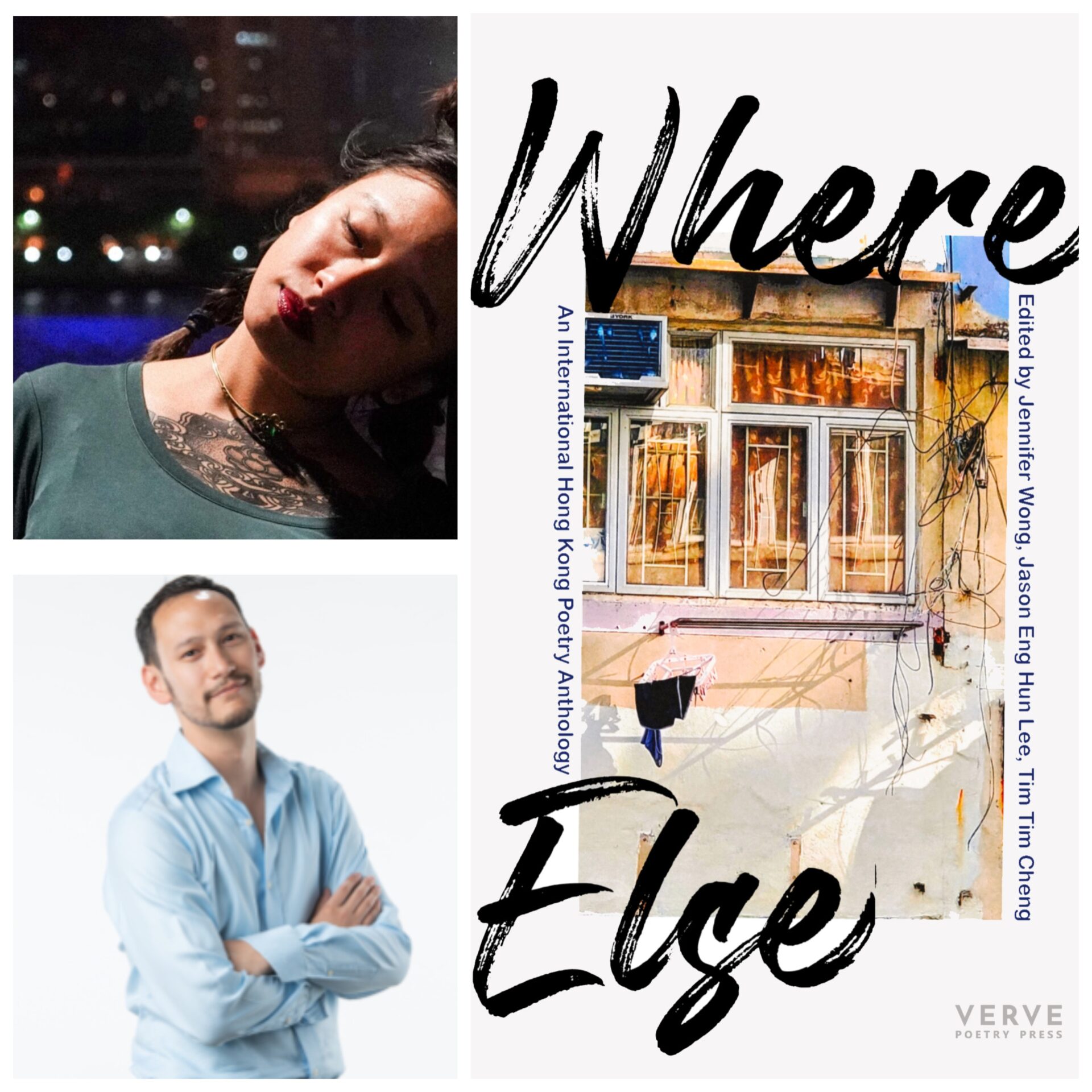

Where Else: An International Hong Kong Poetry Anthology: Editors Interview

A Companion to Where Else, Hong Kong Literature’s newest addition; interviews with co-editors

By Ms Elizabeth E. Chung, Department of English, The Chinese University of Hong Kong

This blog post serves to complement the series of interviews published by Writing Chinese: A Journal of Contemporary Sinophone Literature, in December 2023, in which I discussed the writing and artwork from a number of the Where Else: An International Hong Kong Poetry Anthology contributors. In order to get an overview of the anthology and the process of its creation, I also interviewed two of the anthology’s co-editors, Jason Eng Hun Lee and Tim Tim Cheng, to get a deeper understanding of their perspectives and project aims.

Interview 1: Jason Eng Hun Lee

Interview 1: Jason Eng Hun Lee

Following his undergraduate and master’s studies at the University of Leeds, Dr Jason Eng Hun Lee completed his PhD at the University of Hong Kong and is now a Senior Lecturer at Hong Kong Baptist University. A scholar, critic, and creative with interests from Shakespeare to Hong Kong poetry, he is of British and Malaysian-Chinese heritage – all of which he draws on as a poet and chief curator for OutLoud HK 隨言香港 [cheui4 yin4 heung1 gong2], Hong Kong’s longest running poetry collective. His poetry can be found in many places, including his 2019 collection Beds in the East.

Elizabeth E. Chung: Can you firstly tell us about the conception of this anthology? How do you go about organising and choosing the poems?

Jason Eng Hun Lee: We arrived at this idea of doing something that celebrated the diaspora, and connected them with local poets, particularly the younger generation because we wanted to give them the opportunity to share space with the more celebrated poets in the UK, the US, and elsewhere.

In composing the anthology, we were initially unsure of how many poems we would be able to fit in. We worked on the basis of having about sixty. So, I first compiled the anthology with around sixty poems separated into seven sections. It was just a case of shuffling all the pages around and eventually putting it into some kind of order.

We didn't give each section any particular description or title because it was very difficult to capture in a single word what each section was about. We decided instead to create a placeholder for each section with a quote from a poem. It's the quote, really, that is the title of the section, even if we haven't indicated it as such. There was a very specific idea, at least on my part, of starting with this idea of diaspora, of looking at Hong Kong from a distance and then going closer by talking about the history of migration, the geography of place, some of the conflicts – external and internal, talking about issues like language and identity, and then finally drawing back out with this idea of leaving or loss. We wanted to connect the diasporic element with the local element, but we didn't want them to be too separate. We were very clear, early on, that we wanted to have them side by side, so in most but not all cases, a poem coming from outside Hong Kong is paired with a poem from within Hong Kong so that you can see the different angles of approach. Some of the poems were chosen deliberately so that they could complement other poems. Also, as editors, we didn't want to have too many ferry poems, too many poems about the Peak, the tram, or the MTR [“Mass Transit Railway”, Hong Kong’s metro system]. We tried to maintain balance in terms of the content and, later on, when we were expanding the number of poems, we also thought about style and aesthetic.

EEC: You’ve had an interest in Hong Kong Literature in English since your PhD, if not earlier, and it’s the title of one of the key courses you teach as a university lecturer. How did you come to the field?

JEHL: My interest in Hong Kong literature came about during my MA program at Leeds, under two postcolonial heavyweights, John McLeod and Graham Huggan – that's how I first came into this field of ‘Hong Kong Anglophone Literature’. It was interesting because it was an extension on previous work I’d done on Anglophone Malaysian literature with another professor at Leeds, Ananya Kabir. I wanted to extend the field and talk about a place that I was thinking about moving to. Of course, both places have a very interesting relationship with the former colonial power. This idea of how we should try to represent a new aesthetic that we might call ‘Anglophone Hong Kong Literature’ is fascinating to me. When I first started my postgraduate studies at HKU, the PhD was on cosmopolitanism in Hong Kong Literature, but that didn't quite work out as intended and I ended up with a PhD on contemporary British and American fictions of globalization. It was only really in the past couple of years, with my becoming more involved in the community work of writing Hong Kong poetry, that I thought I could teach a course on this, and I could begin to try and find a marriage between what I'm researching, what I'm doing creatively, and what I'm teaching.

EEC: Talking about discovering new aesthetics in terms of Malaysian and Hong Kong Literature, your roots in the field, finding new aesthetics and being formed by it, but still being separate from these roots – did you discover anything new with the anthology, for example, in the content, people, or styles?

JEHL: Lots of discoveries. I think the most gratifying thing for Jenny, Tim Tim, and I is that we were receiving submissions from people we didn't know, who were not on our radar, particularly some newer writers coming in from Europe. That was good to see. We did have a rough prediction that we would get a lot of poems coming in from our familiar poetry networks in Hong Kong, and a lot from the UK, US, Canada, Australia, New Zealand. More or less, it turned out to be so, but we also received a lot of poems from elsewhere, which is always good. That was the first key discovery.

We were so impressed by the sheer panoply of different styles now that is available to Hong Kong poetry. We tended where possible to try and accept just one poem from each poet. The overriding thing was something that we felt could be representative of a wider Hong Kong aesthetic. There were a couple of poems that the editors really fought over to say yes or no to, and obviously there were other poems that we all thought, ‘Wow, this is great, we've got to have it.’ It's a very subjective, fallible thing, but eventually we had to look after the anthology as a whole, where the sum of all of its parts has to be greater than the individual poems.

EEC: In reading it, I noticed the variety of styles and visual presentations, so it's great to know that that was kept in mind. Can you discuss the critical and creative heritage influencing the current boom of Hong Kong literature? Was that seen as a reason to do this anthology, and how did this heritage influence you?

JEHL: There’s clearly a confluence of many factors that led to the creation of this particular anthology with its international dimension. There's a lot of creativity and expression coming out of Hong Kong because of external factors; we had Covid, the protests, there's still a lot of anxiety over the identity of Hong Kong as a place and people – a lot of that comes out in poetry. It's interesting that a lot of it is coming out in English, because this speaks to the globalisation of English-language literature. That dovetails with the new expression of writing in English with a Cantonese or Chinese aesthetic to try and ‘glocalise’ Hong Kong Literature. That's the word I would use, glocalise – it's global, but local at the same time.

I think a lot of this comes on the back of the recent success of a lot of poets who we wanted in the anthology. We wanted to get Mary Jean Chan, Kit Fan, Sarah Howe – the UK school – and get people in the US – like Dorothy Chan, Shirley Lim and Marilyn Chin – and put them together into conversation through the publicity, dissemination, and readings. There's a firm connection between a lot of the UK poets and what's going on in Hong Kong, as a lot of them are quite recent immigrants to the UK. With America, there's this interesting tradition of defining yourself as an Asian-American first, so the Hong Kong roots don’t come out as strongly; we wanted to give a lot of the American writers the chance to assert that locality from a distance. It was great because a lot of them obviously have connections to Hong Kong, some of them have spent extended periods in Hong Kong, they've been to the poetry readings, they've helped run many of these things, they've kept in contact with poets in Hong Kong.

The final thing is this new development of a new generation of poetry from Hong Kongers post-2014; people who are thinking about what it means to be a Hong Konger, to be Chinese, to write in the English language, to think about issues of diaspora, migration, identity, culture, conflict, all of that. We were also very much working from what had come out beforehand; the whole collectivity that makes up Hong Kong poetry should be more than one event or one thing, and it should encompass different viewpoints.

Also, we were very clear on inclusivity from the very beginning. We know that there's a very good representation already of LGBT voices in Anglophone Hong Kong Literature, even if it's not stated explicitly. And though this wasn’t conscious, there are two females to every one male poet. There's always going to be our own subconscious biases coming out, but I think it says something about the tradition of where English-language literature in Hong Kong is going. More women than ever are writing, more younger women, more older women, more creative voices in terms of the different racial make-up of Hong Kong. We had poets of different stripes, and colours, and ethnicities. We were not looking to divert or intensify a particular voice or aesthetic, but to constantly add different diversities to it.

EEC: How can others get involved if Where Else or other things inspire them?

JEHL: We are very open to the idea of contributors from any geographical region taking the initiative with doing a launch or a reading – hybrid, virtual or otherwise. Some of the places these were held were also donors, so The Leeds Centre [for New Chinese Writing] with Francis Weightman gave us a very nice donation, which was wonderful, so we’re grateful for that. We also wanted people from Hong Kong to know that if they continued turning up to places like OutLoud[HK 隨言香港] and Peel Street Poetry, then there is always going to be the potential for publication later on.

Tim Tim, when talking about disseminating and promoting this, was thinking about the recently migrated Hong Kongers who might be dealing with culture shock, who might want that sense of what it means to be a Hong Konger in the UK. That was the other thing that we thought about, how we can include a diversity of other Hong Kong voices from, say, the UK, which doesn't have as long a tradition of mass migration as the US. How can we allow people in the UK, even if they're not poets, to gain comfort from the fact that there are voices writing about Hong Kong, in the way that they are? Again, it's more about finding familiarity and identification at the community level. We talked about trying to push this out into non-poetry communities – that will take some time. We talked about Chinatowns, some of the new networks that are being set up. Again, this is all very neutral; it's all about the issue of Hong Kong, Hong Kong's history, Hong Kong's identity. We also thought about how it could be useful for courses as well, such as getting the book onto the syllabus via course instructors in Canada and the US because it's very useful, contemporary, with different community stakeholders, both in Hong Kong and outside.

EEC: The title of the collection is very interesting, and you talk about it in your editor introduction. Can you discuss some of the key aspects of the phrase ‘Where Else’ for us?

JEHL: We were struggling for a title, when Stuart [Bartholomew], the publisher said, ‘Why don't you take a quote and make that the title?’ In the end we were thinking of the two words ‘Where Else’ from Nic[holas] Wong's poem, which Tim Tim had jotted down, and thought that was quite interesting because it can mean a lot of different things: if we say, ‘where else’, it means ‘I wouldn't be anywhere else’, but when you think of it as a question, it says, ‘Where else could be Hong Kong?’ So, we thought that was quite clever.

I find it ironic because when we were going through the unsolicited submissions, there was another poem by Sam Cheuk, with a very interesting quote “‘Where else / Should you be?’ There. Elsewhere.” We had to somehow include that in the structure of the anthology, so I had that as the title for the final section, just to bring home what the term ‘Where Else’ could mean. We were quite happy with it because it's not a conventional title, but we also knew that we needed to subtitle it with something like ‘An International Hong Kong Poetry Anthology’ because we needed the descriptor there. I hope that the title gives a very clear idea that it's not just poets living in Hong Kong. It's Hong Kong poetry spread all over the world.

EEC: In reading the anthology and attending various literary events in Hong Kong, language is always there as a theme, you’ve already mentioned it today, and it plays a huge role and is represented in many ways. How does the Hong Kong context – like its culture and identity – make this interesting? Beyond that, what do you think of language and accent, the aural experience of Hong Kong poetry?

JEHL: Language is the one theme that I think is quite interesting because we're getting a lot more poems that are self-assertively code-switching – and they're not doing it as a fetish or as a way of exoticising Hong Kong Literature, it's just an everyday, lived condition for a lot of people. I think that's great, that's quite unique.

When you look at it beyond code-switching, there's a very pleasing conflation now between the Anglophone and the Sinophone worlds because a lot of the poets writing in English can speak Chinese, and they're reading other Hong Kong poets writing in Chinese. That wasn't always the case. So, some of the metaphors and images are coming from a different literary world, which is great, and that's what we need. In terms of the representation of different accents, as you say, we've got the Cantonese idiom, we've got the written Chinese – which can be classical or vernacular – we've got people who are choosing to use Jyutping [a common romanisation form for Cantonese; Yale is the other most common form of Cantonese romanisation].

EEC: You've got more Jyutping than Yale as well, interestingly.

JEHL: Yeah, we didn't change any of that. We didn't standardise it either.

And then we've got bits of Hakka as well, which is quite interesting. We wanted to engage not just with Cantonese, but to go beyond Cantonese, to Mandarin as well, as we understand that it is now an everyday language in Hong Kong. Frankly, it would be wrong for us not to include some of that. Just the diversity of Chinese in an anglophone poetry anthology is quite remarkable and a good thing as well. That's the language aspect.

As for how it connects to Hong Kong culture and identity, well, we could talk about this all day! Kongish [Hong Kong English, also called ‘Konglish’] is seen as a very interesting way of both internationalising and localising the language for all sorts of reasons, all sorts of different contexts for why that takes place.

EEC: How has this process affected or inspired your own creative and/or critical writings/thinking? Can you pinpoint any of these moments or inspirations?

JEHL: Well, I don't mind being brutal to myself – it's made me realise how out of date some of my writing is! I've been trying to write a collection about Hong Kong the whole time I've been here, and I guess there was a lot of doubt over whether I could genuinely represent certain aspects of Hong Kong lifestyle and Hong Kong culture. There was also this need for me to get the first book about my childhood out of the way, because I wanted a temporality to my work. It's made me realise that there's so much more to write about Hong Kong, but in many ways, you also have to find new ways of writing about the same thing. Stylistically, it's taught me a lot and I've got some ideas on how I can go back to some old poems which are very metrical and chop up the form so that the form helps with the content, not the other way around. In other ways, it's made me more confident of what I am doing because I know that what I'm writing is different from what's in the anthology. Again, it's a case of ‘How do I know that I'm still true to my voice? Well, this is what I'm not.’ It’s a logic of differentiating your own work from others, which has helped me.

Critically, it's really given me a lot of things to think about when I teach at university level. I will include the anthology in my syllabus next year. Students will like that there's a richness in the anthology and how there's a kind of earnestness celebrating Hong Kong identity.

EEC: What's next for you?

JEHL: I want to broaden the current scene of Hong Kong poetry through introducing more opportunities for performance, mixed-media, and community work. I'm thinking of ways of getting some new blood and ideas into OutLoudHK [隨言香港], making sure that the new generation are genuine stakeholders and we're not just putting them in anthologies but making them the driving force for where Hong Kong Anglophone Literature goes in the future; creating international networks because that's how I think Hong Kong Literature will survive. Right now there's still a very small scene in Hong Kong. We need people that come into Hong Kong and then leave Hong Kong staying a part of it.

Interview 2: Tim Tim Cheng

Interview 2: Tim Tim Cheng

Tim Tim Cheng is a poet and teacher from Hong Kong, currently based between Edinburgh and London, and has an MA in creative writing from the University of Edinburgh. Her pamphlet Tapping at Glass was published by Verve Poetry Press in 2023. Her full collection, The Tattoo Collector, is due in 2024. Besides poetry, she translates between Chinese and English, and writes lyrics. For more, see timtimcheng.com and the new podcast on Hong Kong Literature @yshy.podcast on Instagram.

Elizabeth E. Chung: How did you find the process and working relationship with Jenny and Jason?

Tim Tim Cheng: It's been quite an equal process. I took charge of the visuals and the promotional graphics, which were then edited with Jenny’s and Jason’s suggestion. I also tried to save works that might not have made it at first. Some I could, some I could not. As someone who uses English as a second language, I am partial to poems that show potential but are not smooth according to a traditional anglophone standard. I do think, though, it's boring if an anthology just presents ‘the best of the best’ in terms of crafts.

EEC: Yes, to show the full range of what Hong Kong is capable of, what is actually coming out of Hong Kong. That's a really valuable thing to have been doing with this anthology.

What drew you to creative writing and, more specifically, poetry?

TTC: I've been writing blogs since I was very young. I started officially writing poetry at Baptist university, where I met teachers who are also writers. I struggled with essays. The logic of making everything critically viable does not encapsulate what's happening in real life and in my brain. Writing poetry could make space for things that are valuable but not academic yet. I find facts really hard to grasp. I don't remember the details. I don't remember names and years. But in a poem, I can try to capture the emotions surrounding those facts, numbers, and names. That's a way to help me try to learn and stay historically informed.

EEC: How does the editing process impact – or how has it impacted – your creative process?

TTC: I have taught band 1-3 students in different school settings, so I always think about what makes poetry accessible.* I thought that simplifying poems could help but during the editing process, I started to reflect on that idea. Instead of being afraid of complexity, maybe some complexity could attract people. Eric Yip’s poems are a great example because they are quite complex in terms of linguistic play and contexts. When his poems were being promoted [after he won the 2021 National Poetry Competition], a lot of people were like, ‘It won a prize, it must be good. Oh… I don't understand it. Now I must understand it.’ There were tons of videos and articles on how to decode Eric’s poem ‘Fricatives’. That really blew my mind. What does it mean to reach people? Do we need to establish the best of the best so that people learn and aspire to a certain standard?

Also, I remember how hard it is to try to understand a piece of literature without any assurance that you might know every word, every reference. That went into my editing process as well. How do I make sure that a random Hong Kong person who knows nothing about English poetry could still flip through the book without fear and find something that they could resonate with? With this in mind, I included artwork created by Hong Kong artists and shorter poems. I hope that by doing that, people will say, ‘Okay, this book isn’t as posh as I thought.’

EEC: I think that's important and, as you mentioned, it’s really contextual how complex you do or don't want a poem to be. If we’re talking about Eric, he wrote for a national competition, that is a very different context to publishing something in a zine, for example. It's a completely different purpose, so it's got a completely different depth, and you're asking something very different of your audience as well.

TTC: Yeah, and I must admit that when I started writing, my intended audience was simple and direct. My thought process was: “Hong Kong is going through things. I'm going to write that.” I was trying to inform an audience who didn't know about the happenings from a local perspective. But the more I wrote, I didn’t just want to be informative. Now, I almost want to get rid of the audience. That's how I started writing eco-poetry, trying to stay away from the human audience.

EEC: Do you relate to Hong Kong Literature as a broader field? If so, how?

TTC: I don't even know if I'm super familiar with Hong Kong Literature… I do think I wrote mainstream topics from the start but then I was told by some readers that I was writing from the periphery, that my English writing contains Cantonese syntaxes. I was like ‘That's nice. I like that.’ I guess in some way, some readers with Hong Kong connections are looking for local elements and perspectives, which is not unlike bingo. You need to hit certain markers and sentiments, then those readers would be happy in the sense that they felt seen, their daily experiences being affirmed.

From a broader perspective, people without a Hong Kong connection are also interested in Hong Kong stories. I remember going to festivals in Scotland. I struggled with how much information or explanation I needed to give. I would usually do some irrelevant rambling and then say, ‘None of this is in the poem, but the poem arose from this context.’ I've had audiences who are from other politically troubled places, who come up to me after a reading and say, ‘I could relate to that.’ In the end, our struggles are embedded in interconnected networks. A description of a faraway place could shed light on what is close to you.

That said, this could also be frustrating because I know writers who strategically go beyond the overtly political in an attempt to broaden up Hong Kong writing. But some readers with fleeting interests might just regard and limit Hong Kong writing to case studies.

EEC: I like that you mentioned Hong Kong being seen as peripheral or writing from the periphery in some way, because I always think that to write about “Hong Kong” is “peripheral”...

TTC: I'm literally writing about food. Everyone eats. That's not peripheral!

EEC: Yes, but because it's got this relationship to ‘some other place’ that isn't what everyone centres their mind on, it's got this other label.

TTC: I remember saying the wrong thing at the StAnza Festival in Scotland. It might not even be ‘wrong,’ but I was aware that it might be strange or inappropriate. I told the audience that when I first started writing, or when I first started looking to the UK, I always worried that I don't sound ‘white enough’. Then I realised that, ‘God, I'm talking to a predominately white audience. What am I doing?’ – Then I realised that I was actually thinking of whether I sounded English enough. It’s ‘Englishness’ more than ‘whiteness’. Then I remembered that, of course, Scottish people also share my concerns on language and power. Did I assume they wouldn’t understand me because I was too caught up in where I come from?

EEC: Yeah, it's constantly on your mind though when you're in different spaces or ‘unusual’ spaces.

TTC: Yeah. Some white writers I know also regard themselves as writing from the periphery, especially if they are from regions and/or backgrounds that are under-represented. Perhaps we are at the periphery when we feel out of place.

EEC: Or, even if you haven’t started writing. If you have a central idea, how you present it or the nuances of how you say something sets you apart. That's the interesting thing about literature.

TTC: Yeah. When people know that you're writing in English, they often assume that you have a wider audience because English is more widely spoken– yes and no. Local people don't really recognise you as a Hong Kong writer most of the time. If you see coverage on Hong Kong Literature, very rarely do they include English writers. I remember being included in one of the panel discussions organised by Louise Law [Lok-Man, 羅樂敏, lo4 lok6 man5], who is a poet, writer, facilitator, and an organiser. The panel was called 如何用外語寫好香港 [jyu4 ho4 jung6 ngoi6 jyu5 se6 hou2 hoeng1 gong2] “How to write Hong Kong in the foreign language”. Perhaps, English is still very foreign, especially as a literary language in Hong Kong.

EEC: What does the title of the collection, Where Else, signify for you? I believe you’re the one who came up with it.

TTC: Yeah, I did. We were frustrated because we couldn’t really summarise the book. I looked at Nicholas Wong’s poem [‘Reflection’], which is a creative translation of Mirror’s lyrics [for the song ‘Innerspace’]. A line goes: ‘Where else, if not the sky,’. I only realised later that so many books from the diaspora are about ‘elsewhere’. I didn’t know that I was trying to do something different. At a launch event of the anthology with Kit Fan [a Hong Kong poet and novelist based in the UK], he said ‘Where Else is a nonsensical title’. I liked that.

For a long time, I could only write about Hong Kong; I could not write about anything else until I moved to Scotland. ‘Where else’ is a way for me to express that Hong Kong is an imperative.

EEC: This might be quite a big question, it’s four-in-one: I know you're fluent in Cantonese and that a number of the poems code-switch, use Chinese characters, or imply an accent – but there are very few footnotes. Why is this? Did you make a conscious effort to choose pieces that mixed languages, accents, and Englishes? And, why? What is the power or significance of that?

TTC: We try to respect the poet’s intention; if the poet does not include footnotes, we don't ask them to. Historically, it's always, ‘Oh, you're from a ‘minor’ culture, ‘the periphery, you have the responsibility to teach and explain to people ‘in the centre’.’ What about no! We are exhausted and the reader can do the work. That said, I also appreciate writers who choose to include footnotes. There is an openness to this when both sides are willing.

Nicholas Wong talked about how frustrating it could be when he came across French words in English poems. Putting Chinese words in English poems could flip the power dynamics a little. I am also thinking of Louise [Leung Fung Yee]'s poems, which would be quite inaccessible to people who don't know Cantonese. But the way she performs is so powerful there is no need to understand every word. She's doing great things outside of the paradigm of Anglophone poetry or Anglophone publishing. Like, I don't need you to fully understand me, but I demand my presence in this space.

EEC: I think it's really interesting that you mentioned French, because you're right, people will use languages like French and Spanish but those are also interesting choices in themselves; many other languages would stand out visually a lot more, for example, Chinese characters within English words or an Anglophone framework or context. But why are so many of them read as having a political significance, or as if they're making a statement when really, it's just that this is the language the author knows? It can be as basic as that.

TTC: Multilingual poetry is politicised because it’s still not visible enough. The day it is no longer special is the day we will have finally done our job. I am thinking of one contributor, Sophie Lau. Their poetry is full of multiple languages because they're polyglot. They rhyme across different languages. You can hear all the echoes and resonances. Even if you don’t understand the languages, you still enjoy it. That’s the fun bit, that's almost restoring poetry to its original function when it's all about the sounds and rhythm. I think what we're doing might be considered as new, but it's also kind of returning to what poetry is supposed to be.

EEC: I thought you'd find this funny because you mentioned Louise. This is my annotated version of her poem [showing my version of the poem to the camera, with my annotations and translations covering more of the page than her poem].

TTC: Oh, I read that last night [at a launch of the anthology]. For most of my life, I tried to get rid of my Hong Kong accent. When I read that poem, I was trying to restore it. It was liberating. I do know that some diasporic artists think that it's outdated to do an Asian impression with an accent, while some say there's nothing wrong with the endearing stereotype.

EEC: How did it feel writing and editing works about a place you weren’t physically at, especially Hong Kong, which is a place so closely related to your own life?

TTC: I had always written about Hong Kong when I was in Hong Kong. I made the decision to learn how to write to an industry standard in the UK. Both experiences are necessary for me. When I'm in Hong Kong, I get to write from first-hand experiences. When I'm away from Hong Kong, I can crystallise the emotions better. I can extract more transcultural meanings with the distance.

Half a year into living in the UK, I started writing about flowers and plants and being more Chinese than I have ever thought. I wouldn't be able to write those things if I was in Hong Kong. I do live with the fear that the longer I live in the UK, the less I will be in touch with Hong Kong. It means that what I write will not catch up with the city’s development. Will that make me irrelevant? It’s scary and almost unthinkable. But you don't have to stick to a single identity. You can do different things.

EEC: That’s a very interesting perspective. It's something I've never considered. My immediate reaction is, ‘No, what? If you choose to be a Hong Konger and you want to write about Hong Kong, of course you can!’ but I've never thought about it as you’ve just described. That's going to take some time before I have a response.

TTC: I do risk sounding narrow-minded here, but I do think that some people do have more say than others as to who qualifies as a Hong Kong writer. I also believe that being aware of your (eventual) irrelevance is a generous act, not necessarily to yourself, but to emerging voices.

EEC: Well, humanity really has a thing about labels.

TTC: Yeah, the labels fail us, but they do exist. It’s funny how sometimes I am called a HK poet in the UK, and an English poet in HK. But I also think of Chinese migrants who made their names as Hong Kong writers, Hong Kong writers who made it in Taiwan, their new ‘home’.

EEC: So, my last question: What's next for you?

TTC: I’m making a podcast with Eric [Yip], Louise [Leung Fung Yee] and Felix [Chow Yue Ching, another Hong Kong poet included in the anthology]. It's a Cantonese podcast that focuses on global Anglophone poetry. I'm working on my full collection The Tattoo Collector, which stretches from across Hong Kong, Scotland, London and beyond.

Elizabeth E. Chung (she/they) completed her undergraduate degree in English Literature and Theatre Studies (International) at the University of Leeds, an exchange year at the University of Hong Kong, and her MPhil in English (Literary Studies) at the Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK). She is continuing her research on Hong Kong Literature through her PhD studies at CUHK. Her poetry has been published by the University of Leeds in their 2022 edition of Poetry and Audience, in the 2023 publication Where Else: an International Hong Kong Poetry Anthology, and in the online journal The Signal House Edition. She can be found online @chungyilei and at OutLoudHK隨言香港 every month.

*Note: In Hong Kong, every school is attached with a ‘band’ qualifier: 1, 2, or 3. Within each band, a letter is also assigned, A, B, or C, where 1A schools are the most prestigious. Cheng later told me that unless you attend a Band 1 school, you have no exposure to English literature at all.

Note: All Romanisations have been made with reference to the CC-Canto database.