Talking Translation: Shelly Bryant

Our special guest translator this month is Shelly Bryant, who is also a poet, author and researcher. Splitting her time between Shanghai and Singapore, Shelly has a very full schedule (as you can see below!), so we're delighted that she's been able to take the time to answer our questions.

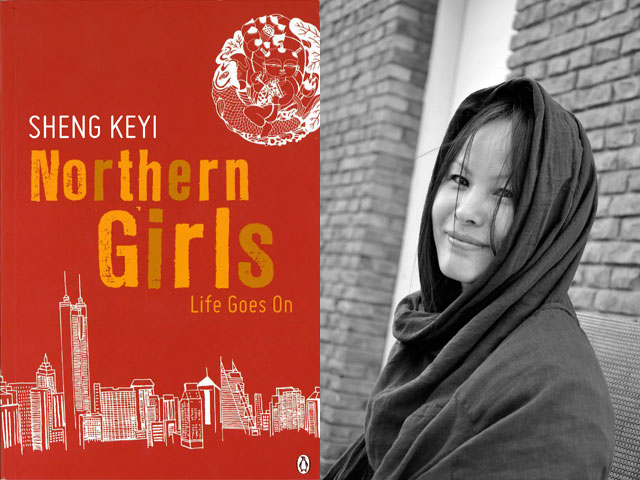

Shelly’s translation of Sheng Keyi’s Northern Girls was long-listed for the Man Asian Literary Prize in 2012, and her translation of You Jin’s In Time, Out of Place was shortlisted for the Singapore Literature Prize in 2016. Her first collection of short stories, Launchpad, has recently been published by Epigram Books. You can find out more about her on her own website here, and on our Bookclub page, where there's more about her translations of Sheng Keyi - our author of the month this November.

You've translated several of Sheng Keyi's works, including Northern Girls – what first drew you to her work, and is there a certain aspect of the translation that you've found particularly satisfying (or challenging)?

I was first drawn to Sheng Keyi’s work because it was what was Penguin China hired me to translate. I had not read the novel until they contacted me about it, but I did like Northern Girls immediately upon reading it, particularly the characters Qian Xiaohong and Li Sijiang. I think Sheng Keyi and I are a good fit as a writer-translator pair. I love her use of language and her sassiness, and am particularly drawn to the challenge of translating her sly humour. In my experience, humour is the hardest thing to translate well, and Sheng Keyi’s is particularly so because it is so fast-paced and often very subtle. This, for me, is both most challenging and most satisfying about translating Sheng Keyi’s work. It can, though, also be the most frustrating. (But then, perhaps it is the frustration that makes the satisfaction possible.)

How did you get into literary translation?

How did you get into literary translation?

My first translations were not meant to be shared, but were exercises for me to improve my Chinese. I have never had extended formal Chinese lessons, but learned mostly by ear and through the help of friends. One particular friend introduced me to poetry and essays she liked reading, and I took it upon myself to translate some of those merely in an attempt to improve my language skills and to become more familiar with the works. (I think it is probably something any writer naturally does when learning a language.) I shared my translations with various friends as a way of getting feedback and continuing to improve. One of those friends later attended an event with me at the Bookworm Literary Festival in Suzhou, where Mike Tsang of Penguin China was speaking. This friend told Mike I was a translator and prodded me to send him some of the translations I was working on. Mike kindly asked me to send something to him, and when I did, he called me up and asked me if I would be willing to do a sample translation for him. A few months after that, he offered me a contract to translate Northern Girls.

How do you choose your authors and projects? (Or do they choose you?)

Mostly I only translate what comes to me from a publisher. There are several reasons for this, one of the key ones being a lack of understanding of copyright ownership on the part of some authors, which can easily lead to misunderstandings between author and translator. I do, however, occasionally translate pieces that jump out at me as being something I just want to translate, though I do not do so specifically with an eye toward publishing them (though some have made it into print). The things I choose for myself are often associated with classical Chinese gardens, one of my key areas of interest and research, and I have translated numerous poems related to gardens, as well as some garden chronicles and other similar texts. But for work that I am translating specifically for the purpose of publishing, I prefer to have a contract in place with a publisher before commencing the work, so that there will be no misunderstandings between me and the author I am translating, or at least so that misunderstandings can be mediated through the publisher according to the terms of the contract. For the most part, this policy has served me quite well, and has mostly prevented any unpleasant disagreements between translator and writer.

You're also a poet – has your own writing influenced your translation (or vice-versa)?

I think my work as a poet has taught me a real economy with words. I tend to write short verse (including a good deal of haiku), which requires a lot of discipline and an eye for saying a lot in few words. I think my early interest in short form poetry and the economy of words it aspires to was partly influenced by my interest in traditional East Asian poetic forms. In that sense, I think there is something of a virtuous cycle in my work as a poet and translator.

I think my commitment to packing as much as I can into as few words as possible is a good fit for translating from Chinese. Classical Chinese is a perfect example of saying more with less, and Chinese humour even in contemporary fiction really utilises this approach. Chinese idioms, too, are essentially about condensing a good deal of meaning into just a few words.

Can you tell us a bit about what you're working on at the moment?

I am currently working on a number of things – I usually have several projects going on at the same time, preferably each at a different stage of translation/editing. I have completed the translation of my third full-length Sheng Keyi novel, entitled Savage Life, and it is currently in the editing stage. At the same time, I am wrapping up translation of a second book by Li Xinfeng about Zheng He in Africa, and am about to start translating a 3-volume ideological history of the Communist Party of China. I have several other shorter projects that are in various stages of development as well. One of the more exciting things I am involved in kicking off at the moment is the Singapore Apprenticeship in Literary Translation (SALT), run by my company Tender Leaves Translation in cooperation with The Select Centre and sponsored by the National Arts Council in Singapore. We have an intake of 10 apprentices in this inaugural year – all either writers transitioning into translation or professional translators learning to do literary translation – who will each work with a mentor to complete a package aimed at marketing a work in translation. We hope this will expand the pool of qualified literary translators in Singapore, working both in Chinese to English and English to Chinese translation.

Finally, we’ve been publishing a series of blog posts about reviewing fiction, alongside the launch of our Reading Chinese Book Review Network. For you, what makes a good review of translated fiction?

One of the best reviews of translated fiction that comes to mind is Nicholas Jose’s review of Sheng Keyi’s Death Fugue. Jose is extremely well-versed in the situation in and literature of contemporary China, and he brings this to bear on his understanding of the novel. It is an insightful piece that not only offers a fair analysis of the work for the reader who has yet to encounter the novel, but also brings an added layer of insight for a reader who is already familiar with it. I think a good review makes us continue to engage with the text well beyond the time it takes to read the novel and the review. It is a real gift to be able to offer such insight, and I am very grateful to those who do it so well.

Thank you for taking the time to answer our questions, Shelly!

Thank you for allowing me to be a part of your series.