations and discovering Liao’s meanings in the rainbow of colors he presents to the reader.

Reviewed by Cynthia Anderson

Reviewed by Sarah Darwin, 2/1/18

‘My mother went away when I was little.

‘My mother went away when I was little.

Whenever I cried for her, father would say

“Come on, let’s go to the movies”’

The Rainbow of Time is a both a poignant story of loss and an ode to cinema. It’s a graphic novel with a story told in beautifully detailed pictures and brief sentences which belie more heavyweight themes including bereavement and family breakdown. The subjects are sensitively handled, often obliquely, so the book is suitable for young readers who are ready to engage with such topics, and at the same time the book has enough complexity and subtlety to be of interest to older readers, and should be particularly appealing to movie buffs of any age.

The story begins in the protagonist’s childhood. The above extract comes from the opening page, and we never learn weather her mother died or simply left. Like her mother, the protagonist develops a love of cinema, and it is there that she consoles herself, finds solace, and experiences many key milestones in her own life, including her loves and losses. Later, she follows her father’s example and takes her own daughter to the cinema to help her deal with, or escape life’s sorrows. The ending is so poignant that it brings a lump to my throat every time I reach it.

The text is a fantastic example of ‘less is more’. Most pages have just one sentence, many are devoid of text, leaving the illustration to articulate what was left unsaid. On one page the lines: “Mother, I’m terrified.. // What if someday you were to sit right in front of me // and I didn’t recognise you”, and on the next a full page image of cinema stalls superimposed with a violently windswept cornfield, the protagonist alone in a sea of empty seats. Buffeted by the wind, wide-mouthed, she holds her arms tightly around herself. The line breaks are carefully considered to lend a lyricism to the text, and when the text is overlaid on the illustration, the positioning of the text complements the images. Under such constraints, It’s quite a feat of translation by Wang Xinlin and Andrea Lingenfelter to present a translation so elegant in both language and layout.

‘Less is more’ also applies to the detail of the story. As well as the ambiguity surrounding her mother’s departure, the protagonist’s husband’s mental illness seems to be implied, yet not clearly stated with a brief ‘Not long after, he fell ill [...] He had imprisoned himself in a world of darkness, and I was powerless to help him’. The brevity and indirectness prevent the story from feeling too bleak or upsetting when it deals with upsetting issues.

There are abundant references to films in the book. The attention to detail in the lighting and shadows and the compositions of scenes have a very cinematic feel. Sometimes you see a scene or element straight from a film serving as a visual metaphor in the story, such as a sinking ship for the protagonist’s floundering relationship, or King Kong providing a shoulder for a young girl to sit on. The street scenes frequently feature movie posters, and there are several scenes in which films are being shown on screen. A few of the references are easy to spot, but many of them will only be identifiable by a more avid film fan. According to the useful list of references at the back, there are references to films including Chungking Express and Les Quatre-cents Coup, and many more. I feel it would be wonderful to first read this book as a young teenager and later feel a flash of recognition if you happen to see the films later.

The form of the book also has a cinematic feel. Like a film, much of the storytelling and the emotional weight comes through the actions of the characters and subtle details in the images, there’s very little insight into any of the characters’ thought process. On one page, the protagonist’s husband, overcome by frustration and thwarted ambitions sits on a dry stone wall in an eerie landscape with the caption ‘His world had come to a grinding halt // in a desolate weeping meadow, // where bitter winds howled endlessly’. The interiors have a set-like appearance, and given the frequent film references, I wouldn’t be surprised if these were indeed borrowed from films.

The illustrations are incredibly appealing; the colours are rich and vibrant, and there’s a great range of different styles of imagery from the realistic to the fantastical, and wide range of seasons and weather conditions. Many of the pictures have interesting or perplexing details to linger over; movie posters and references, a side profile of a woman in a window who appears to be on a drip (who is she?), incongruous rabbits, the tantalising reference to “the nowhere man” in a poster to whom the book is dedicated (who is he, why is the protagonist looking at it?), a huge furry tail in an airport window. Metamorphosed images of the cinema stalls are frequently used to cleverly reflect the protagonist’s mental state.

The only significant flaw of the book, for me, is the lack of detail in the faces. Especially given the level of detail in the scenery, the faces aren’t particularly rich in character. On the first read I mistook a male character on his reappearance for another and was baffled about the protagonists reaction to him. I also find it difficult to tell whether recurring vague images are intended to be the same person, presumably the mother, or different people, perhaps characters from films I haven’t seen.

Overall, The Rainbow of Time is a pleasure to read and reread. It makes a great coffee table book for you or your guests to flick through, and when you read it through, it’s surprisingly moving.

Reviewed by Sarah Darwin

Reviewed by Zahra Raja, 30/12/17

The Rainbow of Time is a beautifully illustrated story that documents the life of a girl who loves more than anything to go to the cinema, and her transition from child to adult is set against the backdrop of the cinema that she often frequents. The beautiful illustrations depict the major events in her life and are heavily influenced by her love of seeing films; our heroine uses them as a form of escapism which gives the book a wonderful dreamlike quality, whether melancholy or comforting. The story itself is brilliant in its simplicity and is highly readable both for adults and children.

The Rainbow of Time is a beautifully illustrated story that documents the life of a girl who loves more than anything to go to the cinema, and her transition from child to adult is set against the backdrop of the cinema that she often frequents. The beautiful illustrations depict the major events in her life and are heavily influenced by her love of seeing films; our heroine uses them as a form of escapism which gives the book a wonderful dreamlike quality, whether melancholy or comforting. The story itself is brilliant in its simplicity and is highly readable both for adults and children.

Our protagonist is a young girl whose mother left when she was very young. When she felt sad, her father would take her to the cinema, each time telling her that her mother too loved the cinema, and maybe one day they would spot her there. This becomes routine for the pair and our heroine soon loves the cinema both for the films and for the possibilities it offers. She meets her childhood love in the cinema, and the illustrations detailing the ups and downs of their marriage are some of the most beautiful in the book. What I loved most about the story was the utter lack of bitterness from the girl towards life’s misfortunes, both towards her mother’s absence and other troubles; there was only her grief, and the cinema to help her get through it. Certain events and illustrations are left open to interpretation, and we’re never really sure whether our heroine finds what she’s seeking, but what remains constant throughout the story is the feeling of hopeful optimism that she holds onto.

Jimmy Liao’s vivid art propel the story to another level. The pictures he shows convey an incredible depth of emotion, whether our heroine is feeling playful, comforted, reminiscing, or grief; the text of the story is relatively simple and restricted to a few lines per page, but any more would overwhelm and distract from the illustrations; Liao manages to get the balance just right. One of my favourite illustrations is when our heroine describes her grief after her life takes a turn for a worse, and she speaks of “a ship of happiness” that has “already begun to founder over the horizon”; the corresponding picture shows a sinking ship, and the words are carefully split so they appear both above and below the water. A lot of thought and care has gone into not only the words and the pictures, but how they work together, and the translators must be commended here for managing to maintain the balance in English. Perfect for a lazy Sunday afternoon read with a cup of tea.

Reviewed by Zahra Raja

Reviewed by Barry Howard, 30/12/17

Having previously read Jimmy Liao’s “Turn Left, Turn Right” (向左走, 向右走), I was looking forward to another of this Taiwanese illustrator’s tales. Fifteen minutes later and all I could think of was how superficial the story was. Not even the pretty artwork could save it. Where the book went wrong for me can be seen in a comparison with “Turn Left, Turn Right”. That is a simple ‘boy meets girl’, will they/won’t they story; simultaneously asking us to ponder how insignificant decisions can have life-changing outcomes. The illustrations play a supporting role, filling gaps and linking scenes, allowing for a minimalistic writing approach to succeed.

Having previously read Jimmy Liao’s “Turn Left, Turn Right” (向左走, 向右走), I was looking forward to another of this Taiwanese illustrator’s tales. Fifteen minutes later and all I could think of was how superficial the story was. Not even the pretty artwork could save it. Where the book went wrong for me can be seen in a comparison with “Turn Left, Turn Right”. That is a simple ‘boy meets girl’, will they/won’t they story; simultaneously asking us to ponder how insignificant decisions can have life-changing outcomes. The illustrations play a supporting role, filling gaps and linking scenes, allowing for a minimalistic writing approach to succeed.

In contrast, “The Rainbow of Time” attempts to say so much that it ends up skimming over and trivialising important live events. We have a young child who has lost her mother, her father struggling to go on, first loves, marriage, the fallout of failure to achieve a dream, ageing, and loneliness. Perhaps the book can be appreciated if you happen to have seen the eclectic mix of 20+ films it acknowledges. Quite an ask, with the result that this is possibly a book that means a lot to the author but will be lost on many a reader. A bit like how certain sounds/songs or smells can represent people, places or events particular to our own lives. What fails to register with one person, can conjure up profound memories for another.

Reviewed by Barry Howard

Reviewed by Cuilin Sang, 26/12/17

As an old-fashioned reader of words, I have to admit that at the first reading of the Taiwanese author-illustrator Jimmy Liao’s The Rainbow of Time, I wasn’t sure if I could put my finger on it. I was later greatly enlightened by my fellow reviewers when we met in November 2017 in Leeds. I began to realize that the key to engage with this book might lie not in “reading,” but more in “viewing.” As Sarah Tindal Kareem puts it in her review of Peter Mendelsund’s What We See When We Read, “reading is a kind of seeing, an activity in which we respond as much to visual cues as to linguistic meaning.” It is especially so when we “see” or “view” a work like The Rainbow of Time, a multi-media book where words are complimentary to colors, pictures, and perhaps most importantly, movies.

As an old-fashioned reader of words, I have to admit that at the first reading of the Taiwanese author-illustrator Jimmy Liao’s The Rainbow of Time, I wasn’t sure if I could put my finger on it. I was later greatly enlightened by my fellow reviewers when we met in November 2017 in Leeds. I began to realize that the key to engage with this book might lie not in “reading,” but more in “viewing.” As Sarah Tindal Kareem puts it in her review of Peter Mendelsund’s What We See When We Read, “reading is a kind of seeing, an activity in which we respond as much to visual cues as to linguistic meaning.” It is especially so when we “see” or “view” a work like The Rainbow of Time, a multi-media book where words are complimentary to colors, pictures, and perhaps most importantly, movies.

A mini female bildungsroman if judged from the word count, this picture book nonetheless has a capacity for renewable and abundant information. Except for a few pages, the color tone of the book is extravagantly warm, counteracting the sub-themes of loneliness, sense of loss, and sadness throughout the text. The overarching theme seems to be the passion for movies, mingled with the sweet-bitter realization and acceptance of the sacrifices involved. The narrative gaps between the terse words are filled with pictorial page spaces, where the protagonist’s life syncopates with tides of passion associated with movies. Each page transforms into an independent yet also interactive visual unit, connecting the narrative flux with a grammar predicated on eyes.

The interesting thing about “viewing” a picture book is that the viewer/reader gains a particularly stronger sense of him/herself as part of the audience, a communicative role often ignored by the reader of a book comprised entirely of words during the reading process. The fact that movies feature predominantly in this book further strengthens this sense and complicates the viewing experience. Conscious of the viewing act due to the ostensible visual qualities of the book per se, the viewer/reader is also invited to participate in the viewing and decoding of the movies alluded to in the book. Various familiar movie scenes are depicted as direct emotional and psychological responses from the protagonist, whose greatest joy is to live the lives of different characters in the movies through her imagination. Viewing is thus inextricably multi-layered, and the viewer/reader becomes increasingly intertwined with the things being viewed through the bond formed by the recognition of the movies and the identification with the protagonist.

In this pictorial text about life with movies, the flow of time, like the circulation of meaning in a movie, can hinge on visual intertextuality. As one element that evades the restrictions of mise-en-scene in movies, time works more freely on the elastic psychological landscape of the viewer. Taking advantage of the flexibility and the immediacy of time in visual media, Jimmy Liao constructs a cylinder of time that rotates with the paginated tableaux vivants. From the real time of the viewer/reader, to the decades of time experienced by the protagonist, and to the condensed time in the movie scenes, time in this book is multi-contextualized and visually concretized. Words can help the viewer/reader get oriented to the temporal contexts, but the sense of temporal change is materialized through the visual symbols. Time moves with a variegated rhythm adaptive to different contexts and assumes corresponding textuality in each of them. It becomes the form and the content of the book, underlying the symmetry of life of the protagonist. Like her father, the protagonist experiences the loss of a loved one to the unstoppable passion for the movies. Also like her father, she does not let this diminish her own passion for watching movies. She lets time happen and reconcile the matter in a “timely” fashion. Patience, in these serenely rendered pictures, is almost synonymous with love, which preconditions and sustains the arduous life involved with the movies.

The alternation between the patient and the passionate time of the protagonist seeps into the real time of the viewer/reader, reformed and recontented. In this alchemic interlacing of time, a sense of wholeness is achieved and played on loop. Jimmy Liao’s readers, most of whom are actually adults instead of children, are more often than not contented, despite of the darkness and imperfection of life exposed by the artist. In this case, it is the nearly perfect symmetry in life germane to the textualized and intertextualized time that gives his readers satisfaction and allows them to smile with tears and to cry with hope.

Reviewed by Cuilin Sang

Reviewed by Tamara McCombe, 17/12/17

If I say The Rainbow of Time is an adult graphic novel don't think I am talking about a comic book. Jimmy Liao's book is a clever combination of poetry like prose and images forming one of the most enjoyable books I have read this year. As Walt Disney productions used to say, 'there is something for all the family'.

If I say The Rainbow of Time is an adult graphic novel don't think I am talking about a comic book. Jimmy Liao's book is a clever combination of poetry like prose and images forming one of the most enjoyable books I have read this year. As Walt Disney productions used to say, 'there is something for all the family'.

Does the text supplement the image or vice versa? Both. Take one away from the other and you would lose the harmonious balance that forms Liao’s novel. Where the text is placed within the image has been meticulously judged and plays as much a part of the image as the strokes of colour. The translator of this book, Andrea Lingenfelter was an excellent choice. She is a poet herself and translator of much poetry from the Chinese mainland and diaspora. Her poetic sensibility is evident in verses such as “Often, we would wander/ aimlessly from place to place/ drifting and drifting, all the way to the cinema”, the enjambement portraying the young protagonist’s sense of loss, yearning and lack of direction. Every double page picture-verse composition warrants lingering over as each contains numerous levels of questions and meanings if you take the time to explore them - I suggest you do. Movie-loving adults will enjoy spotting the real movie posters dotting the background scenes and all ages will be drawn to the detailed and kaleidoscopic colours, so vivid you yearn to touch them. So vivid are Liao’s images some of his creations they have unsurprisingly been the source of theatre adaptation and more recently developed into virtual/mixed experiences that have toured the world.

Before turning his Taiwan Chinese Culture University trained hands to literature and film Liao worked in an advertising company, little wonder Liao’s pictures are so arresting and appealing. The author-illustrator’s skill is how he manages to fit so many tropes and references into every picture yet make them feel so full of space. One picture of the child protagonist riding a lion at once reminds the audience of C.S. Lewis’ classic Aslan character in the Narnia series, yet the Gremlin-like green cat could be out of the Hollywood film or Lewis Carol’s ‘Alice in Wonderland’, and the dark woods engulfing the two from Maurice Sendak’s ‘Where the Wild Things Are’. If you read this book with a child you can engage them by hunting for the repeating balloon and cat figures. Or, if you are reading as a solo adult, enjoy losing yourself in the deep imagery, and pondering why light shines from the protagonist’s eyes or whether the character at the end is real or imaginative. I wonder why though Liao chose all his characters to be Caucasian and not his native Taiwanese.

Do not be mistaken in assuming this is a jolly picture book. There are dark, searching emotional questions about coming to terms with the past and moving on. Is the protagonist weak for losing herself in films in order to avoid the reality of departed loved ones? Or is any mechanism for overcoming grief acceptable if it aids recovery?

The author's note at the beginning of the novel mentions the work is a homage to cinema, with each image reminiscent of a movie still Liao does a great job in this respect. And as easily as watching your favourite movie, this is a text I look forward to rereading and taking away something new each time I pick it up.

Reviewed by Tamara McCombe

Reviewed by Henry Yunwei Wang, 14/12/17

At the age of 29, she encountered him, another cinéaste in the cinema. He talked many things about the movies he wished to direct; She corresponded many things about the movies she wanted to watch. He proposed, and she said yes. He then made a movie, failed, compliant, fell ill and left in silence. Just like her mother's departure when she was little.

At the age of 29, she encountered him, another cinéaste in the cinema. He talked many things about the movies he wished to direct; She corresponded many things about the movies she wanted to watch. He proposed, and she said yes. He then made a movie, failed, compliant, fell ill and left in silence. Just like her mother's departure when she was little.

Back to the very beginning. "Come, let's go to the movies." "Mother loved movies more than anything." "Maybe some day, we will see her in the cinema." Father's words brought her all life into the cinema.

At the end of one movie, his father began to weep. She asked why, and father answered, "...It's just that the ending is so beautiful."

At the end of the story, she rested her head on an elder lady who had her mother's fragrance smell. After the movie, she heard a gentle voice, "Miss, is everything alright?". She wiped tears and gazed her face, smiled, "I'm fine. It's just that the ending is so beautiful."

You may easily watch a movie again, or listen to a song again, anytime. However, it could be extremely difficult to find that person who accompanied you on that day. So you may then google "How to forget...". It comes out the most sentence been globally searched, "How to forget someone." But when you stop by "How to f...o...r..g...", it soon comes out in the second choice, "How to forgive yourself."

We are all playing our own life role, when reading stories about others.

Each stage of the heroine's life is given extra resonance by the films she chose to escape into, and which then reflected back to the reality. The melancholic atmosphere reads never depressed by Jimmy Liao's brilliant application of colour contrast and Andrea Lingenfelter's warm translation, reminders of an unavoidable life lost but also an optimistic future that awaits.

Jimmy paints illustrations, the girl watches movies, and I write poetry. When my parents were working abroad for the family in my childhood, I was raised up by grandparents and taught how to fill in the lyrics of Ci. I lost one beloved grandpa at 10, and heartbrokenly another at 22. I still write one or two poems per year, telling them what happened, for me just like a telephone could only be dialled once a year to the heaven. It is the Rainbow of Time that recalls all these feeling. So I would like to dedicate my private memories to Jimmy and readers who were touched by it.

"恰似花间回首肠断处。秋风慢,冷月无霜。天高云淡,水清静流;羌管空城,落叶新愁", "望瑷靆云蔼染寒烟,渚汀霜淡。梲移舟远,鸿雁声断。梦倚沁露柔肠,催把斜阳觅", "疏云晴霄,烟柳擎起,朱阁琉璃华影。缓露晨霜,琴籁空彻,引萃泠花无数。只是撷叶光阴", "莲蓬苦芯若去,竟似藕间壑,空是离人恨语" (at 18 yrs old)

金缕曲 题昆曲《西厢记》 2011

偏将韶华怨。竟须将,心境幽颤,孤鸣相伴。十三弦横玉惊鸾,依约响彻天未。寻他与,画角长短。若问生涯原非梦,凭心事,拟鲸波云壁。半西风,相思雨。

此情若有双鱼寄,也知她,飘絮冷暖,凝眸曾记。惜教终宵成转侧,怎敌换宫移羽。惊密语,酽茶喫去。芳樽惜有粉词倚,也笑我,未沾言人醉。只莫恰,觉来意。

自和韵 金缕曲 木兰三慢 2012

闻筝心欲碎。声催忆,红笺锦字,浮萍窗曲。只花归琉璃剩碧,暗念陨星如箭。再铿锵,一人而已。莫会泠风独自凉,来年非,马齿又长矣。君怎见,孤鸾泪。

自斟龙井忍重理。休管甚,初雪未融,冷暖难济。恐他提流年似水,都教暗处销魂。寻思起,从头不悔。一日相期千劫在,似旧曾,比翼蓝桥去。缘聚散,愿如水。

减字金缕曲 子夜罪己 2013

是梦久应醒。傍时缘,草本木末,胡儿铿义。语宾鸿文园憔悴,筹诉苍玉离觥。云中庭,长须一饮。急公怎会松竹意。钗分钿,终为一利所驱。宁怀石,解瑶席。

此生唯有麟阁材。狂生耳,夷结凶险,肃毅骑鲸。灞陵夜中人所戏,羞尽铁帽福荫。虎落堪击。提猛赋文星探斗。扫些个,那情侬诈虞。高勒马,天心齐。

金缕曲 西城决绝词 2014

木稍渐落矣。偶然间,斜阳蒿草,苍梧旧景。每寻会三荫松语,却换他人颤倚。恐重逢,疏称而已。独坐滴阶听夜雨。对月饮,泪晓平生句。清可若,一杯水。

文才难教留粉本。向樽前,风裳水珮,别离时节。廿载人情颇亲历,总非生死相许。暗销魂,荔墙芳寒。私盼早生非明慧,曳素衣,无至情可也。观顿首,尽哽咽。

金缕曲 密札重启为记 2015

垂成一着倾。动梁尘,平芜远树,云涛无际。锦素沉沉两未期,鱼雁空相传误。恐须臾,砉然一叹。而今百念均天梦,时与命,不忍任天付。看传神,心如铁。

横波秋寸相思错,料当初,黛颦微扫,风流酝藉。谁知我非池中物,咫尺蛟龙腾雨。生四角,骅骝长啸。斜阳偏与黄昏近,转遮面,睽阻潸然泪。重拍栏,补天裂。

金缕曲 旅英遥祝亲友为寄 2016

年少已逡巡。旧年非,生鱼包裹,半来中许。从前谙尽江湖味,陡顿人情冷暖。鄙俗尘,遂成知己。地皮卷尽犹飞肉,长门事,到骨槐安梦幻。深埋轮,分胡越。

白玉楼成方不悔。穷胜游,功名破甄,生涯蜡屐。醉拥诗兵驱笔阵,抱瓮水流急景。读书事,瓜甜蒂苦。唯念家宴除夕夜,待蝉鸣,把安期枣献。然诺重,谨再拜。

金缕曲 炎凉浮生夜作歌 2016

转首成乖各。萦回雪,明蟾冷淡,藏冰北陆。哺慈乌天夺祖去,长啸梁尘暗落。只往昔,最难持忆。早许留步晚成仙,骖鸾鹤,种玉菖蒲九节。看锄云,泣不尽。

泛湖海人世舆台。待松凋,伤弓塞雁,三生犹历。隐番邦白凤思凡,班荆蛾黛倾欹。恐薄媚,痛地割剖。清歌把袂月人稀,谁能过,晓情关痴毒。磨灭后,皆勘破。

金缕曲 见玦醉书随寄 2017

况是伤心绪。偏食月,霭阴云覆,滂沱急雨。少年养成心远性,怎肯名牵利役。住灌江,未曾左计。骊驹临流痴不渡,惜障泥,坎止流行随遇。心字篆,神仙曲。

奈何将菱花扑碎。曳单影,金堂玉马,茅舍竹篱。承堪知五城三国,挨却昔匣还玦。唯胸次,冰雪一瓯。恨疏狂不早思量,成睽阻,才读临邛赋。凭谁诉,厌厌地。

金缕曲 丁酉中秋家书夜雨 2017

叩问竹安否。淅初潇,商飙乍发,碎影穿帘。料芳悰厌浥沧苔,还照吴门递迢。欲盈掬,霜天晓角。露囊锥小试何难,郑公风,亲挽掀髯一笑。银挂蜡,心字烧。

转轮云镬汤清凉。平生壑,深蛰惊雷,天听硬语。三代素襟孤酽,柏台金銮视草。西州路,祖训尤闻。领凤衔民歌归诏,须直笔,奈肯雪轻飘。滞东风,缓拍调。

Reviewed by Henry Yunwei Wang

Reviewed by Michelle Deeter, 12/12/17

The Rainbow of Time starts with a heart-breaking line: “Mother went away when I was very little.” Should I keep reading, or should I grab a box of tissues? I decide to continue. The statement is straightforward, showing that the young girl who says it has accepted this fact even if she does not fully understand it. Every time she questions her father, he says that maybe they might run into Mother at the cinema, and they go watch a film together. Watching films becomes the girl’s favourite pastime, and she watches films when she feels happy and sad. She goes to the cinema with family and friends and on her own.

The Rainbow of Time starts with a heart-breaking line: “Mother went away when I was very little.” Should I keep reading, or should I grab a box of tissues? I decide to continue. The statement is straightforward, showing that the young girl who says it has accepted this fact even if she does not fully understand it. Every time she questions her father, he says that maybe they might run into Mother at the cinema, and they go watch a film together. Watching films becomes the girl’s favourite pastime, and she watches films when she feels happy and sad. She goes to the cinema with family and friends and on her own.

The girl grows up and falls in love with someone who loves the cinema as much as she does. She enjoys discussing films with her husband and soon enough, she gives birth to a baby girl. When she encounters problems in her marriage, she does not blame anyone, but continues going to the cinema as she always did. Years later, she is rewarded for her patience and her steadfast love.

Employing simple and clear language, this book is a gem that can be enjoyed by readers of any age. The delightful illustrations sparked my imagination. Although the book touches on heavy themes like abandonment and anxiety, the story is a hopeful one, brimming with love. My favourite part of the book is the determination of the main character. She shows an unwavering loyalty to her family and she is determined to live a happy life, even after encountering challenges that would make most people want to give up. She refuses to succumb to disappointment and notices beauty in all things, especially in films. When she feels confused, she “stumbles upon answers” in films. Film is the reassuring companion in the protagonist’s life. There is no antagonist in The Rainbow of Time, but that only makes the story more wonderful.

Wang Xinling and Andrea Lingenfelter translated the story with skill. The translation reads smoothly, allowing the story to play out without any interference. A balanced and crystal clear translation is crucial here—without it, the main character could seem submissive and weak. Fortunately, they craft their words with care. I would highly recommend this combination of a beautiful portrayal of a woman’s life and an unabashed love letter to cinema.

Reviewed by Michelle Deeter

Reviewed by Andy Thomas, 13/11/17

This cinematic book works for me on several levels – there is both a short text and a kaleidoscope of bright filmic images in sequence but not in animation. It is deceptively simple in appearance but slowly reveals its complexity.

This cinematic book works for me on several levels – there is both a short text and a kaleidoscope of bright filmic images in sequence but not in animation. It is deceptively simple in appearance but slowly reveals its complexity.

The written text, ably translated by Wang Xinlin and Andrea Lingenfelter, tells the sad and sweet story of a woman and her relationships in forwards and reflective time. They use both the words “film” and “movie” and the words here are not quite interchangeable. But this book is far, far more than the written text. Set in and around a cinema, we see above the text a second track of images, some inspired by films, some incorporating film posters, some demonstrating primary colours and washed-out images, and some showing directors’ beaming faces in Orwellian wall mounts. And then there’s Truffaut’s hat.

In my journey I found many and different visual references, to many films which were given credit and acknowledgement for copyright reasons, to other films I and my family have seen, and to iconic paintings and images. Truffaut’s “Les Quatre Cent Coups” illuminated a blue cinema; I saw “The Snowman,”, “The Piano”, and Winnie-the-Pooh; Aslan, Rodin and Munch, and the Yellow Brick Road crossed the set; and I might have seen Versailles, Abbey Lane on the cover, “Breakfast at Tiffany’s” and the “Fiddler on the Roof”. There is a poster for “Todo Sobro Mi Madre”. Those who grew up with Taiwanese film might have seen more; there are direct poster references to “Three Times”, for example, and possibly “That Day on the Beach” and “Taipei Story”. And was that the end scene of “Grease” or “Chitty Chitty Bang Bang”?

So this is not a comic book or Manga as defined by convention, but a cinematic book where two lines of text, one visual, one written, intersect each other at written bridges offered by the author. It’s not just a reflection of text and image on each page, but an intersection of lines of meaning over time.

Readers will find that there is a vector travelling out of the book, at right angles to it, a third dimension of meaning to these two lines of texts, these two flat screens sitting together. This new vector is to be discovered by each reader individually as the product of the visual and the written expressions taken together, and it is in this third dimension that Jimmy Liao’s creative genius lies. As a writer and producer he can only point you to the vector; it is for you to discover it.

But I would not produce “the film of the book”. I felt as if I were on-line in a complex, ever changing video game, where I engaged with the two dimensions on the screen simultaneously, but travelled in a third. It is in this third dimension, where the colours of the “Rainbow” of the title meet the “Time” in the temporal sequence of the story, where I have started to travel. I can’t put the book down.

Reviewed by Andy Thomas

Reviewed by Paul Woods, 5/11/17

The Rainbow of Time is a very brief account of a person’s life, beginning when she is a little girl whose mother has left home, and continuing through her marriage, separation, having a daughter, and meeting up with her mother towards the end of the story. From very early in her life going to the cinema and seeing films are very important to the girl; she goes with her father and films help her make sense of life in the aftermath of her mother’s departure. Almost every significant episode in her life takes place in the cinema. She meets and says goodbye to her first love there, and seeks meaning as a young adult after graduation. She meets her husband there, a man who is very interested in film, who becomes a filmmaker. Her engagement and marriage also take place inside the cinema.

The Rainbow of Time is a very brief account of a person’s life, beginning when she is a little girl whose mother has left home, and continuing through her marriage, separation, having a daughter, and meeting up with her mother towards the end of the story. From very early in her life going to the cinema and seeing films are very important to the girl; she goes with her father and films help her make sense of life in the aftermath of her mother’s departure. Almost every significant episode in her life takes place in the cinema. She meets and says goodbye to her first love there, and seeks meaning as a young adult after graduation. She meets her husband there, a man who is very interested in film, who becomes a filmmaker. Her engagement and marriage also take place inside the cinema.

Ironically, the only significant part of her life which is not intimately connected with the cinema building is the failure of her marriage. Her husband grows away from her and his life becomes a film which engulfs him. She can only watch his personal difficulties with no way of participating in his life. After he leaves her, at the cinema, she faces life alone, and discovers she is pregnant. The woman at the heart of the story went to the cinema as a little girl with her father when she missed her mother, and a generation further on she takes her own daughter to the cinema when she misses her father.

At the end of the story the woman goes to the cinema with her now elderly father, and is convinced that she will meet her mother there. She notices a scent familiar to her since her childhood from a scarf which her mother had left behind. Interestingly, in a book devoted to an audio-visual medium, the woman is connected to her absent mother through her sense of smell.

To do justice to this remarkable and moving short story, it is necessary to mention the illustrations on each page of what is a picture book. The story is told as much by the beautifully detailed pictures on the pages as much as by the short and well-expressed English translation.

The pictures bring many of the principal character’s feelings and thoughts into the cinema. Spring trees, cherubs, themes from films, her sense of devastation when her first boyfriend has to leave, loneliness, fear of not recognising her mother, emotional clouds hanging over her, mists of forlornness, wintry snows of sadness, spring flowers of joy; all of this imagery appears over the rows of seats. Almost in opposition to this artistic licence, the realistic looking pictures in stills or from posters advertising films such as Trois Couleurs: Bleu, In the Mood for Love, The Wedding Banquet, and Three Times ground the story in reality.

The scenes of the father taking the little girl to the cinema and the grown woman taking her father decades later are almost identical, except that the first looks like Autumn while the second feels like Spring, possibly anticipating new life when she sees her mother.

Although the book’s format might suggest a children’s story, it contains deep themes and reflections on life. Jimmy Liao has written other books with a slightly philosophical or reflective bent, such as Pourquoi, and is comfortable exploring life’s deeper questions using a rather child-like format.

The illustrations on each page feel culturally neutral, and the features and hair colours suggest western rather than Chinese people. However, the film posters and stills are mostly from films by Hong Kong and Taiwan directors. In addition, the principal character mentions typhoons and her daughter’s name is Shin, meaning heart; there is an underlying Chinese feel. Do such cultural hybridity and juxtaposition convey the universality of human experience?

The simple account of the woman’s life and the excellent illustrations take the reader on an emotional journey with her, feeling her joys and sorrows, and the redemption when she meets her mother. The picture book format means that a lot about the woman’s life is not revealed to us, and we do not know what happens after she meets her mother. Does the relationship continue? What happens between the woman’s parents? The woman’s husband did return, but did he remain part of the lives of his wife and daughter or leave again? After the woman meets her mother the next page shows a grey, rear view of a couple with a child. The hats worn by the man and the girl suggest a flashback to the time before her mother left. After the acknowledgements comes a picture of an elderly lady sitting alone in a café; is this is the woman’s mother along again? What role does cinema play in the renewed and possibly restored life of the family?

The translation reads very smoothly, yet I wonder why the daughter’s name is transliterated as Shin. Is this part of the general hybridity in the book, and perhaps because xin or hsin might prove unnecessarily complex for English-speaking readers? Finally, I do not really like the title of the English version of the book. The Chinese title is 時光電影院, literally Cinema of Time, and cinema is a central theme of the book, which unfortunately is not reflected in the English title.

Reviewed by Paul Woods