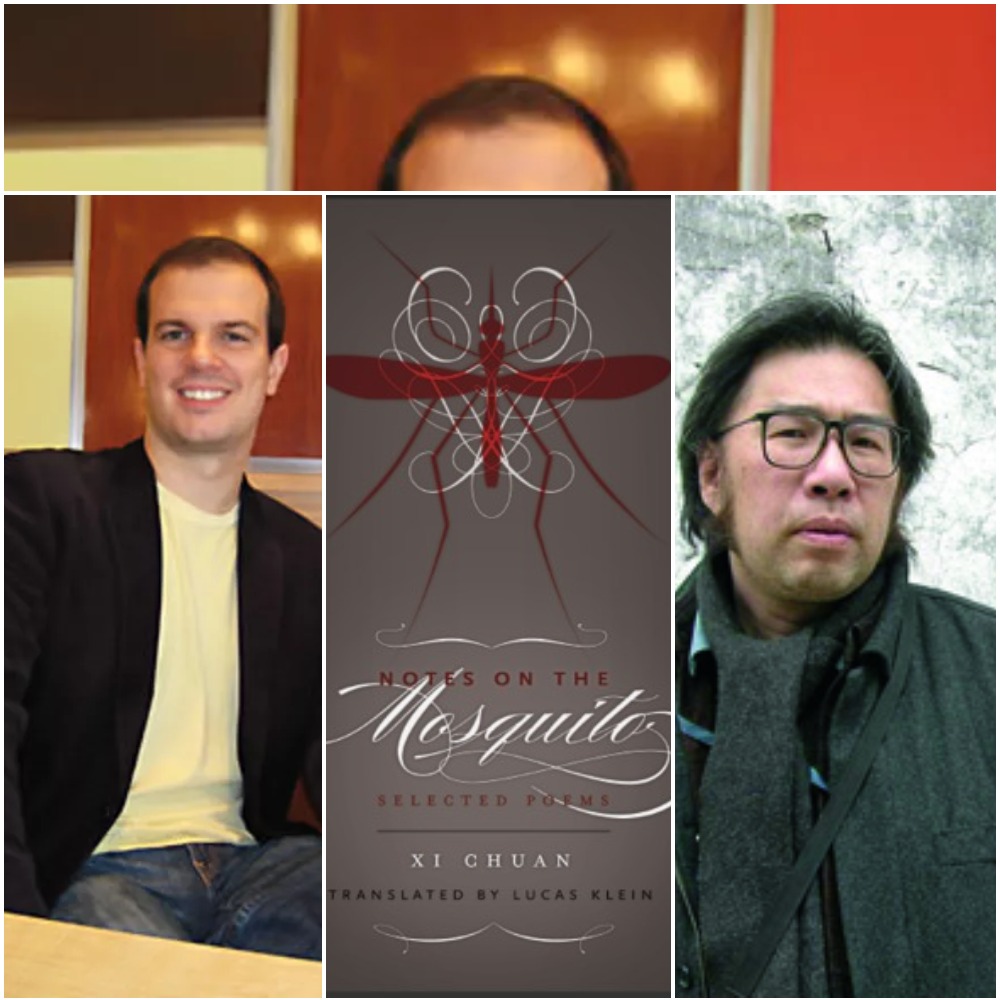

Talking Translation: Lucas Klein

In the latest of our series of interviews with translators, we're delighted to be joined by Lucas Klein, who tells us more about his work, and in particular his much-lauded translation of Xi Chuan's poems, Notes From the Mosquito. Xi Chuan was author of the month on our Book Club in October 2018, and you can read more about him, along with Lucas's translations, here. Lucas also has a fantastic website, which is vital reading for anyone interested in Chinese poetry.

What got you started in literary translation?

As an undergrad I did a double major in Literary Studies and Chinese; I also took a few creative writing classes. The combination of literary analysis and creative writing was satisfying for a number of reasons, because it allowed me to combine the analytical with the creative parts of my interest in literature, but there were frustrations, too. At about this time someone who knew my interest in Chinese poetry gave me Eliot Weinberger’s Nineteen Ways of Looking at Wang Wei, and I knew that translation was something I needed to try. The frustrations I was referring to were along the lines of: the creative writing classes were often too touchy-feely for me, whereas the other literature classes I was taking could be too dry. Weinberger’s Nineteen Ways convinced me that I could integrate the two approaches further—while practicing what seemed to me the hardest kind of writing available. If it’s not difficult, why do it? But it’s a fine point: a lot of people talk about poetry translation being “impossible”; it’s not impossible—it’s just difficult!

How do you choose your authors and projects? (Or do they choose you?)

I translate mostly classical Chinese poetry and contemporary Chinese poetry. The classical Chinese that I’ve translated I’ve found: I’ve come across existing translations and said, I’m not quite satisfied with what others have done, so let me see if I can do it differently. For the contemporary writers, almost always they’ve found me, one way or another. With the case of Xi Chuan, it happened like this: I met him briefly in the fall of 2007, and then a few months later I got an email, almost out of the blue, from Eliot Weinberger, recommending that I send a proposal to New Directions to translate Xi Chuan’s poetry. I wrote to Xi Chuan, he agreed, and the rest almost took care of itself!

What has been the most rewarding aspect of translating Xi Chuan’s poetry?

A million rewards, one of which is simply getting to know him. He’s really one of the best people around, one of the smartest and most interesting and also most generous. At a more literary level, I’d say that the most rewarding thing has been having my developing aesthetic shaped through the process of translating his poetry. Translating his poetry I get to see how he’s working right up close, which has meant that my standards as a reader of the work of others have become all the more exacting.

Do you have any advice for readers new to Xi Chuan about where best to begin or how to approach his poetry?

My advice to new readers of Xi Chuan would be different depending on what those readers are used to reading, because he made a pretty big stylistic change in the early nineties. If you like well-crafted lyrical poems, calm and deep, then start with his earliest publications at the beginning of Notes on the Mosquito and work your way through the whole book. If you like more expansive prose poems, long sequences, and the poetics of knowledge with a good sense of humor, then maybe skip Xi Chuan’s earliest work and start with his prose poetry—or what he calls “poessays”—coming back to his earlier lyrics later.

You are a writer and academic as well as a translator—how do these roles interact with each other?

I call myself a writer to the extent that I treat writing as an important aspect of my work (alongside reading and teaching), the part of my work that I spend the most time working on (I don’t spend anywhere near as much time trying to improve my reading or my teaching as I do my writing). Even or especially when translating and writing academic papers, I think of writing as a craft, as what my friend the poet and translator Eleanor Goodman calls “working with words.” So while I do write poems from time to time, I haven’t published much—far too little to call myself a poet (translating poets like Xi Chuan has also made me have very high standards for my own work). At any rate, I feel like I can make a better contribution to the world of poetry in English as a translator than I can as a poet.

So how does my work as an academic interact with my role as a translator? Well, on the one hand, being an academic means I have a steady salary, so I can afford to be selective about the translation projects I take on. If I’m translating something, it’s because I really want to translate it. At the same time, my field of scholarship is translation and Chinese literature, and I’m not only interested in finding new ways to bring my academic understanding of certain texts or writers to my work as a translator, but in finding new ways to bring translation as an area of inquiry into my academic work on Chinese poetry and poetics, as well. I learn a lot from translating, and I love having the opportunity to explore what I’ve learned at a deep intellectual level.

If one of your students told you they wanted to be a literary translator after graduation, what advice would you give them?

Do it. Find a way to make it work. Also: read a lot in the target language.

Can you tell us anything about what you’re working on at the moment?

I’ve just published October Dedications (Zephyr / Chinese University Press), a book of poems by Mang Ke, one of the seminal figures in the creation of contemporary Chinese poetry; and I also have about twenty translations of late Tang dynasty poet Li Shangyin in an eponymous book published by New York Review Books and edited by Chloe Garcia Roberts. And my academic monograph, The Organization of Distance: Poetry, Translation, Chineseness (Brill), came out a couple months ago, too.

As for in-progress, I’m in the middle of translating the New & Selected Poems of Duo Duo, one of the most influential contemporary poets in China—from when contemporary Chinese poetry was reborn in the seventies, from when the whole of society liberalized in the eighties, from when he lived in exile in the Netherlands in the nineties, and since his return to China in 2004. He’s been translated into English before (stylistically quite differently from how I approach his work), but he hasn’t had a book of poems in English since 2002. I plan on including just about everything he’s published in Chinese since then, and then offering a new selection of his output since his earliest pieces in 1972. But to do that, I’m translating it all—all the poems he has published since then—so that I can be sure what works in English. It’s pretty incredible work (and very different from Xi Chuan)!

Thank you for taking the time to answer our questions, Lucas!

And you can find more interviews in our Talking Translation series here.