Guest blog: Nick Stember - October 2019 Genre Fiction Symposium

We're very grateful to Nick Stember for providing this great write-up of our symposium! Nick is a translator and historian of Chinese comics and science fiction, currently working on a PhD on early Reform-era lianhuanhua (comic books) in the Faculty of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies at the University of Cambridge. Follow him on Twitter @beckminster. We'd also like to thank the Sino-British Fellowship Trust for their support with this event.

(NB: For a summary of our symposium and keynotes in Chinese, please see Lyu Guangzhao's report on Wechat.)

This past weekend I had the pleasure of attending the “Genre Fiction in Contemporary China, and its Reception in the West” symposium at the University of Leeds Centre for Contemporary Chinese Writing. It was the second event that I've attended at the Centre, the first being the Reading Chinese Book Review Network Residential Weekend two years prior. During that first visit we had had some great discussions about contemporary Chinese fiction, experimental writing from Hong Kong, children's literature, and the messy business of translating all the above. I remember being particularly impressed with the roster of guests, which included readers, authors, translators, students, and scholars, and also how warm and welcoming our hosts at the University of Leeds were, encouraging us to share our unique perspectives with the other attendees. Bringing everyone together like this really highlighted, for me, the social nature of the publishing industry, and was definitely one of the highlights of 2017.

This past weekend I had the pleasure of attending the “Genre Fiction in Contemporary China, and its Reception in the West” symposium at the University of Leeds Centre for Contemporary Chinese Writing. It was the second event that I've attended at the Centre, the first being the Reading Chinese Book Review Network Residential Weekend two years prior. During that first visit we had had some great discussions about contemporary Chinese fiction, experimental writing from Hong Kong, children's literature, and the messy business of translating all the above. I remember being particularly impressed with the roster of guests, which included readers, authors, translators, students, and scholars, and also how warm and welcoming our hosts at the University of Leeds were, encouraging us to share our unique perspectives with the other attendees. Bringing everyone together like this really highlighted, for me, the social nature of the publishing industry, and was definitely one of the highlights of 2017.

While this year's event proved every bit as diverse and enjoyable as the last I attended, as a translator and historian of Chinese comic books and science fiction, the theme was understandably a little closer to home. The event was kicked off with a short welcome from Frances Weightman who, setting aside for the moment the pesky debate between "genre" and "literary" fiction, asked us instead to consider whether literature that is popular in translation must also necessarily be popular in China. Dr. Weightman's question would prove to be one to which we would return to throughout the course of the conference, with (like those posed to the appropriately-named supercomputer "Deep Thought" in Douglas Adam's Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy) seemingly no easy answers in sight.

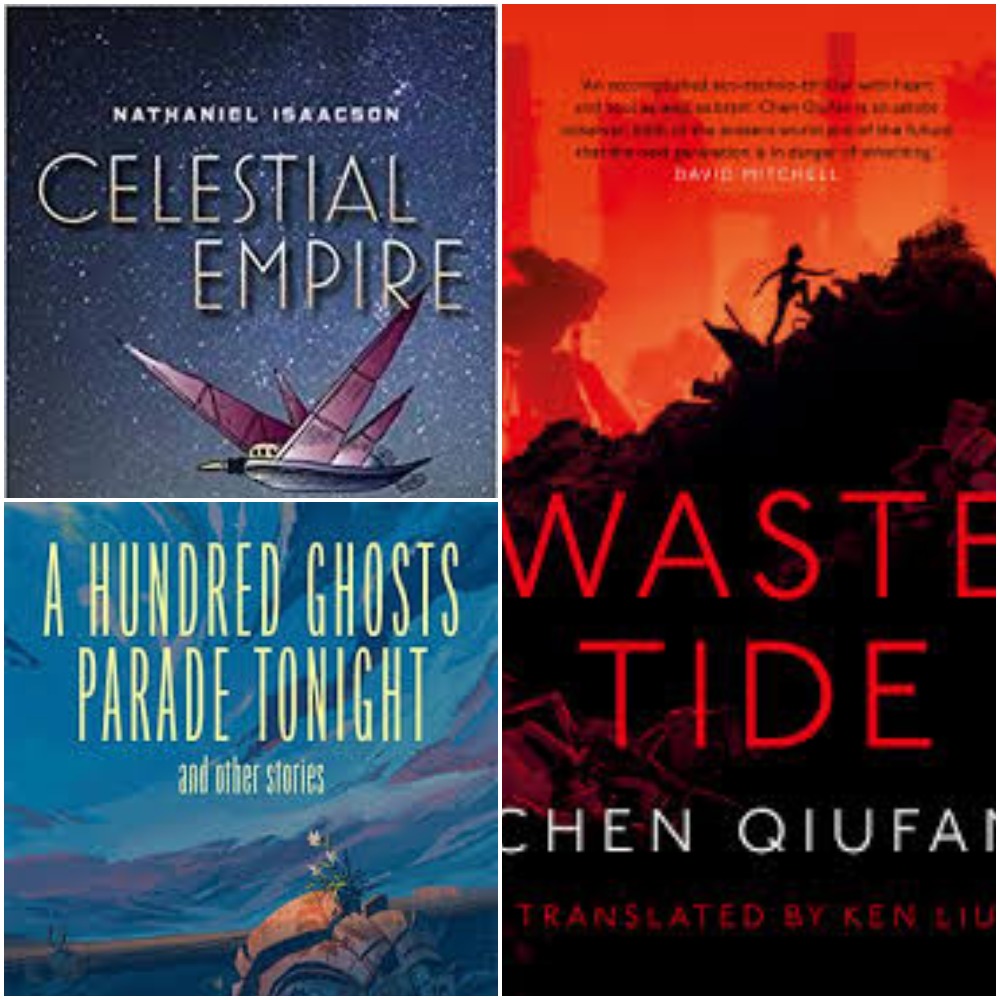

The first talk, by Nathaniel Isaacson, on the topic of "The Aesthetics of Development in Late Qing Visual Culture: contextualising contemporary science-fiction", began with Dr. Isaacson’s recent work on the 2018 science fiction film The Wandering Earth (in turn an adaptation of a 2000 novella by Liu Cixin) before taking a deep dive into the late Qing illustrated pictorial Touch-stone Studio (Dianshizhai, largely illustrated by Wu Woyao), suggesting a complimentary anthropogenic reading of the two texts, from steam trains to petro-fiction in twinned ages of dramatic environmental and cultural change. Liu Cixin and Wu Woyao's respective critiques of industrial capitalism, Isaacson argued, could be seen as versions of Lu Xun's memorable metaphor of the Iron House whose victims cannot escape, but know not of their impending doom. Should the author call out to them? Further linking the two in the subterranean depths of the gestalt with a discussion of Han Song's disturbing 2010 novel Subway (Ditie), Isaacson suggested that " aestheticization of transportation" and "grotesque bodies in repetition" mirror not so much Kafka's bureaucratic nightmares as they do Benjamin's fascist reality.

In the second talk, Chen Qiufan, or Stan, as he introduced himself, discussed the intersection of reality and fiction in his recently translated novel. Titled "Behind and Beyond the Waste Tide", Chen shared pictures from his first visits to the e-waste recycling villages of his home province of Guangdong, taken over a decade ago. Providing some much needed optimism, these were shown to compare favorably with the more recent standardization and regulation of the industry, but with much work still to be done, both at the individual and institutional level. In particular, Chen shared examples from his own work promoting the French-produced environmental documentary Deep Blue through an exhibition of "garbage art", arguing that if we want to change the world, we need to first change our mindsets. During the Q&A which followed, Chen provided an example of this in his own creative life, discussing some of the ways being translated has forced him to rethink his writing, in particular the depiction of sexual violence against his female protagonist. After discussions with his editor and translator, Chen ultimately rewrote the scene, finding the new version a much better depiction of the psychological terror of our posthuman future.

In the second talk, Chen Qiufan, or Stan, as he introduced himself, discussed the intersection of reality and fiction in his recently translated novel. Titled "Behind and Beyond the Waste Tide", Chen shared pictures from his first visits to the e-waste recycling villages of his home province of Guangdong, taken over a decade ago. Providing some much needed optimism, these were shown to compare favorably with the more recent standardization and regulation of the industry, but with much work still to be done, both at the individual and institutional level. In particular, Chen shared examples from his own work promoting the French-produced environmental documentary Deep Blue through an exhibition of "garbage art", arguing that if we want to change the world, we need to first change our mindsets. During the Q&A which followed, Chen provided an example of this in his own creative life, discussing some of the ways being translated has forced him to rethink his writing, in particular the depiction of sexual violence against his female protagonist. After discussions with his editor and translator, Chen ultimately rewrote the scene, finding the new version a much better depiction of the psychological terror of our posthuman future.

In the third talk, Wang Yao (aka Xia Jia) took “The Mad Man as Hero in Chinese Sci-fi” as her topic. Beginning with Tom Godwin's short story "The Cold Equations" on the limits of human compassion in the depths of space, Wang then turned to Ursula K. LeGuin's equally well-known version of the "Trolley Problem", "Those Who Walk Away From Omelas". Whereas Godwin's story ends on a dark note, however, Wang pointed out that in "...Omelas" there is at least the possibility of "walking away." These two stories in turn provide a counterpoint for Liu Cixin's 1999 story, "The Collapse of the Universe", in which his recurring character, the acerbic scientist Ding Yi, discovers that the end is, quite literally, nigh. As life on not only planet Earth, but the entire universe will soon cease to exist, Ding Yi points out the death of any individual no longer matters -- hardly a comfort for a character who is grieving for her recently deceased father. In Ding Yi, Wang finds echoes of Lu Xun's "Diary of a Madman", in which the titular protagonist becomes convinced that he is surrounded by cannibals. Not unlike this memorable critique of Confucian morality, Wang finds that madmen in Chinese science fiction are a common thread through the "core" authors of genre.

In the afternoon, two roundtables were held, the first on "The Reception of Chinese Science Fiction in the West", featuring Chen, Wang, and Isaacson, in conversation with Lyu Guangzhao, Yen Ooi, and Sarah Dodd. Beginning with Yen, who discussed her complicated reading of Chinese SF as a self-identified passive bilingual second-generation immigrant to the UK of Chinese-Malaysian descent, participants in turn discussed the various challenges faces by Chinese science fiction, with particular emphasis placed on the key roles played by the indefatigable ("Buddha-like") translator and author, Ken Liu, in addition to ("cyborg-angel") Neil Clarke, editor of Clarkesworld Magazine. The second roundtable, "Translating Genre Fiction", featured Emily Jones, Nicky Harman, Michelle Deeter, Brigitte Duzan, and myself. Kicked off by Deeter, the motley crew of translators discussed a variety of issues relating to the nuts and bolts of translating of commercial fiction, concluding with a frank discussion of the nigh impossibility of making ends meet on the translation of Chinese fiction into English alone.

The second day of the symposium began with a talk by Jeff Kinkley on “A Popular Genre: The ex-China mystery novel”, providing a lively account of an understudied genre. Considering first the various varieties of genre fiction available in English, Kinkley then discussed the four major genres of fiction in the late Qing, as proposed by David Der-wei Wang in his ground-breaking study Fin-de-Siècle Splendor: Repressed Modernities of Late Qing Fiction, 1848-1911: depravity romance, grotesque exposé, chivalric and court-case cycles, and science fantasy. In Kinkley's reading, these can be seen as antecedents not so much of the modernism of the May Fourth New Literature movement, but rather of the multitudinous selection of online fiction produced over the last three decades -- with the notable exception of the "almost completely defunct" genre of anti-corruption literature as latter day heir to court-case fiction. Turning instead to Anglophone detective fiction set in Chinese, Kinkley provided an analysis of the two types of protagonists in these novels: professional Chinese detectives heroes; and beset, out-of-place adventurer heroes. This led into a discussion of the relationship between the respective heroes, which Kinkley argues is the central concern of this fiction.

The second day of the symposium began with a talk by Jeff Kinkley on “A Popular Genre: The ex-China mystery novel”, providing a lively account of an understudied genre. Considering first the various varieties of genre fiction available in English, Kinkley then discussed the four major genres of fiction in the late Qing, as proposed by David Der-wei Wang in his ground-breaking study Fin-de-Siècle Splendor: Repressed Modernities of Late Qing Fiction, 1848-1911: depravity romance, grotesque exposé, chivalric and court-case cycles, and science fantasy. In Kinkley's reading, these can be seen as antecedents not so much of the modernism of the May Fourth New Literature movement, but rather of the multitudinous selection of online fiction produced over the last three decades -- with the notable exception of the "almost completely defunct" genre of anti-corruption literature as latter day heir to court-case fiction. Turning instead to Anglophone detective fiction set in Chinese, Kinkley provided an analysis of the two types of protagonists in these novels: professional Chinese detectives heroes; and beset, out-of-place adventurer heroes. This led into a discussion of the relationship between the respective heroes, which Kinkley argues is the central concern of this fiction.

Kinkley's talk was followed by three roundtables, the first on "Reading 'Genre'", with Kinkley, Duzan, Harman, and Helen Wang, in addition to myself. Discussion ranged from the (figurative and literal) low status of SF in France to questions about the sustainability of the current Chinese SF boom, with segues into the curious case of the (largely) missing Chinese detective novel. In the afternoon, two guest speakers, Nicholas Cheetham and Laura Palmer from Head of Zeus spoke on the topic of of "Publishing Genre Fiction ~ the UK market", providing a fascinating peek into the origins of their press, and their circuitous route to publishing Chinese science fiction, and more recently, crime fiction. This was followed by a short presentation by Daniel Li from Alain Charles Asia Ltd, discussing their work in marketing authors such as Feng Jicai and Jia Pingwa.

Kinkley's talk was followed by three roundtables, the first on "Reading 'Genre'", with Kinkley, Duzan, Harman, and Helen Wang, in addition to myself. Discussion ranged from the (figurative and literal) low status of SF in France to questions about the sustainability of the current Chinese SF boom, with segues into the curious case of the (largely) missing Chinese detective novel. In the afternoon, two guest speakers, Nicholas Cheetham and Laura Palmer from Head of Zeus spoke on the topic of of "Publishing Genre Fiction ~ the UK market", providing a fascinating peek into the origins of their press, and their circuitous route to publishing Chinese science fiction, and more recently, crime fiction. This was followed by a short presentation by Daniel Li from Alain Charles Asia Ltd, discussing their work in marketing authors such as Feng Jicai and Jia Pingwa.

The final roundtable of the conference, "New Research in Genre fiction" saw Shan Xiaodan, Lyu Guangzhao, Peng Qiao, and myself presenting our work as graduate students, with Shan presenting on the English language reception of Jin Yong's novels, Lyu on the Foucauldian heterotopias of Chen's Waste Tide, Peng on the origins and development of the online fiction portal Qidian, and myself on the illustration of Chinese comic books during the early-Reform era.

As the last event of these two very full two days, a banquet was held to celebrate the launch of Writing Chinese: A Journal of Contemporary Sinophone Writing, a new journal from the Centre, complete with readings by Chen Qiufan and Xia Jia, followed by a Q&A session hosted by Sarah Dodd. Toasts were made, drinks imbibed, and with that, the event drew to a close. That such a complicated event, with so many moving parts, could go off without a hitch, is truly a credit to the Centre and its staff (particularly the youngest members, who contributed hand-drawn "Time's Up!" cards), and I look forward to seeing it go from strength to strength in the years to come.

14 October 2019