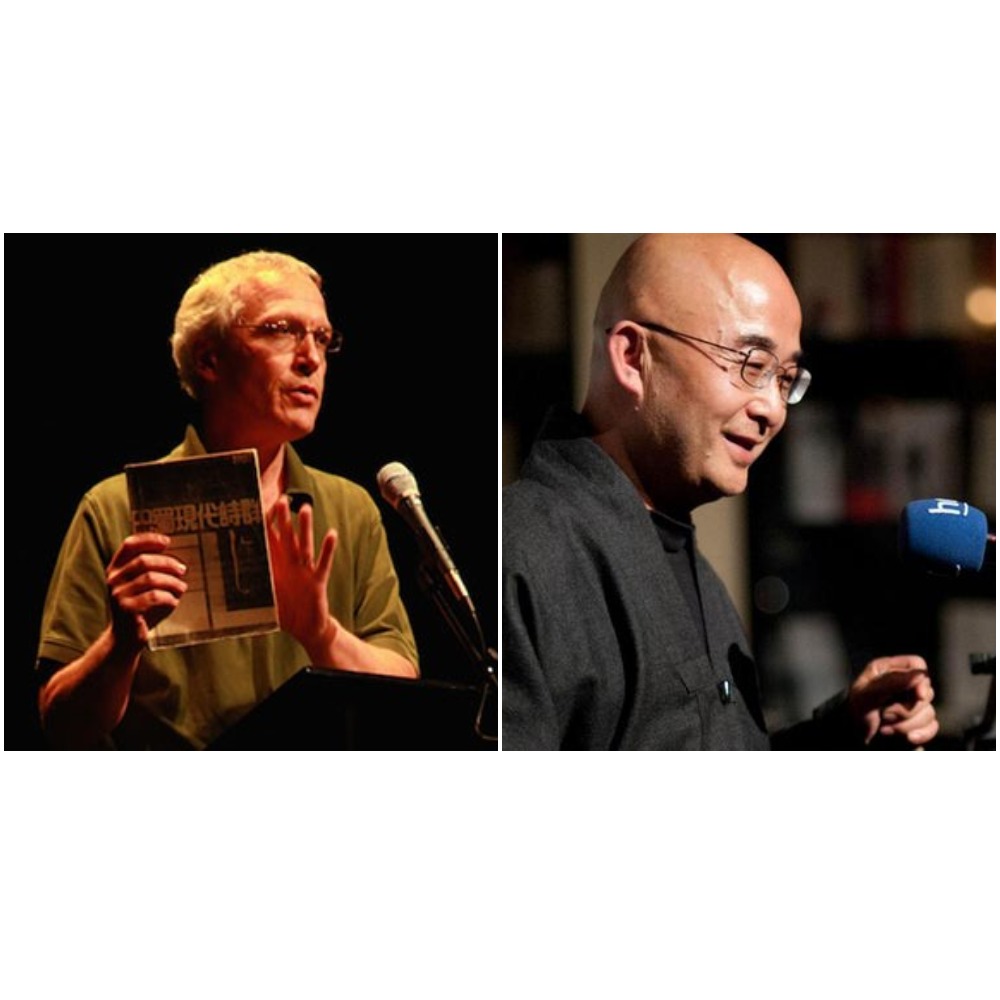

Talking Translation: Michael M. Day

In the latest of our series of interviews with translators, we're very happy to be joined by Michael M. Day, whose translation of Liao Yiwu's 廖亦武 'City of Death' is featured on our book club this June. As well as being a translator of Chinese poetry and fiction, Michael is an associate professor at National University in San Diego. His book, China’s Second World of Poetry: The Sichuan Avant-Garde, 1982-1992, is available here. Below, Michael tells us about his adventures in poetry, translation, and academia.

Can you tell us how you got started in literary translation? (And what was it that drew you to 'the unofficial grey areas' of Chinese culture, as you say in your book on the Sichuan poetic Avant-garde?)

It all started in the “grey areas”, I suppose…. In 1984, after returning to Vancouver, Canada, from spending 2 years as a cultural exchange scholar at Shandong University and Nanjing University, a local Chinese friend of mine came to me with a translation project. She had spent those 2 years as a student at the Beijing Language Institute and had made a number of local friends, including the poet Yan Li 严力. Yan had been published in Bei Dao’s Today magazine and, previously, had spent time in prison in early-1976 as a result of taking part in the illegal public commemorations of Zhou Enlai on Tian’anmen Square… he met many other poets in prison, which led to his later connection with Today poets, etc and so on. That’s about as “grey” as it gets, eh.

Anyway, this friend of mine told me that Yan had just successfully immigrated to New York and had asked her to translate his unpublished poetry collection, The Flying Dictionary 飞越字典. She knew I was a bit of a poet and felt my reading Chinese was better than hers, so she asked me to do the job…. And I did. And I think it sorta sucked (I’m afraid to look at it, or even look for it… it’s either here in San Diego in my storage shed or in a box under my mother’s living room on Vancouver Island. Who knows what Yan Li did with it.).

But this was sort of a false start…. As I think my next translations were of 2 short stories by Hong Feng 洪峰 and Chen Jiangong 陈建功 my then-MA advisor asked me to do for a book he was editing (Worlds of Chinese Fiction, edited by Michael S. Duke, M. E. Sharpe: 1991). There was nothing grey about these 2 guys.

That all changed in 1986, after I returned to China without finishing or even starting my MA thesis (I wouldn’t finish it until a year or so after I was expelled from China on October 30, 1991). I was off to China to live and be a poet etc…

That was the general idea, anyway… though I was working as an English teacher and then as a translation editor and translator for the next 2 years. But in 1986, my Canadian Chinese friend was back in Beijing and had a local boyfriend who was a painter … and he was also a good friend of Liu Xiaobo, whom I met for the first time.

During my MA studies I was very interested in the Today Group of poets, of course, but not enamored enough to write an MA thesis about them (the subject was already done to death etc.). That said, I read all the published “avant-garde/modernist” poetry I could find … and the Fall and Winter of 1986 was a very good time to be reading such poetry in China in official literary journals (I subscribed to a few, hunted down others), as all sorts of previously unpublishable poetry was getting published. Interesting times…. that came to a crashing halt in January 1987 after democracy demonstrations by students and the fall of Party Secretary General Hu Yaobang (for allowing all the “bourgeois liberalism” to occur). Specifically banned was the combined January-February issue of People’s Literature, and a few of the writers therein, among them fiction writer Ma Jian and the poet Liao Yiwu. Liao’s poem was “The City of Death”, and this was the first time I took note of Liao’s name.

Later, after I’d moved to Beijing in August 1987, Liu Xiaobo gave me a copy of a banned “unofficial” poetry journal from Sichuan, thinking I’d be more interested in the contents than he was…. And it featured another long poem by Liao and the journal was also edited by him. I wrote Liao a letter introducing myself and asking if I could come and visit. And with this I descended through the grey into outright black, I suppose…. Liao being blacklisted at the time.

Any more on this and I’ll be rewriting my eBook/doctoral thesis etc…. it’s all there at DACHS, if anybody’s interested.

What have been some of the most rewarding aspects of translating Liao Yiwu's poetry? Did 'City of Death' present particular challenges for a translator?

I think the rewards and the challenges are linked… namely Liao’s seemingly free-ranging surrealistic imagination and expressionism. One also needs a good knowledge of the historical period he’s dealing with (the Cultural Revolution), something I was already equipped with. I suppose I felt emotionally engaged with his writing style and subject matter…. Which might be something some poets and translators have problems with: emotion, especially extreme emotion. It’s difficult to find an appropriate register etc. I’m guessing, though I don’t remember if I had such a difficulty at the time (I’m guessing I didn’t). In any case, this seemingly unbridled style is one of the things some critics in China (and elsewhere) find as a weakness of Liao’s poetry … and I consider it a strength, actually. Considering such to be a weakness seems indicative (to me, anyway) of how far poetry has travelled from its original lyrical origins and impulses. So, erm, yes… this’s me volunteering myself as a target for those who don’t like this sort of poetry.

Are there other contemporary Chinese poets whose work you would recommend for people wanting to find out more?

Well, to beat my old drum, there’s the anthology of poets and their poetry I’ve placed in DACHS, 20-40 poems from 20 poets. I undertook this translation project during 1993-1997, as part of my MA and doctoral work (my MA thesis was a focus on the persons and poetry of 3 Sichuan poets: Liao Yiwu, Li Yawei 李亚伟, and Zhou Lunyou 周伦佑). Seven of the 20 poets are from Sichuan and are dealt with extensively in my eBook, but the other 13 also appear at times and played important roles as avant-garde/unofficial poets and activists during the period covered by the eBook (primarily 1983-1993). A good number of these poets remain active and highly influential in China’s poetry scene today, much of the post-1993 poetry readily accessible and translated and published outside of China.

There are a good number of younger poets (and other writers) who are worth reading, and I highly suggest that people look to Paper Republic for news and translation there… I’m guessing that many readers here will be familiar with this site… oh, and by the way, the Michael Day listed there is not me, which is why I go by Michael M. Day or Michael Martin Day… there are a couple of other Michael Day’s who translate from Chinese etc).

What made you decide to publish both your translations and your academic work in open-source format?

I do poetry…. Nobody makes money off it (or nobody should, anyway… ‘cause the poets sure ain’t), and I want whoever is interested in poetry and the history of poetry in China to have free and easy access to my work. Otherwise what would be the point of doing all the work? At least that is what I told myself, and part of the reason why I stopped working on my doctorate in 1997 (when I fled Vancouver for Prague)… thinking it was all largely pointless, until Michel Hockx and Maghiel van Crevel convinced me otherwise and I was given the opportunity to put all my stuff online by DACHS Leiden. Instead of 2 massive books costing an arm and a leg (if I’d ever found publishers), it’s all out there for anybody interested to dive into to whatever depth their interest takes them. Hurrah! No?

Do you have any advice for people just starting out in literary translation?

Learn Chinese well, live in China or Taiwan or Hongkong for as long as you feel necessary, and go wherever your interest takes you (in terms of reading literature etc)… ignore the literary critics when doing this, if at all possible. Make your own discoveries … internal and external.

Can you tell us anything about what you’re working on at the moment?

The new (and 1st) book of Liao’s and mine is now out through Barque Press. It's called Love Songs from the Gulags, and is a collection of 30 poems, some letters, etc Liao wrote while imprisoned, 1990-1994. The original Chinese text can be found at DACHS under the title《犯人的祖国》.(The only texts in the book not found in the DACHS text are the long poem and the essay about Liao and me at the end of the book… but I’ll provide the original texts of those (or the whole thing) to anybody who asks me for them: mday@nu.edu).

Otherwise, I’ve just finalized, sort of, the translation of the text of an essay about Liu Xiaobo that Liao Yiwu has written for the Washington Post that may be published on the anniversary of Liu’s death (July 13). Otherwise, thinking about whether there’s any point in continuing the translation of Liao’s first novel, already translated and published in German and French, I believe… this because of English readers’ general shunning of translated literature (with a very few exceptions) and the surrealistic etc nature of Liao’s prose (like the “City of Death”, eh…. only 300+ pages of it… publishers etc. in North America not much interested, Liao and my literary agent advises). With 2 wee kiddies and now full Professor, I’ve not too much time to spend of translating long novels on spec… sorta wish I did though. And then there are the 200 or so long, detailed letters I wrote as I wandered about in China from April until December 1989…. There’s something there of value, just not sure how to deal with it all yet.

Thank you so much for taking the time to answer our questions!